The Hindu hardline RSS who see Modi as their own

- Published

The RSS has been banned thrice in post-Independence India

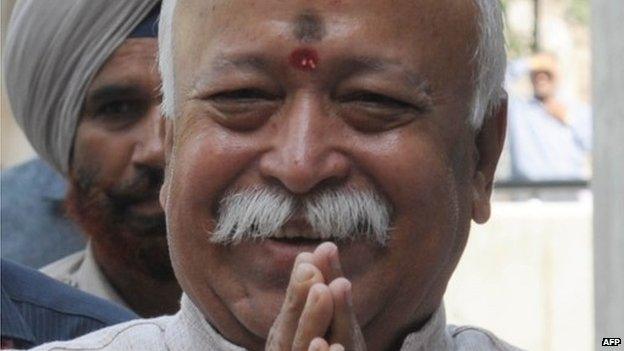

India's state-run TV channel Doordarshan recently had an unusual programme - it telecast live the annual speech of Mohan Bhagwat, the head of the right-wing Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteers' Organisation).

It's a group many believe to be a shadowy and violent Hindu organisation with umbilical ties to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Mr Bhagwat spoke, among other things, about the past glory of Hindu kings and supported the new government's initiatives.

It was the first time in the history of independent India that the ideological fountainhead of the BJP had been given such prominence in the state media.

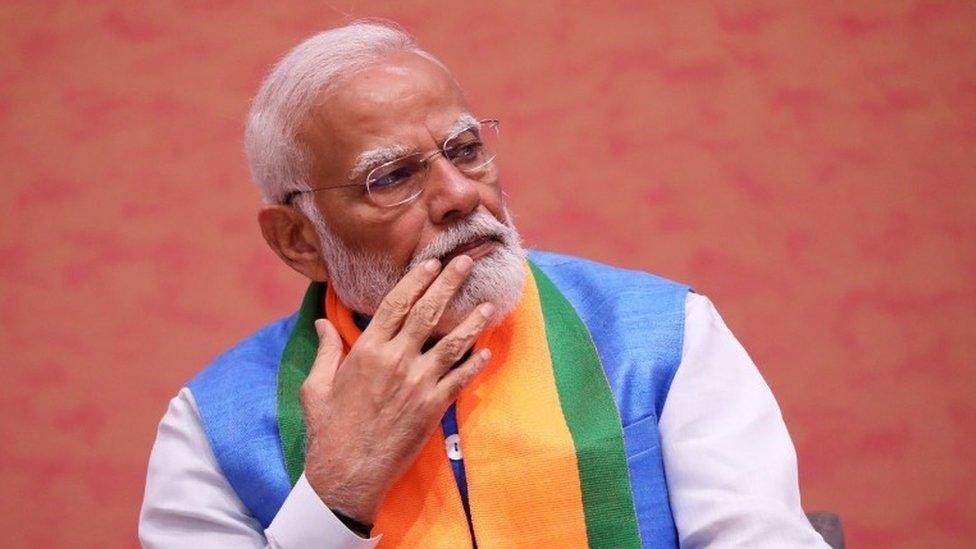

And considering India's new Prime Minister Narendra Modi was once a full-time RSS worker, the broadcast predictably created uproar among opposition parties and liberals.

The main opposition Congress and the Communist parties criticised the decision, accusing the government of being remote-controlled by the controversial organisation.

In response, Doordarshan said Mr Bhagwat's address had been covered as a news event and the government had nothing to do with the decision.

Controversial past

Established in 1925, the RSS (also known as the Sangh) has been banned three times in post-Independence India.

The first ban came after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948 - the organisation was accused of plotting the murder of the national icon but was later absolved.

It was a major setback to the image and credibility of the group which it took nearly three decades to shake off.

Mohan Bhagwat is the head of the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Shyamsevak Sangh

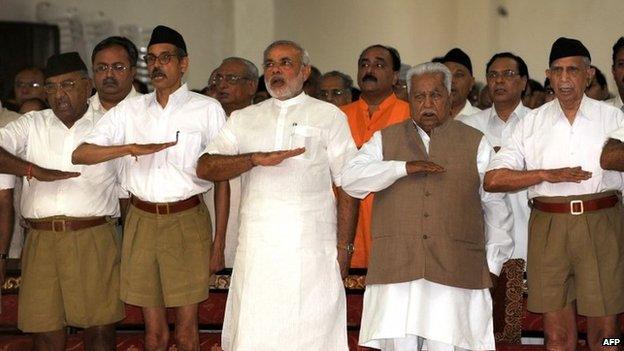

India's new Prime Minister Narendra Modi (centre) was once a full-time RSS worker

The group was once again banned in 1975 when then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi suspended all fundamental rights and jailed almost the entire opposition leadership.

