Can China's ivory trade ban save elephants?

- Published

Ivory is highly prized in China, where items can sell for thousands of dollars

There was a time when Liu Fenghai had 25 craftsmen working exclusively on elephant ivory at his factory in the northern city of Harbin.

He would buy the raw ivory and then have it turned into the pendants, paperweights and statues that once filled shelf after shelf in his shop, as well as the much larger, elaborately carved whole tusks proudly displayed on plinths of their own.

At the height of the market some of them could sell for many thousands of dollars.

Now, to the delight of conservationists everywhere, China is calling a halt to this legal, state-sanctioned trade.

But Mr Liu, as you might expect, is far from happy. "I feel sad," the 48-year-old said. "I don't feel good at all. This tradition has been carried on for thousands of years but now it will die in the hands of our generation."

"I feel like a sinner," he added. "In a few hundred years time, we will be seen as the sinners of history."

Mr Liu says he will mourn the end of the legal ivory trade in China

In fact, although ivory carving can indeed be traced back centuries in China, for much of that time it existed only as a niche art form and the Chinese made barely a dent in the global ivory trade.

Throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries, the mass slaughter of elephants was carried out at the hands of the European colonial powers and then later North American entrepreneurs.

Western demand for ivory ornaments, jewellery, piano keys and billiard balls helped reduce the African elephant population from more than 20 million in the year 1800 to just two million by 1960.

Then came Japan's post-war economic rise and the slaughter was propelled through the 1970s and '80s, by which time the elephant was teetering on the brink of extinction.

It was only with the international ban on the trading of elephant ivory in 1989 that the species was given a brief respite.

Once again though, it was another major shift in the global financial order that signalled further disaster - China's emergence as a major economic power.

An explosion of wealth coupled with the Communist Party's unique blend of corruption and crony capitalism made ivory the perfect repository of value, both for ostentatious displays of success and discrete gift giving.

The facts and figures behind China's ivory trade

An art form became an industry and in a few short years China began to account for up to 70% of the global demand, external for ivory.

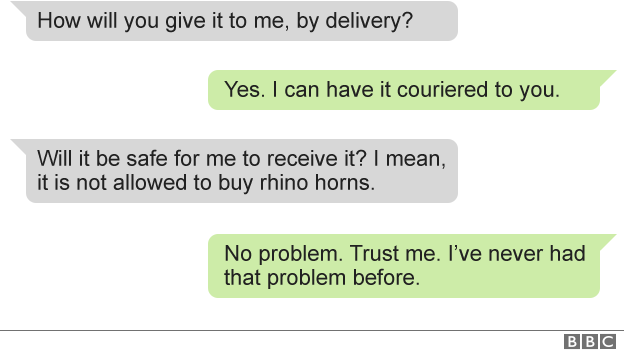

Today, as a result of the surge in poaching, the elephant is once again facing complete annihilation, with estimates suggesting there are fewer than half a million left, external in Africa.

There may be no more wild populations within a decade.

If Mr Liu believes it is a sin to lose an ancient art, how much more of a sin to lose an ancient species in the name of the mass-produced - often machine-carved - ivory tat that makes up the bulk of the products on sale in China today?

Not a moment too soon, the Chinese government has decided which side of history it wants to be on.

A 'game changer'

This week, by the end of business hours on Friday, almost half of China's authorised, government-approved ivory factories and shops will have closed their doors for good.

A team of officials from the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites) will be on hand to witness the shutdown.

The rest of China's legal trade will be gone by the end of the year - a total of 34 factories and 138 shops.

You might also be interested in these stories:

'You may as well kill us': Human cost of India's meat 'ban'

Vegetable ivory: Could an obscure seed save the elephant?

'Nothing short of miraculous': Rare tigers found in eastern Thailand

It is a deeply symbolic moment, a "game changer" according to campaigners, with one of the most high profile and vocal, the UK's Prince William, publically applauding the Chinese government's decision as "an important commitment".

No small irony, perhaps, given the role the prince's own ancestors played in promoting the trade, with more than 1,000 ivory items still held in the royal collection.

China's move could put pressure on other markets where ivory is traded, like Hong Kong

Estimates suggest poaching has reduced the African elephant population to less than half a million

Campaigners say China's move could be a "game-changer" for elephants

But closing China's carving workshops and retail outlets is so important, it is argued, not only for its own sake, but because this legal business acts as cover for a much bigger black market trade.

