What do the cash queues tell us about India?

- Published

Millions of Indians have been standing in queues to deposit or withdraw cash

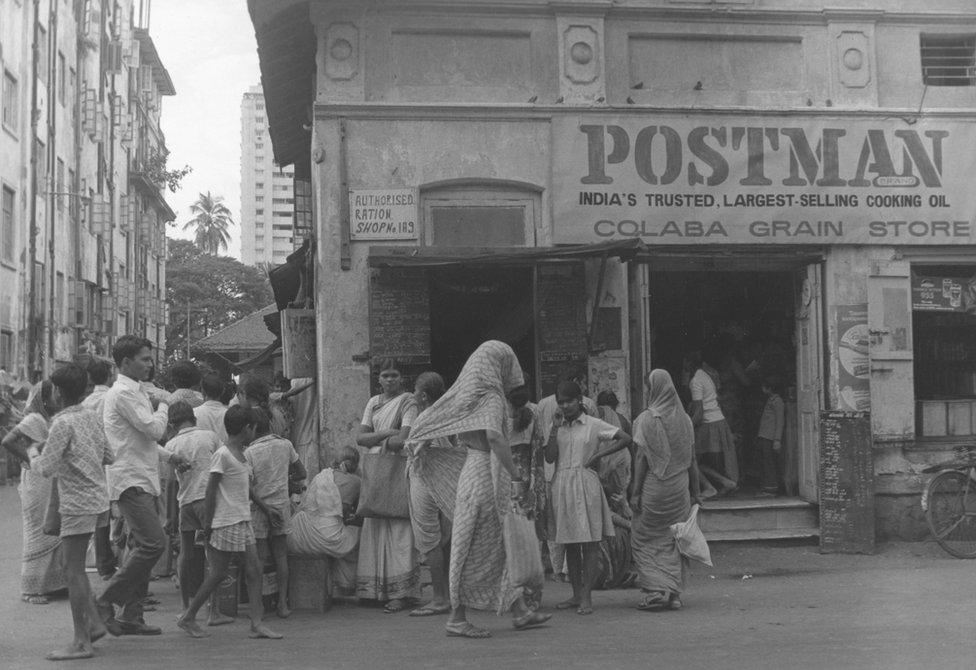

There was a time, not so long ago, when most Indians stood in queues for hours on end for essential goods and services.

I remember queues outside "fair-price shops", streetside taps, cinema houses and electricity offices. People lined up to buy cheap food and fuel, store up water, go to the cinema and pay bills.

Mailing a letter from the post office could involve several queues: one for buying stamps, another for weighing the letter. Even the dead queued up, waiting to be cremated.

India was an economy blighted by shortages - even the well-to-do had to "virtually" queue up for a car and telephone for years - and queues were linked to lack of supplies. When you booked a long-distance call on the creaky state-run telephone network, an automated voice reminded you that: "You are in the queue."

'Line of lines'

But, on the whole, the physical queues reminded many of us of Vladimir Sorokin's novel The Queue, external, a slyly funny tale about the chokehold of interminably long lines on the lives of people during Stalin's rule which, he wrote, had turned the Soviet Union into a gigantic "line of lines".

As India has enjoyed a quarter-century of economic growth, many of the familiar queues have disappeared. Others remain - the line for toilets, for example, is still driven by scarcity. (The queue waiting for household toilets, by one estimate, would stretch from Earth to the Moon, external and maybe beyond if all the people stood in a line.)

But after the past fortnight's "currency shock", when the government scrapped two high-denomination banknotes making up more than 85% of the notes in circulation, the long, unending queues of yore returned with a vengeance to India's cities and villages. It was almost a throwback to the days of the centrally planned, socialist economy.

The cash queues, not surprisingly, have also become India's biggest talking point.

A food line in Calcutta after rioting and looting in 1946

...and another outside a food shop in Mumbai in 1970

They have been gleefully used as a trope to mock the government for what many feel is a rash move that has hurt the poor most.

"It has clear that Stand-Up India has been a huge success. Most Indians, especially the poor, are now standing in one queue or another," tweeted an opposition politician. Others mused that they had aged standing in the lines - ironically to withdraw their own money.

The queues are evidence - again - of the fabled resilience of Indians.

