Mansiya VP: Kerala dancer who took on religious conservatives

- Published

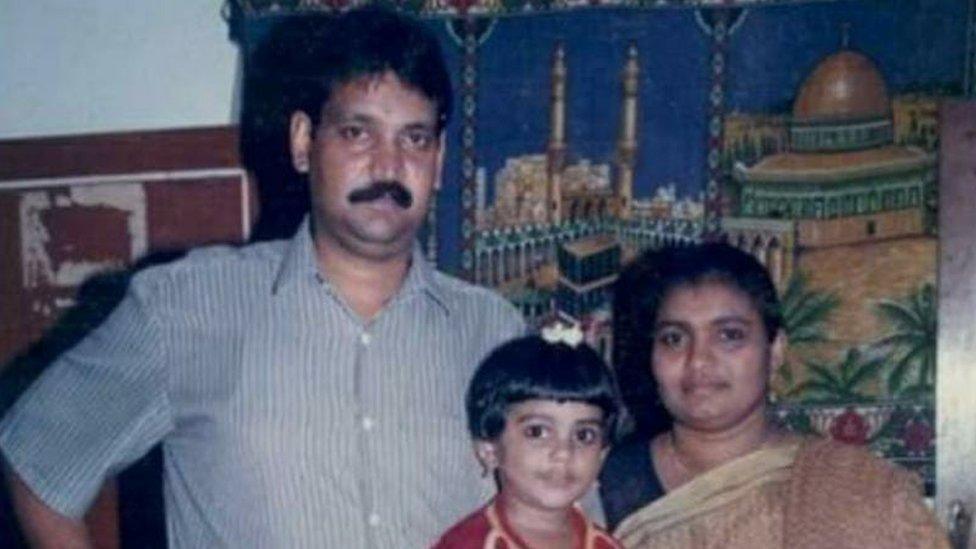

Mansiya's parents encouraged her to learn classical dance

Mansiya VP was three years old when her mother signed her up for Bharatanatyam, a centuries-old Indian classical dance form that originated in temples.

It was an unusual choice for a Muslim girl from Malappuram, a district in the southern state of Kerala.

But Mansiya's mother, Amina, was determined.

So her two daughters learnt not just Bharatanatyam, but also other classical dances such as Kathakali and Mohiniyattam.

It wasn't easy - conservative Muslims from the community said the girls shouldn't learn "Hindu dances". The family's persistence often made headlines, external.

But last week - 24 years after she first donned a pair of Bharatanatyam anklets - Mansiya was in the news again. This time, it was because of a viral Facebook post, external she wrote after a Kerala temple refused to let her perform at its annual festival.

The reason: she wasn't Hindu.

The organisers had earlier accepted her application, but temple authorities, who barred her from dancing at the venue, defended their decision, external, saying they had to follow tradition.

The incident has become yet another fault line in an increasingly polarised country.

But an unfazed Mansiya wrote in her post: "I have reached here after suffering far worse discrimination. This is nothing to me."

The first hurdle

"We had some financial difficulties but we were really happy," Mansiya - now 27 and doing a PhD in Bharatanatyam - says about her childhood.

Dance entered their lives after their mother saw a performance on TV and became "fascinated by the colourful costumes".

Backed by her husband VP Alavikutty, who was then working in Saudi Arabia, Amina ferried Mansiya and her elder sister Rubiya to dance classes and ensured they practised every day.

Their life was divided between school, dance and religious studies - Amina was a devout Muslim. Mr Alavikutty, who moved back to Kerala when Mansiya was young, wasn't very religious but had no problems with his wife or children's faith.

Every day after school and on weekends, the family would take buses to reach some of Kerala's best dance teachers - from whom Mansiya and Rubiya were learning around six dance forms.

Sometimes these journeys would span hundreds of kilometres and cover several districts in one day.

"It was hectic, but we were used to the routine. I liked it," Mansiya says.

Young Mansiya with her parents

The children began performing at temples and youth festivals - regular venues for aspiring dancers in Kerala.

But trouble began when their local mosque committee started objecting.

After that, Mansiya says, committee members and local madrassa teachers would ask the girls to promise not to dance anymore.

Mansiya, too young to understand the situation, would agree, but Rubiya often returned home in tears.

But Amina and Mr Alavikutty would reassure the girls that they could continue dancing.

"I don't know how they did it, but they never showed us their worries," Mansiya says.

Mr Alavikutty - who acted in street plays when he was young - says their conviction came from knowing that they weren't doing anything wrong.

But things turned ugly after Amina was diagnosed with cancer in 2006.

While Mr Alavikutty struggled to raise money for treatment, Mansiya says an offer of financial help from abroad lapsed because the mosque committee - still furious over the girls pursuing classical dance - refused to endorse their request.

"I would go with my mother every day as she pleaded for help from the members," Mansiya recalls.

The trauma, she says, made her rethink her relationship with religion.

When Amina died in 2007, Mansiya says she was denied a resting place at the local cemetery.

The next few years were lonely and hard - especially after Rubiya left home to study in neighbouring Tamil Nadu state - but Mansiya's love for dancing and her father's support kept her going.

Religious divides

India's religious complexity has often thrown up fascinating contradictions - a 2021 Pew study found that the majority of people across faiths support both religious tolerance and religious segregation.

Syncretism has long been enmeshed in daily life and culture - though its limits are often put to the test. Some of India's most beloved classical musicians are Muslim. Their music is often intensely devotional and many of them, such as Ustad Bismillah Khan and Allauddin Khan were devotees of Saraswati, the goddess of learning, while practising their own faith.

Mansiya reckons that growing up, she and Rubiya - fondly called the "VP sisters" - "must have danced at almost every temple in Malappuram district". They were greeted with love and appreciation everywhere.

The only jarring instance she can remember is at one temple where a committee member objected to them because they were Muslims.

"But after our performance, he was so moved he came and hugged us," she recalls.

When the Koodalmanikyam temple in Thrissur district invited applications for its annual festival, she contacted the organiser, who asked her to send in her details. When asked what kind of details, he described what sounded like an artists' resume. Religion wasn't mentioned, says Mansiya.

She had been practising for weeks when another organiser called and told her she couldn't perform as the temple didn't allow "non-Hindus" to enter. Most Hindu temples in India allow people of all faiths to enter and even pray. But several - including some famous ones - insist that only Hindus can go beyond a point into areas where rituals take place.

Mansiya with her father VP Alavikutty

After the post went viral, temple authorities said, external they had to reject Mansiya's application as they were "bound to follow and practise existing traditions".

She received support from politicians and artists - three Hindu dancers have withdrawn, external from the upcoming 10-day festival in solidarity.

Her family has also stood firmly behind her - including her Hindu in-laws, who regularly visit temples.

Mr Alavikutty is unbothered by the controversy - it was a "trivial issue", he says, compared with what they had been through.

Mansiya says she wrote the Facebook post for one reason.

"If at least one person reads it and realises that art has no religion, I will be happy."

You may also be interested in:

The Bulgarian with a passion for Indian classical dance

- Published23 February 2022