In 2008 China was allowed, under the Cites system, to buy a 62-tonne stockpile of African ivory.

The theory was that, with careful monitoring and a system of certificates, the stockpile would provide a controlled supply to China's factories and therefore dampen demand for illegal ivory by helping to keep prices low.

It has had the opposite effect. It appears to have in fact stimulated demand by giving consumers the green light that ivory was ok to buy. Coupled with poor enforcement, corruption and fraudulent certifications a huge amount of illegal, newly poached ivory flooded into China and on to the market, some of it under the guise of Cites authorised stock, external.

Demand rose further and prices, rather than going down, skyrocketed. Research suggests that the illegal stockpile of ivory in China today may stand at 1,000 tonnes or more, external, far in excess of that supposedly well regulated and controlled quantity purchased back in 2008.

Now, although there are undoubtedly other factors at play - not least the slowing Chinese economy and the crackdown on official graft and gift giving - the announcement of the ban on the legal trade does appear to be helping to bring the speculative frenzy to an end.

Consumers and dealers have been sent a strong signal that the game is up and prices of ivory have recently been dropping, from more than $2,000 (£1,611) per kg in 2014 to around $700 per kilo today.

Despite ivory seizures around the world, like this one in Thailand, smuggling persists

Big questions remain, however. As in other markets, like the UK, the Chinese announcement appears to allow for the continued trading of antiques, which campaigners fear may act as a loophole.

Meanwhile, the government has not said what it will do with the remaining stockpile of legal ivory and how it will prevent it from leaking on to the black market.

And while the new policy may well drive the illegal trade further underground, controlling it will still depend on the resources given to law enforcement agencies.

Our own research suggests a less than wholehearted willingness to tackle wildlife crime.

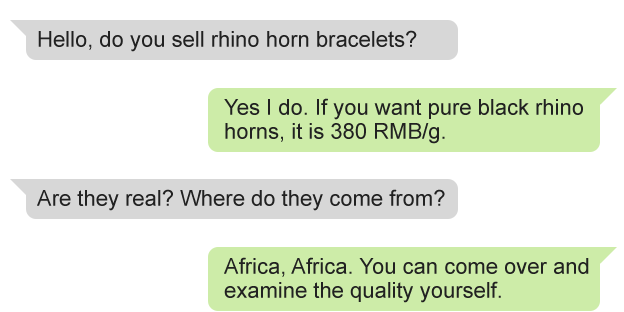

For more than two decades, trade in rhino horn has been completely prohibited in China. Selling, purchasing, transporting or mailing it has been punishable by harsh sentences, including life imprisonment for the worst offenders.

And yet, via a quick search on the internet, traders can be found openly offering rhino horn for sale as whole pieces, as jewellery or for use in Chinese medicine.

The risk attached to both buying and selling appears to be small.

"Trust me, I've never had any problems before," one of the online vendors said, after sending us pictures of rhino horn bracelets.

Exchange between the BBC and an online rhino horn trader

But now, after decades of defending ivory carving as an intangible cultural asset, the Chinese government is finally turning its back on it.

It has decided that the diplomatic advantage in joining the growing international consensus far outweighs the relatively small economic value of the industry.

Its decision will put pressure on other jurisdictions that continue to allow a regulated, domestic ivory trade to do more, most notably Japan and Hong Kong, but perhaps also countries like the UK.

But, however significant, no one believes China's decision will bring an end to elephant poaching.

That goal will only be accomplished when there is a shift in the attitude of consumers in China and other countries where the demand remains high.

And while there is promising evidence to show that public information campaigns are working, external, it will take time.

In his office above his ivory shop in Harbin, complete with a footstool made from a severed elephant leg, I ask Mr Liu if he agrees that elephants are more beautiful alive than dead.

"I don't agree," he says. "Ivory is the best material for carving art. Even if it is as small as a grain of rice, you can carve a poem on it."

"You cannot say an elephant is beautiful but a piece of ivory is not."

- Published30 December 2016

- Published31 August 2016

- Published2 October 2016

- Published25 September 2016

- Published26 February 2015

- Published29 April 2016