Climate change: The world awaits India's net zero emission deadline

- Published

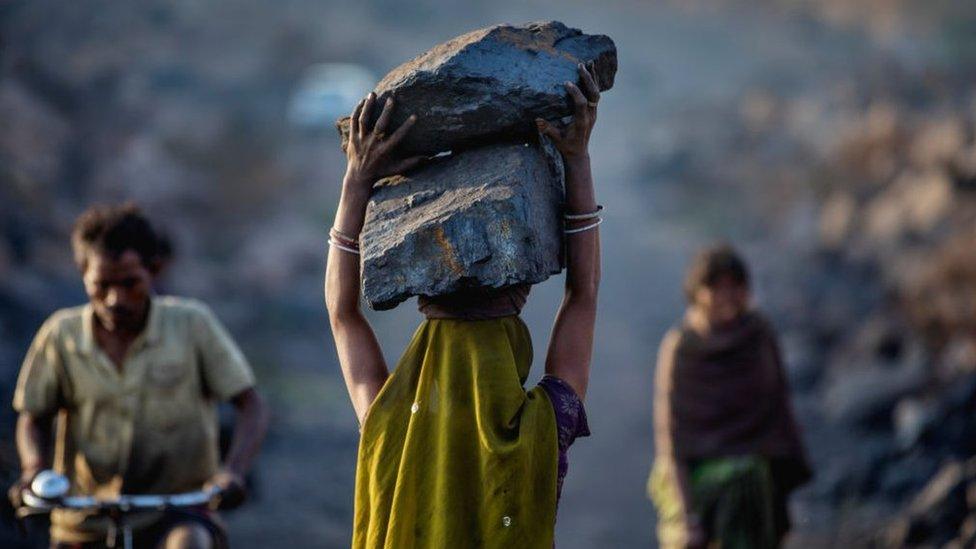

A woman at a mine in Jharkhand - India plans to increase coal production as part of its post-Covid recovery

US climate envoy John Kerry secured a modest win in announcing renewable energy plans with India last week - but got no clarity on how India plans to achieve its net zero emissions target.

Mr Kerry has been trying to agree ambitious carbon reduction targets with major emitters in a bid to reassert US leadership on climate.

China however rebuffed his attempts to separate climate from other disputes. "The US hopes to make climate co-operation an 'oasis' of China-US relation but if the 'oasis' is surrounded by 'desert', the 'oasis' will sooner or later become desert," FM Wang Yi reportedly told Mr Kerry.

India was happy for Mr Kerry to announce (for the second time - it was initially launched in April) the Climate Action and Finance Mobilization Dialogue (CAFMD), which is mainly aimed at helping India achieve its 450 gigawatts (GW) renewable energy target.

But there was nothing on how India plans to slash its carbon emissions to the required level.

Net zero means reducing greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible and then balancing out any further releases by absorbing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere - for instance, by planting trees.

China, the world's largest carbon emitter, has already announced it will be carbon neutral by 2060 and its emissions will peak before 2030 - although it has been criticised for building new coal plants.

The US, the second largest emitter, has set 2050 as deadline to reach net zero and it says it will decarbonise its power sector by 2035.

But the world's third-largest emitter India has neither announced the net zero year nor has it submitted to the UN an updated climate plan with raised carbon-reduction ambition, as required by the Paris agreement every five years.

India Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav (left) and US climate envoy John Kerry met in Delhi last week

The UN, however, says of the 191 countries taking part in the agreement, only 113 have so far come up with improved pledges.

Analysis of the climate plans submitted so far shows that emissions are actually set to rise by 16% by 2030, which could lead to a temperature rise of 2.7C (4.9F) above pre-industrial levels.

