Why schools are at the centre of Delhi polls

- Published

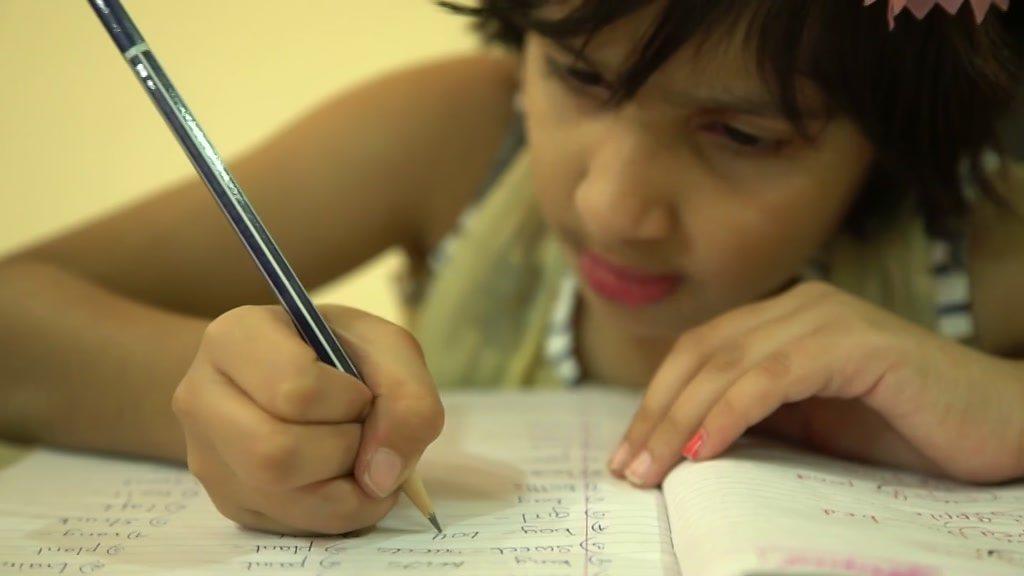

More than 1.5 million children go to government schools in Delhi

A few weeks ago, Arvind Kejriwal, the doughty chief minister of the Indian capital, Delhi, made an impassioned plea to voters in an election campaign meeting.

"We've worked hard to improve our schools, the education system. Who will take care of the education of your children if you vote for any other party? Just give it a thought," he said.

India's populist politicians don't usually talk about schools and colleges in stump speeches - education reform, they believe, doesn't fetch votes, because results take time, and voters appear to be keener on more immediate outcomes. "Today's politics wants instant results," says Delhi's education minister Manish Sisodia.

Mr Kejriwal's Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), a regional start-up, is seeking a second successive term in power in Delhi.

And Mr Kejriwal wants to prove populist politicians wrong: he's made education the centrepiece of his campaign.

His government's performance in education - along with healthcare - is an unusual campaign plank, and a consistent headline maker. AAP swept 67 of Delhi's 70 assembly seats five years ago, and hopes to repeat this performance on 8 February, largely on the back of its performance in education.

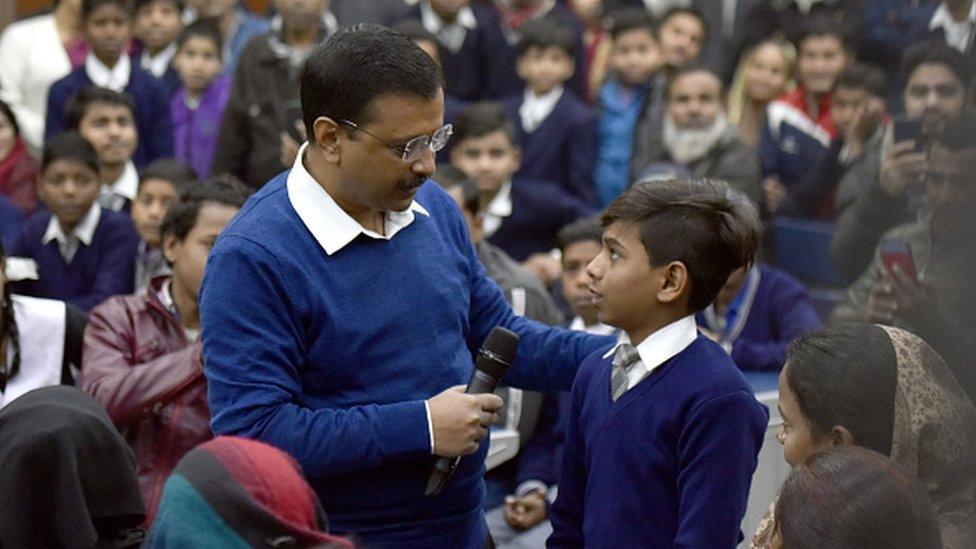

Arvind Kejriwal is seeking a second term on the back of his record in education reforms

Mr Kejriwal has much to crow about. His government runs 1,000 schools, attended by more than 1.5 million students. Education is free. In five years, he claims his government has succeeded in a way none of his predecessors have.