The RSS used this opportunity to build alliances with anti-Congress forces and spread its political influence.

In the late 1980s, the RSS, through its affiliates, launched a massive movement to build a Hindu temple at the place of a medieval mosque in the northern town of Ayodhya.

The Babri Masjid (mosque) was demolished in December 1992 by supporters of radical Hindu groups, including the RSS. The group was outlawed for a third time but the courts overturned the decision.

Critics, however, say the organisation continues to be a sectarian, militant group, which believes in the "supremacy of Hindus" and "preaches hate" against Muslims and Christian minorities.

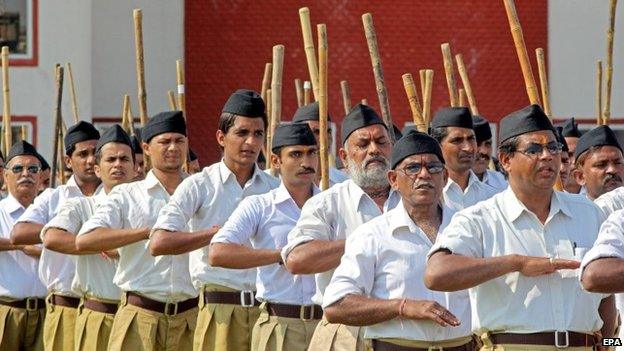

Clad in khaki shorts and white shirts, RSS cadres regularly gather in small groups in parks and street corners in different Indian cities and towns to work out, sing patriotic songs, play games and talk about the past glory of "Hindu India".

These groups are called shakhas (branches) and are the backbone of the organisation's countrywide network of committed workers. The Sangh claims to have shakhas in 50,000 villages and cities across the country, but it does not maintain a membership register.

According to the RSS website, "only Hindu males" can join the group. For women, there is a separate organisation called the Rashtra Sevika Samiti (National Women Volunteers' Committee).

The controversy around the broadcast of Mr Bhagwat's speech has led to a wider debate about the future relationship between the government and the RSS.

Will the Sangh be able to force the government to follow its agenda? Or, will a "tough leader" like Mr Modi allow this to happen? Or, will both work together towards the similar goal of establishing Hindutva (Hindu-ness) as an all-encompassing, superior political ideology in modern India?

Some commentators have also raised the question as to why a non-elected body, outside the multi-party democratic system, should be allowed to influence the government's decision-making process. So far, Mr Modi has not commented.

The questions are being asked against a backdrop of a bitter turf war that was fought out in the open between the RSS and BJP when the party was in power from 1998 to 2004.

Changed strategy?

But the situation has changed since then.

After the BJP lost the election to Congress in 2004, the RSS lost much of its clout. Commentators say the RSS has learnt the hard way that it needs a friendly government in Delhi if it wants to remain influential.

Political analyst Neeraja Chaudhary says the RSS showed great pragmatism by backing Mr Modi as the BJP's PM candidate in the 2014 elections over senior leaders like former deputy PM LK Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi.

Critics say the RSS is a sectarian, militant Hindu organisation

This, she says, despite the fact that as the chief minister of Gujarat, Mr Modi had sidelined the RSS leaders in the state.

"The RSS has taken a risk because Mr Modi will work on his own accord and may not necessarily take orders from the RSS," she says.

Senior journalist Ram Bahadur Rai, however, says there is "no rift between Mr Modi and the RSS".

Both Mr Rai and Ms Chaudhary agree that at the moment there is a clear understanding about the division of labour between Mr Modi and the RSS - that governance is the responsibility of the PM and that Mr Modi will ignore, within "acceptable limits", the Hindutva agenda being carried out at the grassroots level.

That, she explains, is the reason why Mr Modi keeps quiet when some of his party colleagues talk of "love jihad", accusing "Muslim boys of luring Hindu girls", or allege that "terrorism is taught in Muslim seminaries".

Ms Chaudhary says the RSS challenging Mr Modi is still a possibility sometime in the future, although "it is still premature to predict that situation because at the moment he is riding high".

"But pressure starts mounting the moment there is a decline in authority and acceptability of a leader."

It is probably then the pressure groups opposed to Mr Modi within the BJP and the RSS will think of making their move. But that situation, should it happen at all, is quite far away down the road.

- Published5 May 2014

- Published23 April 2024