India rupee crisis: The village with cash worth nothing

- Published

Rural India hit hard by currency ban

Indian banks are running out of replacement money after the government scrapped 86% of the cash in circulation last week. The BBC's Sanjoy Majumder travelled to northern Rajasthan to see how rural India, where cash accounts for almost all transactions, is coping.

It is 05:00 in Kirdola village, some 400km (250 miles) north-west of the Indian capital Delhi. Winter is setting in and there is a sharp chill in the air.

But very few people can be seen at the village square or the local teashop. The fields, which should be filled with farm labour at the onset of the sowing season, are empty.

Why India wiped out 86% of its cash

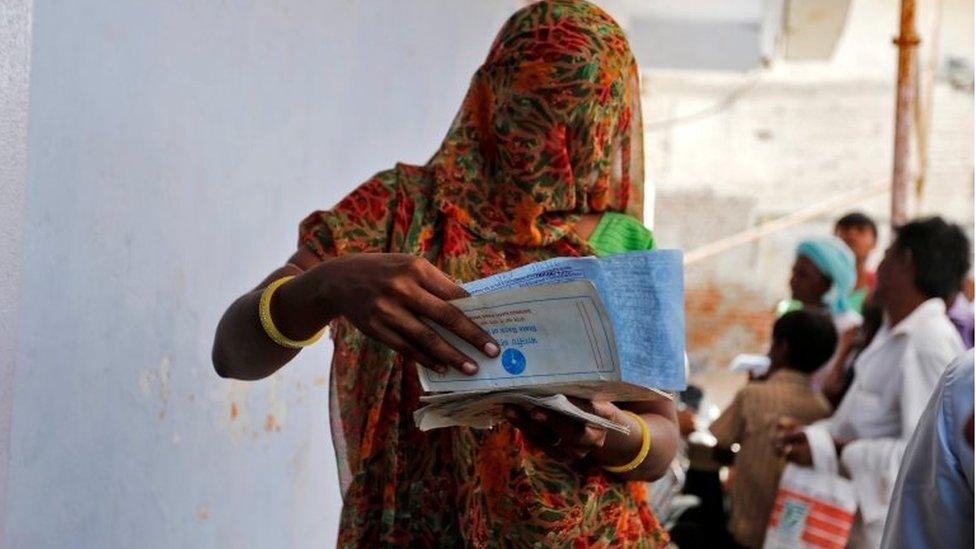

India's 'desperate housewives' scramble to change secret savings

How India's currency ban is hurting the poor

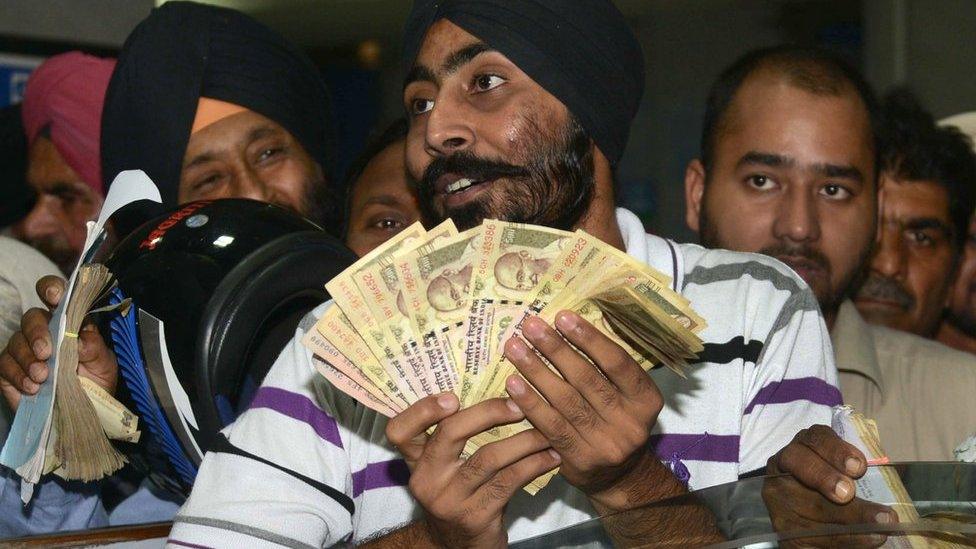

Instead, the action has shifted to the local branch of the Bank of Baroda where, already, there are about 50 people standing in a queue. Many of them are squatting on the ground, huddled together to stay warm, men on one side, women on the other. I join some people who have started a little bonfire.

Patience is running out in the villages

"It's been like this for the past few days," Nizam Khan tells me.

"The bank opens and then it runs out of money really quickly. There are some of us who have been coming here for four days."

Farm worker Jowara Ram is pacing up and down, looking extremely anxious.