Social bonding

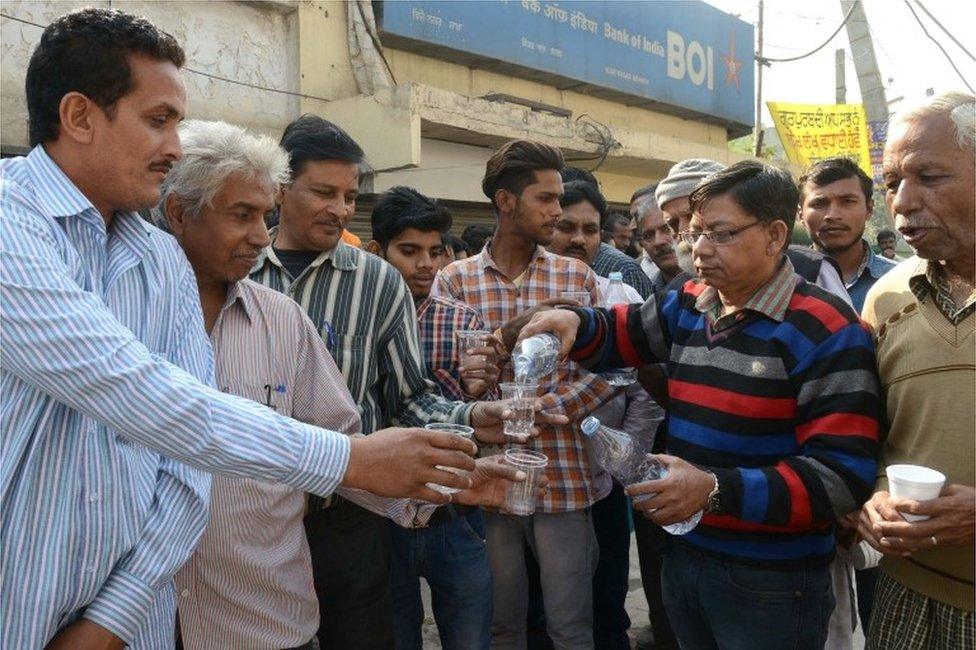

There has been no rioting in the lines so far, despite the Supreme Court's alarm, external. Although the media have reported more than three dozen deaths, external related to exhaustion from spending long hours in queues, people have been largely orderly and patient. The poor have wrapped themselves in blankets and queued up at the crack of dawn outside banks.

The lines have thrown up unlikely business opportunities for some. "Money mules" queued up to deposit other people's money for a fee; and a service let people hire a person in a queue for as little as 90 rupees ($1.30; £1) an hour.

The queues have also become places for social bonding. Reports spoke about people discovering old friends and finding dates. They brought mats and lunchboxes, reserved a place, and, according to one report, external, "almost turned it into an opportunity to relax, socialise and collaborate". Helpful citizens distributed water, tea and biscuits to the throngs.

The cash queues have been, by and large, orderly

Volunteers have distributed food and water to people in the lines

Families were struggling to withdraw money for weddings and stood in the queues for cash

The queues generated levity and triggered retribution. A cash-strapped groom, external was stranded in one on his wedding day. A woman spotted her "ex-lover in a bank queue" and called in her family and "got him thrashed", external.

A well-known author wrote, external that she didn't mind standing in line - "people-watching is fuel for the next novel". Ajay Gandhi, an anthropologist who spent more than 19 months researching queues in old Delhi, aptly summed up a queue in India when he wrote about a long line for railway tickets: "The queue was at once a scene of patience, frustration, resignation and lightness."

For the upwardly mobile middle class, the queues appeared to be an opportunity to find out how the other half lived, as they sometimes joined the poor and low-income working class to deposit or withdraw money.

A journalist wrote that, external she would "just remember faces - of simple, unassuming people, who do not have black money or not even enough white money, who believe in god and good, who laugh, cry, talk yell, do all kinds of jugaad [an Indian colloquial word that means ingenious improvisation in the face of scarce resources], yet always extend a helping hand - whenever, wherever".

Another scribe wrote that standing in the cash line was the "first time I was really being forced to behave like a citizen of this country".

A friend, she said, told her the queue was, indeed, a "great leveller".

That may not be quite true.

Temporary exercise

The middle class and the well-to-do have never really queued up in India. In a deeply divided and unequal society, family, caste and kin networks always helped us to get what we wanted without much distress.

Also, queues themselves have often been about gender and social entitlement: there are separate lines for women, VIPs (Very Important People), pensioners and freedom fighters. Only the long queues of people waiting to cast their ballots during elections flatten hierarchies.

"The idea that queues promote democracy and egalitarianism is a fallacy in India," Sanjay Srivastava, a sociologist, told me.

"The middle class and media sometimes romanticise queues. For most of us, standing in a line is a temporary exercise. If we had to queue up every other day for essentials, we would not be romanticising it."

"The queue was at once a scene of patience, frustration, resignation and lightness," wrote a researcher

He is right. Those who believe the cash queues phenomenon engenders a new state of community and citizenship are overstating their significance.

They should possibly visit the lines in government hospitals and crowded courts where millions wait patiently for treatment and justice. Or the night-long queues for water I found this year while travelling through drought-hit India.

Those are the real queues of pain - and they never went away.