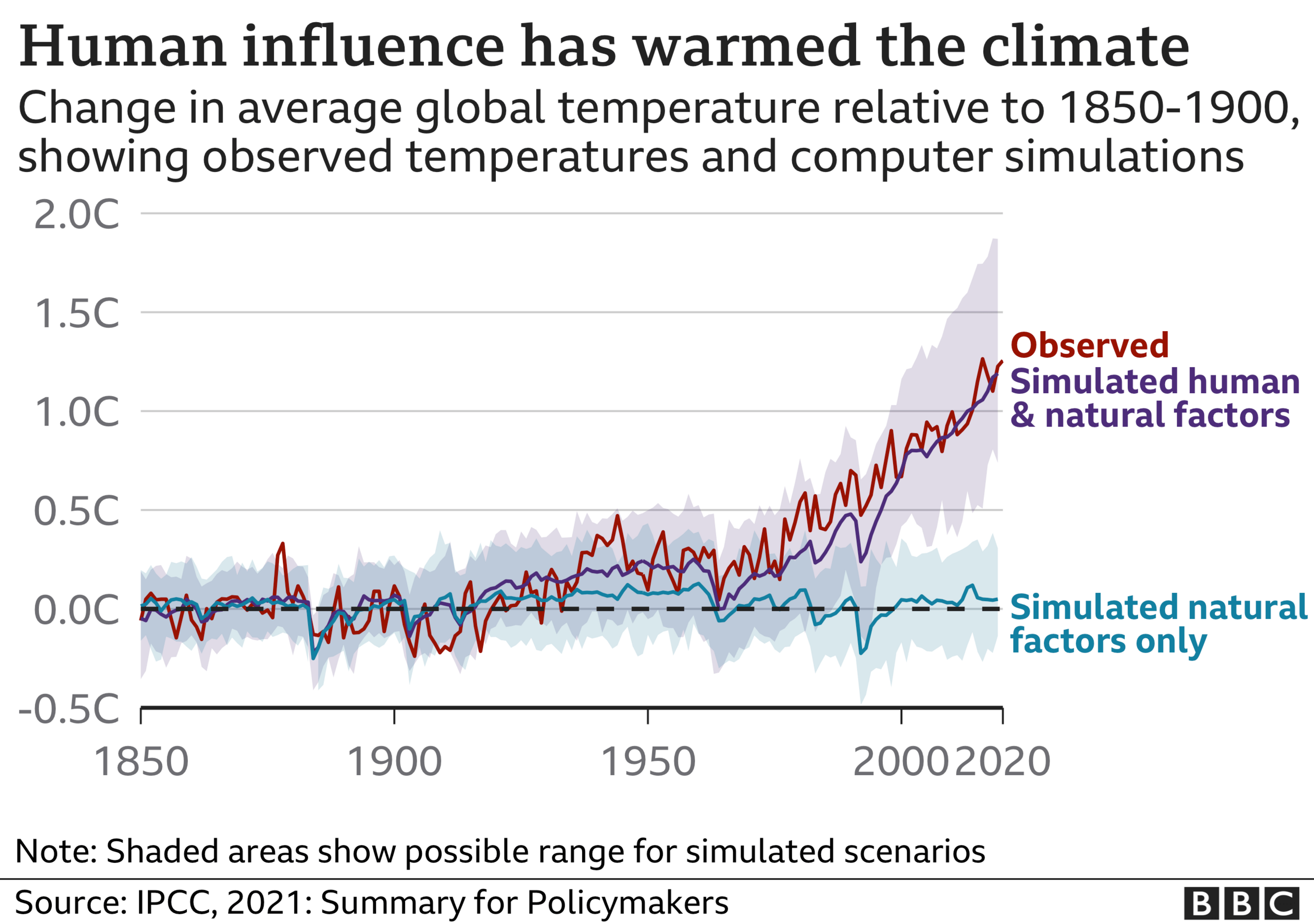

The Paris climate agreement aims to limit global average temperature rise to well below two degrees, and strives for 1.5 degrees higher than the pre-industrial period to avoid dangerous climate change.

Scientists say the world has already warmed by 1.1 degrees since then and global carbon emissions need to be cut by 45% by 2030 to stop the Paris target from slipping out of reach.

The recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has even warned that some of the earth's climate systems may have already been dangerously disturbed because of the rise in temperature.

With countries expected to submit their updated plans, known as Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs), before the upcoming major climate summit, COP26 in Glasgow, many eyes are now on India.

During his Delhi-visit last week, Mr Kerry did not put the spotlight on India on this issue, at least not in public, but he did stress on the net zero agenda.

"Beyond just deploying renewable energy, my friends, we need to develop, demonstrate and scale up emerging technologies that will be crucial for the net zero transition, let me just emphasise this," he said during the launch of the CAFMD.

During the same programme, India's Climate Change Minister Bhupender Yadav, neither mentioned net zero nor talked about any new carbon-reduction ambition.

Unusual heavy rains and floods have become common in many Indian cities

Instead, he defended India's present climate plan. "India's climate actions are rated high in many independent assessments….India's NDC has been rated as two degrees Celsius compatible."

In its first NDC, India had committed to cut carbon emissions by 33-35% from 2005 levels within 2030 and Indian authorities say the country is set to exceed the target.

But scientists have calculated that there is a huge gap between countries' carbon-reduction pledges in their first NDCs and what is needed to attain the Paris climate goal.

Hence there is a need for increased carbon-reduction ambition in the near-term and net zero emission target for the long-run.

But India has been arguing that it should not be expected to make deep carbon-cuts like developed countries because it is still developing and fighting poverty while having to rely on an energy-mix that largely relies on fossil fuels.

While going big on renewable energy, particularly solar power, the Indian government has announced plans to significantly increase coal production as part of post-Covid economic recovery.

"Good to see @ClimateEnvoy John Kerry. Continued our discussions on climate action and climate justice," tweeted Indian foreign minister S Jaishankar after meeting Mr Kerry last week.

So, by the end of his trip, Mr Kerry did praise India's track record on renewable energy but had nothing on whether India had committed itself for net zero and increased emission-reduction ambition.

"I'm confident that India is going to announce one thing or another going into COP [26], as will many other nations we haven't heard from yet. So, I anticipate increased ambition from a lot of different places," he was quoted as saying by Indian newspapers.

If India really does what Mr Kerry hopes it would do, it might unintentionally help the US in its bid to regain leadership in global climate regime - particularly when Washington faces an "unfriendly" China on the climate front as well.

But what if India chooses not to do so and if China continues with its "no co-operation if it is just climate" position?

Will the two team up to resist developed countries as they have done during past climate negotiations even when there were issues between them?

There are no easy answers.

But what India and China do will have an immense influence on global climate action - or inaction, for that matter.

You may also be interested in:

The Himalayan village that confiscates single-use plastics

Related topics

- Published25 October 2018