Pew survey: Do Indians think women make better politicians?

- Published

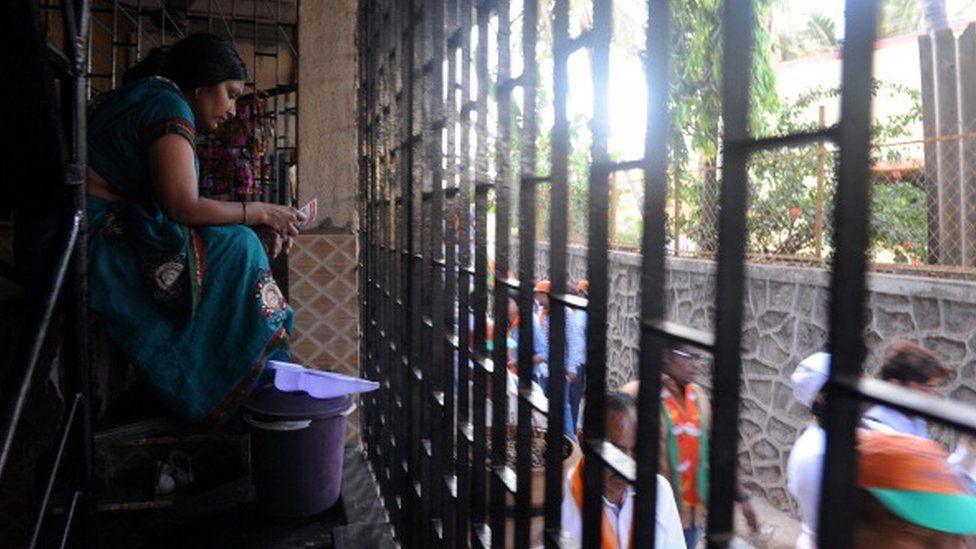

Priyanka Gandhi, a leader of the Congress party, belongs to the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty

Most Indians say that "women and men make equally good political leaders", and more than one in 10 feel that women generally make better political leaders than men, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of nearly 30,000 adults throughout India.

Only a quarter of Indian adults believe that men make better political leaders.

Does this finding reflect a strong demand for female leaders? Indian women have been ministers, president and prime minister - Indira Gandhi was only the second woman to head a state in the 20th Century. Some 14% of MPs in the current parliament are women, up from 5% in the first election in 1952.

Yet, political participation is poor. Only 8% of the more than 50,000 candidates in federal and state elections are women, according to a 2019 report by the Association for Democratic Reforms, external, a research group. India ranks 144 among 193 countries in a global ranking of women in national parliaments, external. A bill to reserve a third of all seats in the national parliament and state legislatures for women has been hanging fire since 1996.

Researchers like Alice Evans, a social scientist at King's College London, are sceptical about the latest findings. "We should not necessarily see this as a strong demand for female leaders. There is plethora of evidence pointing to discrimination against women in India," Dr Evans, who is researching a book on gender equality, told me.

A women's electoral victory in India has no "demonstration effect", said Dr Evans. Other parties are no more likely to field women candidates and women in nearby constituencies are no more likely to stand for office.

"Restriction of mobility has meant that Indian women struggle to be electorally competitive - they have little opportunity to congregate with peers, amass knowledge of the wider world, forge alliances with unknown men, and collect campaign funds," she said.

Four-fifths of Indian women are engaged in unpaid chores

Many of India's women leaders, say researchers, tend to be privileged - wealthy, upper caste or members of family dynasties. "For ordinary women, politics is out of reach," said Dr Evans.

Separate research in OECD countries, external has shown that representation of women in politics is higher in countries with the proportional representation system, where the distribution of seats hews closely to the proportion of total ballots cast for each party.

One reason, researchers suggest, is that people vote for the party rather than individuals, and politicians - including women - can take career breaks and do not need strong and sustained networks with local people and businesses to win.

But in countries like India and the UK with a first past the post (FPTP) electoral system where the candidate with the highest number of votes in a constituency is declared the winner, representation of women in politics could be stymied. Politicians must establish personal credibility and forge long-term links with constituents. Interruptions in career can be costly.

However, in domestic settings, Indians tend to say men should have more prominent roles than women, according to the Pew Survey.

About nine in every 10 Indians agree with the notion that a wife must always obey her husband, including two-thirds who completely agree with this sentiment. Indian women are also only slightly less likely than Indian men to say they completely agree that wives should always obey their husbands.

That's not entirely surprising. India remains predominantly rural, and many women continue to be sequestered with very few friends. This limits their opportunities to mingle and critique inequalities. "Men enforce their authority and women endure it," said Dr Evans.

Measures to prevent female foeticide have yielded modest results

The Pew survey also found that many Indians express egalitarian views toward some gender roles in the home: 62% of adults say both men and women should be responsible for taking care of children.

But traditional gender norms still hold sway among large segments of the population: roughly a third of adults feel that child care should be handled primarily by women.

Similarly, a slim majority (54%) says that both men and women in families should be responsible for earning money, but many Indians (43%) see this as mainly the obligation of men. And most Indian adults say that when jobs are in short supply, men should have greater rights to employment than women.

The perception of the male breadwinner is both a consequence and cause of low female employment, creating a chicken-and-egg situation, says Dr Evans.

She believes Indian families face what she says is an "honour-income trade off": female employment rises if the woman earns well enough to outweigh the loss of family honour. Female graduates are pursuing careers in IT, engineering, telecoms, finance and hospitality. "But job creation remains low in India. Job queues are very long, and women are at the back," said Dr Evans.

A worrying finding of the survey is that many Indians see sex-selective abortion, despite the illegality of the practice, as acceptable in at least some circumstances.

Four in 10 Indians say it is either "completely acceptable" or "somewhat acceptable" to "get a check-up using modern methods - antenatal sex screening - to balance the number of girls and boys in the family", a euphemism to connote sex-selective abortion.

India needs to offer more opportunities to women

Differences by religion on this question are modest: roughly four in 10 - Hindus (40%), Muslims (37%), Christians (43% ), Sikhs (38%) and Jains (40%) - say this is acceptable. At least one in five people in nearly every state say sex-selective abortion is completely acceptable.

This, believes Dr Evans, is also linked to low female employment as parents continue to want at least one son to provide for them in old age. If there were more jobs for women, if daughters could get decent jobs and provide for their parents, then a preference for sons would probably diminish as it has in South Korea and parts of China, she said.

So what do the findings tell us about gender equality in India?

Indian adults are roughly in line with the global median in their support for equal rights for women, according to Jonathan Evans, the lead researcher of the survey. But only one of the 61 countries surveyed by Pew - Tunisia - has a higher share than India who agree completely with the idea that men should have greater rights to a job than women when jobs are scarce.

Yes, more Indian women are getting educated, and women's movements have secured laws on dowries, divorce, domestic violence and inheritance. Women have publicly challenged traditional norms by lighting funeral pyres of family members.

"But the women's capacity to claim these rights and challenge patriarchal guardians is constrained by social seclusion and economic insecurity. For women to claim their rights they first need to come out of their homes. That requires more jobs-oriented growth and safer public places," said Alice Evans.