India election 2019: How sugar influences the world's biggest vote

- Published

Some 30 million farmers are engaged in cane farming in India

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi held a recent election meeting in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, he was compelled to make a promise relating to sugar, a diet staple.

Farmers who grow cane in the politically crucial state ruled by Mr Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) were angry because sugar mills had not paid their dues in time. They held protests and blocked railway tracks. "I know there are cane dues. I will make sure every penny of yours will be paid," Mr Modi told the audience.

India's sugar mills are bleeding money and collectively owe billions of dollars to 50 million cane farmers, external, many of whom haven't been paid for nearly a year. Niti Ayog, a government think tank, says the arrears have reached "alarming" levels. More than 12 million tonnes of unsold sugar have piled up in factories. There is little incentive to export more as India's sugar price is higher than the international price.

Sugar is serious business in India. Around 525 mills produced more than 30 million tonnes of sugar in the last crushing season, which lasted from October to April. This makes it the world's largest producer, unseating Brazil. A large number of mills are run by cooperatives where farmers own shares proportional to the land they own and pledge their produce to the mill.

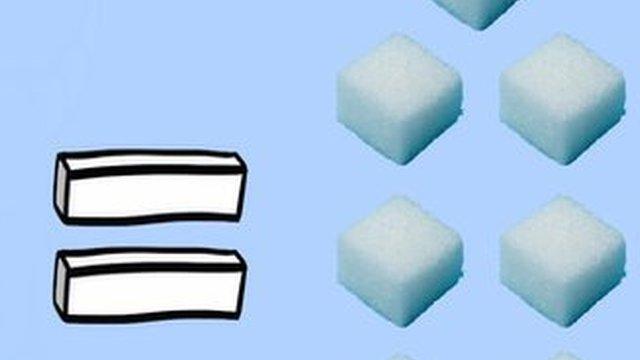

India is the world's largest producer of sugar

That's not all. Some 50 million farmers, tightly concentrated geographically, are engaged in cane farming. Millions more work in the mills and farms and are engaged in transportation of cane.

As with much of India's politics, cane growers appear to be a reliable "vote bank". Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, which together produce 60% of the country's sugar, send 128 MPs to the parliament. The price of cane can swing votes in more than 150 of the 545 seats in the ongoing general election, according to one estimate. Sugar is possibly the "most politicised crop in the world", says Shekhar Gaikwad, the sugar commissioner of Maharashtra.

India votes 2019

Indians are also voracious consumers of sugar. The bulk of the supply goes into making sweets, confectionary and fizzy drinks that are beginning to contribute to a rising obesity problem, like elsewhere in the world. "The world's sweet tooth continues to rely on cane sugar, much as it did four centuries ago," says James Walvin, author of How Sugar Corrupted the World.

Cane farmers have held protests, demanding higher crop prices

On the face of it, cane growers and owners of sugar mills should be happy.

The government sets cane and sugar prices, allocates production and export quotas, and hands out ample subsidies. State-run banks give crop loans to farmers and production loans to mills. When mills run out of cash, public funds are used to bail them out. "I earn around 7,000 rupees ($100; £76) from growing sugar every month. It's not a lot of money, but it's an assured income," says Sanjay Anna Kole, a fourth-generation, 10-acre cane farm owner in Maharashtra's Kolhapur district.

But protectionism may be yielding diminishing returns. Generous price support for the crop means the price at which mills buy cane has outstripped the price at which they sell sugar. Among large producers - Thailand, Brazil and Australia - India pays the highest cane price to farmers. It also spends more than Brazil, for example, in producing sugar.

Farmer Sanjay Anna Kole says cane farming provides an 'assured income'

The involvement of politicians may not be helping matters. Since the inception of the first mills in the 1950s, politicians have owned or gained control of them by winning mill co-operative elections. Almost half a dozen ministers in Maharashtra, India's second-biggest cane growing state, own sugar mills.

A study on the links between politicians and sugar mills by Sandip Sukhtankar, associate professor of economics at University of Virginia, found that 101 of the 183 mills - for which data was available - in Maharashtra had chairmen who competed for state or national elections between 1993 and 2005.

He also found that cane prices paid by "politically controlled" mills fell during election years, and that this was not entirely due to loss of productivity.

These mills have also been blamed for holding on to arrears and releasing them before elections to win over voters; and political parties have been accused of using money from the mills to finance campaigns. "One would think that perhaps political parties that don't benefit from links to sugar might have incentives to reform the sector, but we have seen parties everywhere want a piece of the action," says Dr Sukhtankar. "There are resources in the sugar industry to be extracted for political purposes."

Sugar stocks have piled up in factories across India

Whatever the case, India's world-beating crop is mired in crisis. The farmers and the mills grumble that they aren't getting a fair price for their crop and sugar respectively. "It looks like a sunset industry for me. There's no future in cane until the government completely overhauls farm policies," Suresh Mahadev Gatage, an organic cane-grower in Kolhapur, told me.

The unrest among the farmers is worrying. In January, several thousand angry cane farmers descended on Shekhar Gaikwad's office in the city of Pune, demanding the mills pay their dues in time. The negotiations lasted 13 hours.

One of the farmers' demands was to arrest a state minister, who was heading three mills in the state, and had defaulted on his cane dues. When negotiations ended way past midnight, authorities issued orders to seize sugar from the offending mills and sell it in retail. In India's lumbering bureaucracy, that took another eight hours because 500 copies of the orders had to be printed. "My office is pelted by stones every other day by irate farmers," says Mr Gaikwad.

Cane grower Suresh Mahadev Gatage says there is 'no future in cane'

Meanwhile, what is completely forgotten is how much sugar has hurt India's ecology. More than 60% of the water available for farming in India is consumed by rice and sugar, two crops that occupy 24% of the cultivable area. Experts say crop prices should begin to reflect the scarcity and economic value of water.

But before that, as Raju Shetti, MP and a prominent leader of sugarcane farmers, says, price controls should be eased and bulk corporate buyers like soft drink companies and pharmaceuticals should pay more for sugar.

"We need differential pricing for sugar. Cheap sugar should be only provided to people who can't afford it. The rest should pay a higher price," he told me.

"Otherwise, the industry will collapse, and farmers will die. Even politicians will not be able to save it."

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external

- Published29 April 2019

- Published3 February 2016

- Published4 April 2019