The delay in getting out the new currency is causing massive distress in rural India

"It's my daughter's wedding tomorrow," he tells me, fishing out a beautifully illustrated invitation. "We have absolutely no money left at home. They told me to hand in my old notes, so I gave the bank everything, about 100,000 rupees ($1,475) that my whole family had."

He has been coming to the bank every day but every single time, cash ran out before it was his turn.

"That's why I've come so early. I've brought my wife, my daughter, my sisters - everyone's in the queue so that we can get some money out between us."

It's now 10:00 and there is a stirring in the crowd as a portly man gets off a scooter and makes his way through the throng to the cast iron sliding gates at the bank entrance.

He is the bank manager.

But as he unlocks the gate, he turns around and addresses the crowds: "Only deposits today. I have no cash to give out."

Villagers lining up outside the bank of Baroda in Kirdola

Long lines outside banks have become an everyday sight

He ducks into the bank hurriedly, as the crowd start shouting. I follow him in.

"What can I do?" the manager, JP Sharma, asks me. "We were promised money but it's not here. My bank serves five villages, they all need money but my hands are tied."

Jowara Ram is distraught. He cannot believe what he has just heard. He sinks to the ground with his head in his hands.

"What will I do now? I need money to buy food for the wedding guests and to pay for the ceremony. They will not take credit."

Cash crisis

Everyone is upset. One woman tells me that her kitchen is empty. "We have nothing to eat. I was hoping to buy some tea, sugar and flour to get by. Now what?"

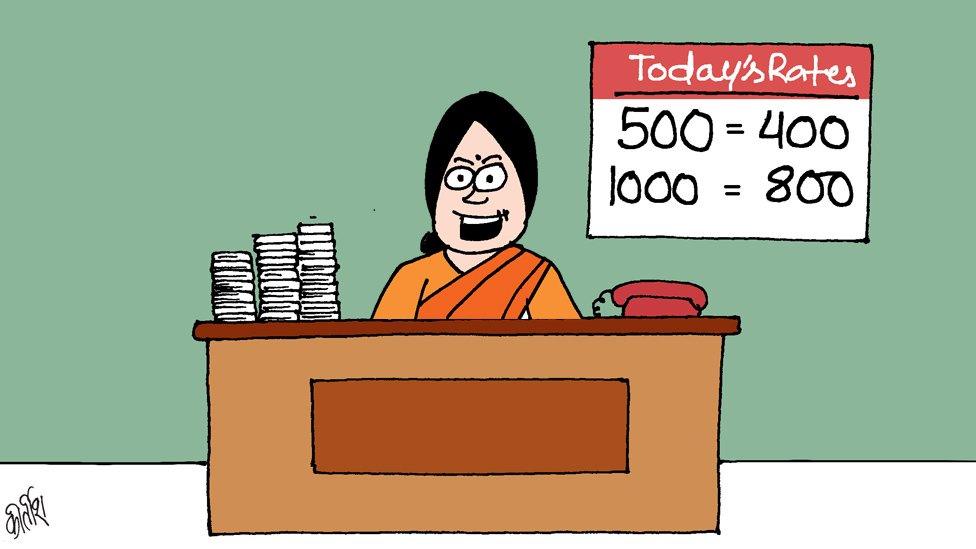

There is a lot of anger and bewilderment at the government's decision to take the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes out of circulation.

"Do you think we have black money [unaccounted cash] here?" asks Gajendra Singh, a farmer. "Farmers don't have to pay income tax in any case. So our cash is legal. We just keep it at home."

There are other, practical issues.

Mahesh Kumar has travelled 40km to come here, armed with 400,000 rupees ($5,895) in the banned notes. "There are 32 of us in my family. This money belongs to all of us."

But Mr Kumar, like the vast majority of rural Indians, does not have a bank account. And the bank has no time to open one for him.

There is anger and bewilderment at the government's decision

"What am I to do now?" he asks showing me a duffle bag stuffed with money. "They tell me this money is worthless. Does that mean our savings are wiped out?"

The impact of the currency crisis, however, goes beyond individual households.

It is hurting the entire rural economy.

Just behind the village are vast farmlands. Only a handful of farm workers are at work, painstakingly sowing onion seeds into the soil.

"This is an onion-growing area," local farmer Rameshwar Bagrodia explains. "It's labour intensive, you need hundreds of workers and this is the start of winter crop season. But no-one has any money to pay them."

It gets worse. The local livestock market, which normally does extensive trade, has ground to a halt - affecting suppliers, buyers and transporters.

"Even the milk that is locally produced has no takers. It's all going to waste," Mr Bagrodia says.

At the teashop, where most people have now gravitated to, the mood is dark.

"This had better end soon," one man mutters.

"Otherwise the mild protest you can see is going to turn violent."

- Published17 November 2016

- Published11 November 2016

- Published14 November 2016

- Published15 November 2016