His main rival is the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The BJP has been running a bellicose counter campaign on a controversial new citizenship law, the stripping of Kashmir's autonomy and building a grand new Hindu temple. In other words, it's mostly about assuaging majority Hindu sentiments and promoting muscular nationalism.

The makeover

Mr Kejriwal has ploughed nearly a quarter of his government's $5.8bn (£4.40bn) budget into education - the highest in India - and appears to have spent the money wisely. (His predecessors in Delhi spent up to 16% of the budget on education; and India's states, on average, spend 14.8% of their budgets on education).

Investing heavily in education has helped change the gloomy image - slovenly and badly-run - of state-run schools in a teeming city of nearly 20 million people. "The assumption was only poor children go to these schools. The rich and middle class prefer to send their children to private schools," says Shailendra Sharma, an education advisor to Mr Kejriwal's government. "Anything free in India is perceived to be substandard."

CCTV cameras have been installed in government classrooms

But this year, Mr Kejriwal's schools, mainly attended by the city's underclass and children of poorer migrants, have outperformed their more expensive and posh counterparts. Some 96% of the 12th class students from state-run schools passed the school-leaving exam, compared to 93% from private schools.

Such results have received estimable praise, most recently from Nobel-prize winning economist Abhijit Banerjee.

'A liberating experience'

Education reforms are usually messy, but Mr Kejriwal's government appears to have chosen simple initiatives to achieve a significant turnaround.

Classrooms have been renovated, toilets are scrubbed regularly, and playgrounds cleaned. Students and parents alike have welcomed a controversial decision to put CCTV cameras in classrooms to monitor children. Smart-looking desks, digital learning, well-stocked libraries, functioning science labs, and special theme-oriented classrooms have helped make the once-dowdy schools attractive places of learning.

"Government schools," says M Shariq Ahmed, principal of a "model" government school, "have now become a very liberating experience for students, who come from stressed backgrounds."

Tens of thousands of classrooms have been revamped

Selected teachers have been sent on training and leadership courses at the National University of Singapore, and a leading Indian business school. Others have travelled to Finland and Cambridge in the UK to study school systems. More than 200 "mentor teachers" sit in classrooms and give feedback on five schools under their watch. The curriculum has been tweaked imaginatively - classes on "happiness" and business motivation have been introduced. Mega parent-teacher meetings are held in all schools several times a year, encouraging interaction between illiterate parents, first generation learners and teachers.

There's also been a substantial expansion of capacity to cater to a growing number of students - 34% of Delhi's 4.4 million school-going children attend government schools, and their numbers are increasing. By the end of the year, Delhi should have 55 new schools and 20,000 additional classrooms.

The 'segregation' controversy

The language of instruction in most of the schools is Hindi, with one English medium section for every class. Last year, more than a thousand children scored more than 90% marks on a bouquet of five subjects - a first. A whopping 473 students cleared an intensely competitive exam for admissions to India's top engineering and architecture schools, up from 150-200 in previous years.

There's been criticism about some of the teaching methods in Delhi's government schools. The most contentious is "separating" - critics call it segregation - performing and laggard students by putting them in different classrooms. Last year, education activist Kusum Jain went to a Delhi court challenging Mr Kejriwal's government to explain why students were "segregated". She says: "Segregation on the basis of intelligence is wrong at a time when we should all believe in inclusive education."

Schools hold special 'happiness' classes for children

Manish Chand, who worked as an intern teacher in a government school, says the ability-based "segregation" of students has "led to more divisions" among students. He found some teachers in his school calling students by the names given to the groups, and sometimes the "better performing students" refused to study or play with their more non-performing peers. "This worried me a bit because such exclusion defeats the purpose of peer-to-peer learning," he says.

But some teachers defend the system, and say it has actually helped improve results. Students, they say, are separated in different sections on the basis of their reading and numeracy skills. Several independent surveys have found that Indian school children's reading and writing skills don't match the class they are in - a 2018 study, external found that nearly 73% of children in class three could not read class two lessons. "By separating the students, we are trying to get the teachers to give special attention to the ones who get left behind and often end up dropping out," says Mr Sharma.

The parent-teachers meetings have become a big draw

There are other challenges. More girls (53%) go to Delhi's state-run schools than boys (47%), and most choose humanities. On the face of it, there's nothing wrong about this. But dig deeper and you find that the parents' motivation for sending their daughters to free government schools often reveals a deplorable gender bias: many of them simply do not want to spend money on educating their girls. They would rather spend their hard-earned money on sending their boys to private schools, where they enrol them in science and pay extra for coaching classes so they can ace their exams.

In the hardscrabble neighbourhood of Shadipur in north-eastern part of the city, 16-year-old Manisha Kohli, daughter of an out-of-work tailor, lives in a grotty one-room hovel, goes to a government school, and wants to become a businesswoman. "I want to do better than my father," she says. "That's what my school is inspiring to be."

That is possibly the most exciting change Mr Kejriwal's schools are bringing about: they are helping the poor dream.

Read more from Soutik Biswas:

- Published18 July 2019

- Published8 March 2017