Hong Kong extradition protests: Do China demonstrations ever work?

- Published

Critics say the plan will erode the city's judicial independence

Organisers say more than a million people - one seventh of Hong Kong's population - took part in Sunday's demonstration against a planned bill to allow extradition to mainland China.

It was one of Hong Kong's largest ever protests, and the biggest since the former British colony was handed back to mainland China in 1997.

But Hong Kong's leader Carrie Lam - who was elected by a mostly pro-Beijing panel of 1,200 people - has vowed to press ahead with plans to pass the law.

So do protests in Hong Kong - which has certain freedoms, but not full democracy - ever work?

And what are the odds of protesters succeeding this time?

Why do people in Hong Kong protest?

Public protests play an important role in Hong Kong - as one local journalist has put it, for many demonstrators, protesting is "in their DNA", external.

Since Hong Kongers have the right to protest, but cannot directly elect their government, many see taking to the streets as their way of forcing change - especially with issues they see as threatening the territory's core values.

"It might be futile," one of Sunday's protesters, April Ho-Tsing, 27, told the BBC.

"But we have to act and show the Hong Kong government, the international press, other Hong Kongers - that we won't just roll over and let the Chinese government walk all over us."

And some protests have led to unexpected - and dramatic - wins in the past.

Sunday's protest was one of the biggest in Hong Kong history

In 2003, an estimated 500,000 people took to the streets against a controversial national security bill known as Article 23 - and the government was eventually forced to shelve it.

But experts think protests are much less likely to work this time because the current leadership in Beijing is unlikely to compromise.

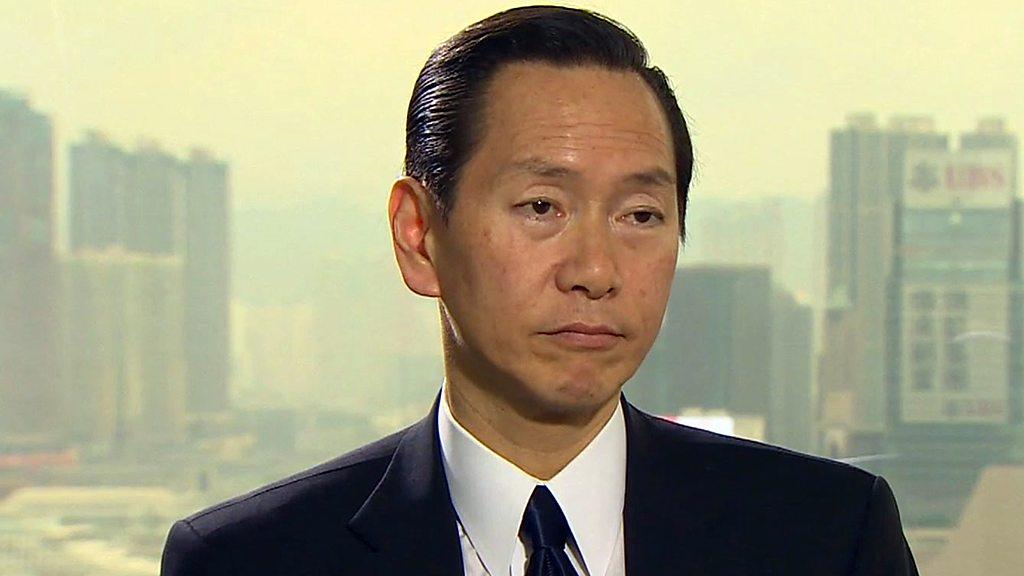

"One major change has been that China's leader, Xi Jinping, has pursued a much harder stance than his predecessor," says Prof Dixon Sing, a social scientist at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

"The second related change has been that China's economy has become much stronger than it was in 2003."

Prof Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at SOAS, agrees that "the odds are very much against the protesters in Hong Kong" this time.

"Under Hu Jintao [Mr Xi's predecessor] you had a central leadership that's much more willing to allow local leaderships to deal with things their way - whereas Xi is focused a lot more on strengthening party leadership and discipline.

"There's a very clear position under Xi Jinping that China will not tolerate any activities that could potentially destabilise the rule of the Communist Party."

This was also reflected in the 2014 "Umbrella" protests - where tens of thousands of people camped in the streets for weeks to demand fully democratic elections.

Despite being mostly peaceful - and making headlines around the world - the protests failed to achieve any concessions from Beijing.

A number of the protest organisers have since been given jail terms on public nuisance charges.

What's the situation in mainland China?

Despite not being formally allowed by law, tens of thousands of protests - mostly on local or environmental issues - actually take place each year.

Many protesters and petitioners get arrested but, perhaps surprisingly, some protests have also forced local governments to back down.

One notable example was in 2011, when the government in Dalian agreed to close a chemical plant after 12,000 people demonstrated against it.

Demonstrators feared that paraxylene (PX), a chemical that can be highly toxic, would pollute the environment

"Some very specific not-in-my-backyard-type protests have resulted in concessions by the authorities," says Prof Tsang, adding that these are seen as "easier to accommodate" because they focus on local issues rather than political ones.

However, he says this has also reduced in recent years as the Communist Party has tightened its control centrally.

Prof Tsang says many "local governments simply don't take risks any longer - why do anything to risk the disapproval of Beijing?"

Is there any chance the extradition bill will be stopped?

Clashes erupted at night after a mostly peaceful march during the day

Experts say it's technically possible, but unlikely.

To become law, the bill needs to be approved by Hong Kong's legislative council where some, but not all, of the seats are directly elected by Hong Kong's voters, and where pro-government groups have a majority.

After the major protests in 2003, the government made major concessions to the national security bill - but still intended to push it through the legislative council.

It was forced to make a last-minute U-turn after the pro-business Liberal Party decided to withdraw its support.

As a result, this time, "it's a question of whether any of the middle-of-the ground political parties decide to switch sides," says Prof Tsang.

However, he considers this unlikely, especially since the political environment in Hong Kong and China has changed.

"There are more die-hard pro-Beijing parties" in the legislative council now, says Prof Sing, "and they have a nearly zero chance of reversing their stance."

- Published9 June 2019

- Published13 December 2019

- Published1 April 2019