China lock-down seals off Tibetan unrest

- Published

In the past week alone, five people have set themselves on fire, in a campaign calling for more freedom for Tibetans

From the air, the snow-capped mountains of China's Sichuan province push through the clouds in dramatic formations.

But it is not easy to see them from the ground: most are in Tibetan areas that are now being closely monitored following unrest.

On the road to Kangding - a gateway to this Tibetan world - China's public security bureau has set up at least one 24-hour roadblock.

Officers wearing protective clothing stop and search vehicles for "dangerous" items, and check the papers of those wanting to travel beyond.

Foreigners - particularly journalists - are not allowed through.

Many of Sichuan's Tibetan areas are in ferment. Monks have set themselves alight and citizens have staged protests against Chinese rule.

Beijing's national leaders blame outside forces - particularly the Tibetans' exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama - for stirring up trouble.

But it is difficult to find out exactly what is going on. On a journey into Tibetan areas the BBC was turned back, detained and hassled by China's security forces.

'Mob' protest

China's leaders and the Tibetans they govern have had a strained relationship over recent decades.

It dates back to at least 1950 when Chinese troops marched into the Himalayan region and re-established Beijing's control over an area that had been largely left to govern itself until then.

There were riots and protests across Tibet - and in other provinces where Tibetans live - four years ago.

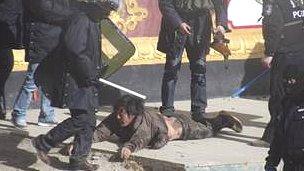

Campaign group Free Tibet says this photo shows recent protests in Sichuan province

One area that saw violence in that outbreak was western Sichuan, a mountainous area with a large Tibetan population.

Trouble flared here again early last year when monks began to set fire to themselves as a form of protest against what they see as political and religious represssion.

A total of at least 20 Tibetans - most of them monks and nuns - are thought to have self-immolated since then.

Two weeks ago, during the Chinese New Year holiday, angry Tibetans - the Chinese government called them a "mob" - staged protests in several towns. At least two Tibetans were killed.

There is now an extensive security operation in western Sichuan.

At the roadblock on the way to Kangding, just outside the city of Ya'an, dozens of security personnel carry out thorough checks.

Officers board buses and force car passengers out of their vehicles while they check glove compartments and boots for dangerous items.

Millions of visitors

A BBC team was stopped and held at the roadblock. "Foreigners are not allowed into Tibetan areas," said one security man.

We were then escorted back into Ya'an, where we were questioned at government offices by an official, surnamed Ma, who veered from friendly to threatening.

"You need to make a confession and sign a statement saying you will not go back into Tibetan areas," he barked at one point.

We refused and were eventually released - nine hours after first being detained.

Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, is also on alert.

The measures adopted in Tibet would no doubt be recognised by China's early communist leaders

Armed police officers patrol the area to the south of Wuhou Temple, a network of streets that serves as the city's Tibetan quarter.

Police vehicles, with their blue lights flashing, are parked on street corners.

Chengdu travel agents say foreigners are not allowed to buy tickets for many destinations in western Sichuan.

Only a single Tibetan area remained open to non-Chinese people, said one tour operator - a mountainous area to the north that contains a famous tourist spot, Jiuzhaigou national park.

Tibetan villages dot the valleys and hillsides of this beautiful area, which receives millions of visitors every year.

Tibetans here are richer than elsewhere, partly because of the money brought in by visitors. Many work in the tourist industry.

Forced denunciation

One of them is Liu Xiaobing - half Tibetan, half Han Chinese - who drives a taxi. His wife still carries out a traditional occupation, herding yaks and goats.

Mr Liu and his family have just moved into a new spacious home in a valley - their old one was up a mountain - near the entrance to the national park.

"It's harmonious here. We want peace - just like everyone does," he said.

But it is not harmonious over the mountains to the west of Jiuzhaigou.

In recent demonstrations against Chinese rule in Seda county, the authorities admitted that they had opened fire on protesters.

A few days ago, three Tibetans set themselves alight in the same area, continuing the recent tradition of gruesome personal protests.

Robert Barnett, of New York's Columbia University, said this region of western Sichuan, historically known to Tibetans as Kham, was relatively peaceful until a few years ago.

"We are talking about an area where China had a working relationship with Tibetans," said Mr Barnett.

But he said trust started to disappear just over a decade ago when the central government began introducing hardline policies that were already in place in Tibet proper.

One of those requires Tibetan monks and nuns to complete a period of "patriotic education", at the end of which they are forced to denounce the Dalai Lama.

"The Dalai Lama told them they should do it, that it didn't matter - but of course is does matter if you're religious," said Mr Barnett.

Many Tibetans complain that their culture, language and way of life are being eroded by policies initiated in Beijing.

By contrast, China's leaders believe they are bringing development and modernisation to backward Tibetan areas. "The Tibetans here earn more than I do," said one senior Jiuzhaigou official, surnamed Zhou.

His claim might be true, but Mr Zhou did not want the BBC checking it out by actually speaking to any Tibetans. We were followed, and once more detained for questioning.

Across Tibetan areas of western Sichuan, China has poured in security forces, cut communications with the outside world and tried to prevent foreigners from getting in.

That does not seem like the actions of a government that is confident about how it administers its Tibetan areas.

- Published16 November 2011

- Published7 November 2011