Hong Kong protests: Leader Carrie Lam defiant on extradition plan

- Published

Critics say the plan will erode the city's judicial independence

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam has said she will not scrap a controversial plan to allow extradition to mainland China, despite mass protests.

On Sunday, hundreds of thousands of people rallied against the bill which critics fear allows China to target political opponents in the region.

Speaking to reporters on Monday, she insisted the law was necessary and said human rights safeguards were in place.

Chinese state media said "foreign forces" were behind the protests.

Organisers estimate that one million people took part in Sunday's march, although police put the figure at 240,000 at its peak.

If the organisers' estimate is confirmed as correct, it would be the largest demonstration in Hong Kong since the territory was handed over to China by the British in 1997.

After Sunday's protests tapered off, violence broke out between protesters and police. At least three officers and a journalist were injured.

Another rally will be held on Wednesday, when the second reading of the bill will be debated by legislators, the AFP news agency quoted protest organiser Jimmy Sham as saying.

What did Hong Kong's chief executive say?

Carrie Lam said in a press conference on Monday the law would in no way erode any of the special freedoms the territory enjoys.

"The bill wasn't initiated by the central people's government," Ms Lam said, referring to Beijing. She said the law was proposed out of "conscience" and "commitment to Hong Kong".

Despite the protests, Ms Lam refused to scrap the bill

She also promised legally binding human rights safeguards, and regular reports of implementation of the bill to the legislature.

Clashes followed the mass protest over the extradition plan

The march was seen as a major rebuke of Ms Lam, who has pushed for the amendments to be passed before July.

Critics of the bill say it will expose Hong Kong residents to China's deeply flawed justice system, and lead to further erosion of judicial independence.

Supporters say safeguards are in place to prevent anyone facing religious or political persecution from being extradited to mainland China.

Tough battle for the 'good fighter'

By Grace Tsoi, BBC News, Hong Kong

Whichever number you believe, this was a huge protest by Hong Kong's standards and this controversial bill has prompted opposition from the most unexpected corners of society.

Two years ago, Carrie Lam ran on a manifesto of "We Connect", vowing to unite a deeply split society after the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014. She was never the most popular candidate running to be Hong Kong's leader and won largely because of Beijing's blessing.

She has always been considered a capable, experienced bureaucrat who is deft at tackling thorny issues - her moniker is "good fighter". But critics say the first female leader is arrogant, elitist and unwilling to listen to the people.

The banners out on Sunday - many with her face emblazoned on - are an indication of just how personal this protest has become.

Isn't Hong Kong under Chinese rule anyway?

Hong Kong was a British colony from 1841 until sovereignty was returned to China in 1997.

Central to the handover was the agreement of the Basic Law, a mini constitution that gives Hong Kong broad autonomy, external and sets out certain rights.

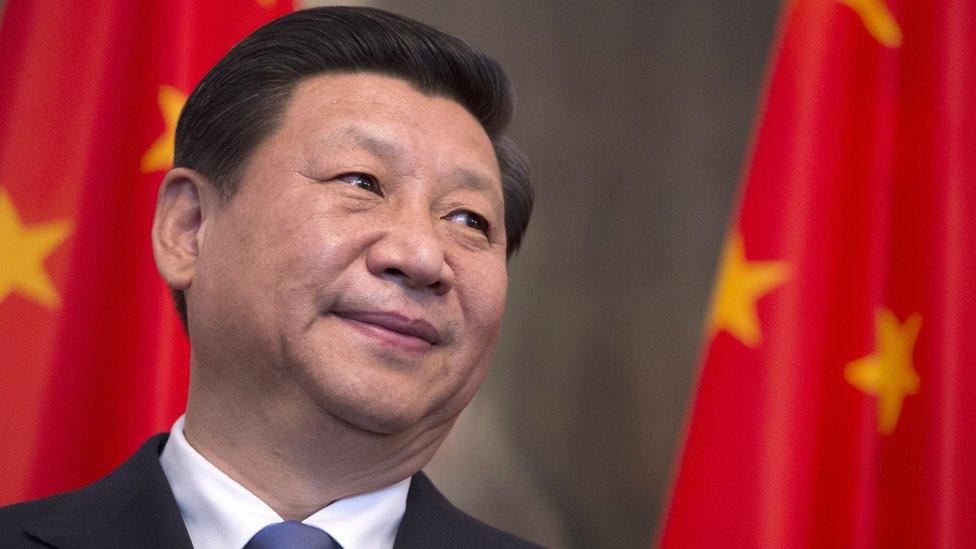

Under Xi Jinping, critics say, Beijing is seeking to increase influence over Hong Kong

Under the so-called "one country, two systems" principle, Hong Kong has kept its judicial independence, its own legislature, its economic system and the Hong Kong dollar.

