India election: Is there a surge of support for Narendra Modi?

- Published

Narendra Modi is the main opposition BJP's prime ministerial candidate

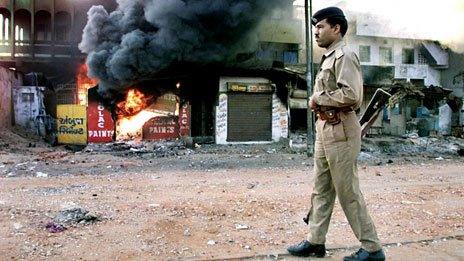

Since early 2013 one question has dominated Indian political discourse: will there be a "wave of support" for Narendra Modi of the main opposition BJP? The Gujarat chief minister has an impressive economic record, but has been seen as divisive since deadly religious riots in the state in 2002. He currently looks like the man to beat, according to political scientist Milan Vaishnav.

When Mr Modi was named the Bharatiya Janata Party's (BJP) prime ministerial candidate in September, it was too early to tell whether Indians were prepared to vote in large numbers for him.

Following the BJP's triumph in state elections in December, there were signs something was afoot.

Now, with the recent release of three pre-election surveys, the evidence of "a wave" is incontrovertible. Notwithstanding this, the gauntlet of Indian politics rarely permits cakewalks.

Complex

There are four key pieces of evidence in support of this unusual surge behind Mr Modi, drawn from a recent survey conducted by the Delhi-based Lokniti, external programme of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), a respected Indian think tank.

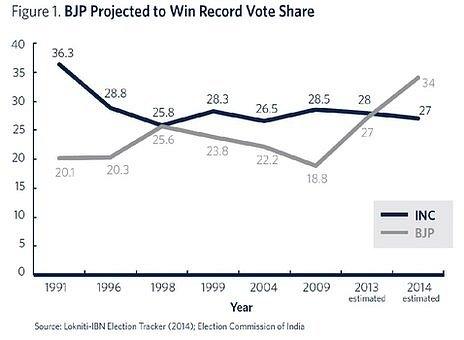

First, the BJP garnered 18.8% of votes in 2009, a steady decline from its all-time high of 25.6% in 1998 (see figure below).

In a CSDS July 2013 survey, the BJP was projected to win 27% of votes. This number had grown to 34% in January 2014 - an 80% rise from 2009.

Given the vagaries of India's winner-take-all election system, converting votes into seats is complex.

Estimates suggest 34% of the vote would translate to between 192 and 201 of 543 parliamentary seats - a steep increase from its 2009 tally of 116 seats.

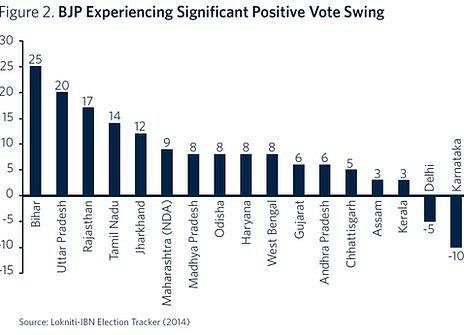

Second, according to CSDS, there is a huge pro-BJP vote swing under way in the electorally pivotal states in the north Indian "Hindi heartland", external (see figure below).

In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, which together account for 120 seats, the BJP is enjoying increases of 25 and 20 percentage points in its vote share, respectively.

What is unusual about these states is that they do not feature head-to-head contests between the Congress and the BJP; instead, each of these states boasts formidable regional parties.

This means that the shift toward the BJP goes beyond simple anti-Congress party sentiment.

In Uttar Pradesh, disaffection with the Congress is not simply benefitting the state's major regional players - the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party - but rather the BJP.

In Bihar, voters would like to see the ruling Janata Dal (United) government remain at the state level, but are flocking toward the BJP when it comes to parliamentary elections.

Moreover, the BJP is expected to poll unusually well in states where it historically has not.

Popularity

This is not due to a suddenly robust party organisation, but the apparent popularity of a Modi candidacy.

Indeed, the party has had little traction over the last several elections in southern India, save for the state of Karnataka.

Yet in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the BJP's vote share has grown by 6 and 14 percentage points, respectively, albeit from a low base.

The BJP's projected performance is probably not enough to win seats, but is indicative of swelling support.

Moreover, if the upward trend persists, other regional parties may join hands with the BJP ahead of elections.

Third, Mr Modi's impact is evident in voters' preferences (see figure below).

.jpg)

In 2009, 2% of voters favoured Mr Modi.

That number has steadily grown to 5% in 2011, 19% in 2013 and 34% as of January 2014; comparing favourably to the stagnant support for Congress party vice-president Rahul Gandhi.

In virtually every state where the CSDS conducted its survey, voters preferred Mr Modi over Mr Gandhi.

In October, 31% of voters in Madhya Pradesh wanted to see Mr Modi become prime minister. Today, 54% do.

In Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, 15% and 40% of voters preferred Mr Modi just months ago. Now, 28% and 48% of voters do.

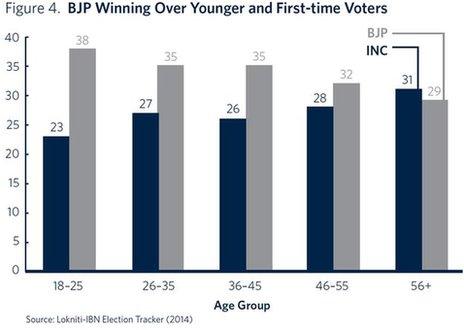

A fourth sign of a Modi wave of support is the BJP's noticeable appeal to younger voters.

His relentless talk of growth, jobs and development - not to mention his economic credentials in Gujarat - seeks to capitalise on the aspirations of a population with a median age of 25.

Different conditions

The BJP is by far the preferred party of voters between the ages of 18 and 25, though its appeal declines as voters get older (see figure below).

Nevertheless, the only age group where the Congress trumps the BJP is 56 years and above.

It is true that surveys incorrectly predicted BJP wins in 2004 and 2009, but the conditions today are different.

For starters, there is palpable resentment over slow growth, high inflation and the lack of employment.

Moreover, there are indications that many Indians are hungry for decisive leadership, a quality missing under the prevailing government, but attributed to Mr Modi.

Even if the surveys are accurate, other obstacles to Mr Modi's ascension loom.

Surveys say Mr Modi's support has grown ahead of the elections

These include nascent alliances between opposition parties seeking to blunt the BJP's popularity and tricky alliance mathematics.

A potential ally of the BJP, the AIADMK, recently announced an alliance with left-wing parties in Tamil Nadu, a veiled message by AIADMK leader J Jayalalitha, external that she is a contender in her own right.

Perhaps most worrying for Mr Modi is the rise of the anti-corruption, populist Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man party).

This party also targets young, urban, middle class voters, placing it in direct competition with the BJP.

With two months before voters cast their ballots, there is more than enough time for surprises.

The coast is not yet clear for the BJP, but it appears that they are indeed riding a "Modi wave".

Milan Vaishnav is an associate with the South Asia programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington DC. You can follow him on Twitter @MilanV.

- Published23 April 2024

- Published1 March 2012

- Published13 March 2012

- Published27 February 2012