Its residents were also granted protection of certain human rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech and assembly.

Beijing retains control of foreign and defence affairs, and visas or permits are required for travel between Hong Kong and the mainland.

However, the Basic Law expires in 2047 and what happens to Hong Kong's autonomy after that is unclear.

What has the mainland said?

The protests were strongly criticised in an editorial on Monday in the state-run newspaper China Daily, which argued that "some Hong Kong residents have been hoodwinked by the opposition camp and their foreign allies into supporting the anti-extradition campaign".

The paper argued that "any fair-minded person" would support the "long overdue" bill meant "to plug legal loopholes and prevent Hong Kong from becoming a safe haven for criminals".

Foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said on Monday that Beijing would "continue to firmly support" Hong Kong's government, adding: "We firmly oppose any outside interference in the legislative affairs" of the region.

Reports about Sunday's protests were heavily censored in mainland China, with international media blocked and searches on social media directed to pro-Beijing publications in Hong Kong.

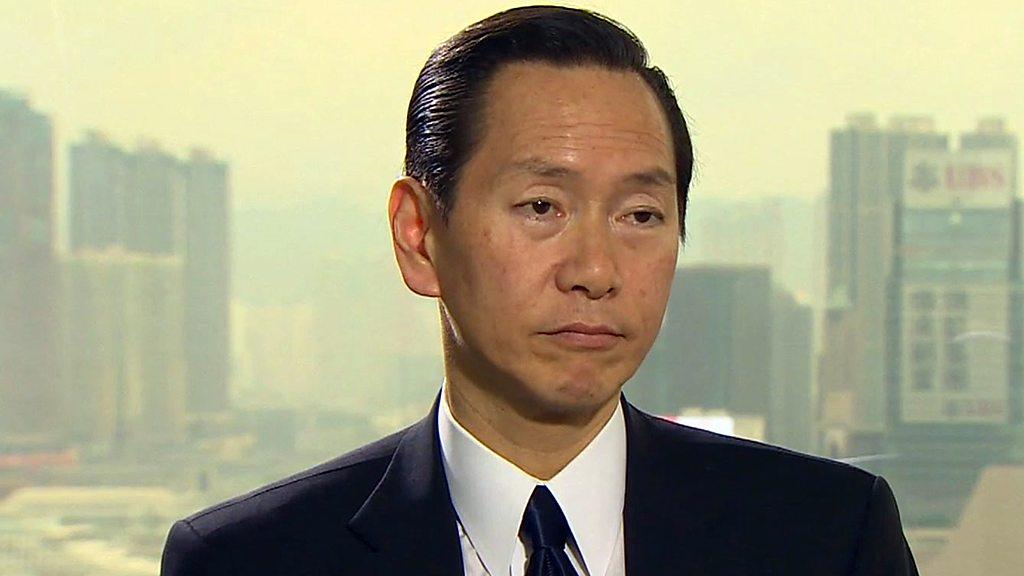

State media frequently blame protests in Hong Kong on foreign forces as a way to discredit protesters, Prof Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute, told the BBC.

What are the proposed changes?

They allow for extradition requests from authorities in mainland China, Taiwan and Macau for suspects accused of criminal wrongdoing such as murder and rape. The requests will then be decided on a case-by-case basis.

The move came after a 19-year-old Hong Kong man allegedly murdered his 20-year-old pregnant girlfriend while they were holidaying in Taiwan together in February last year.

The man fled to Hong Kong and could not be extradited to Taiwan because no extradition treaty exists between the two.

Hundreds of thousands of people joined the march

Hong Kong officials have said Hong Kong courts will have the final say over whether to grant extradition requests, and suspects accused of political and religious crimes will not be extradited.

But critics say people would be subject to arbitrary detention, unfair trial and torture under China's judicial system.

"It could give China additional leverage to counteract Western policies against its interests... Once this law is passed, Beijing could extradite foreigners staying in or passing through Hong Kong," Prof Dixon Sing, a social scientist from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, told the BBC.

Opposition against the law is widespread across Hong Kong, with groups from all sections of society - ranging from lawyers to schools to house wives - having voiced their criticism or started petitions against the changes.

The government has sought to reassure the public with some concessions, including promising to only hand over fugitives for offences carrying maximum sentences of at least seven years.

Hong Kong has entered into extradition agreements with 20 countries, including the UK and the US.

- Published10 June 2019

- Published9 June 2019

- Published13 December 2019

- Published1 April 2019

- Published19 November 2018

- Published14 August 2018