'Fridge murder': Is India seeing a wave of gruesome copycat murders?

- Published

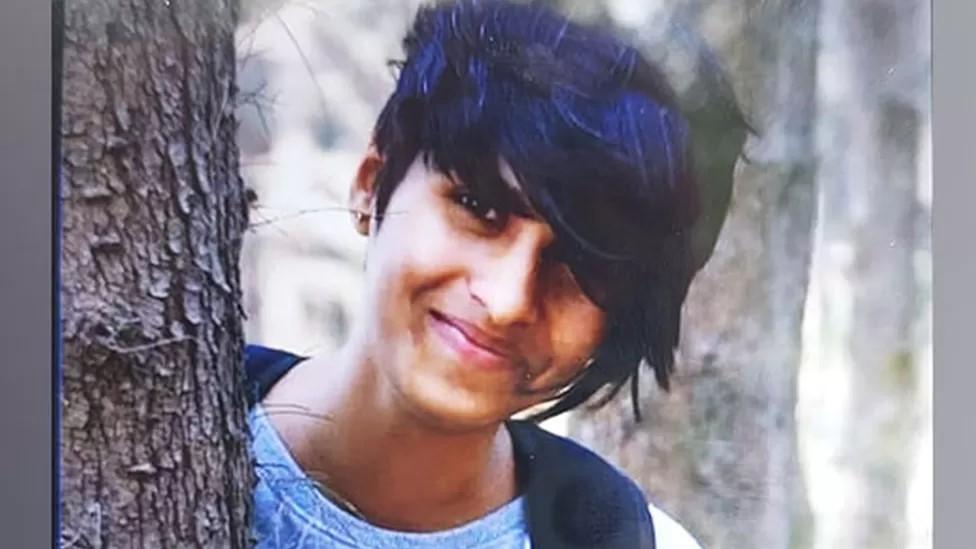

Shraddha Walkar's murder made headlines in India

Some 30 years ago, a scientist in the Indian capital, Delhi, killed his wife following an altercation at home, chopped her body into parts and stuffed them into a trunk.

He then travelled with the trunk more than 1,500km (932 miles) in a crowded train to the southern city of Hyderabad and checked into a hotel near a marsh. Over the next few days, he disposed off the remains in a muddy lake. One day, a stray dog scavenging for food yanked a human hand out of the bog.

"The man dismembered the body and took the parts to another city to eliminate evidence. There was nothing new about a 'dismemberment murder'. But we wondered whether the method of disposal of the body [parts] was inspired by a book or film," recounts Dependra Pathak, a senior Delhi police official.

A rash of similar killings in recent months have dominated headlines in India, triggering speculation about whether these were copycat murders. In each case, the victim had been killed, chopped into pieces and stuffed into a refrigerator or a suitcase. The remains had then been ferried in a suitcase or a bag and scattered in a sprawling ground, desolate roads or a forest.

The full crime data in India doesn't offer any clues. More than 29,000 cases of murder were registered during 2021, a marginal increase of 0.3% over 2020. Most of the killings were provoked by "disputes", followed by "personal vendetta or enmity" and "gain [for money]". We don't know how many victims were dismembered or what weapons were used for the killings.

News networks reporting near a pond in Delhi where Walkar's body parts where allegedly thrown

"Copycat murder and murder suicides are real. The media spreads the contagious behaviour: imitation," wrote Loren Coleman, a cultural behaviourist who studied how media's saturated coverage of crimes impacted people.

Aftab Poonawala, who was charged in November with the murder of his partner Shraddha Walkar, was apparently inspired by Dexter, a US crime drama featuring a forensic blood splatter analyst who moonlights as a vigilante serial killer.

Police claim that Poonawala strangled Walkar, chopped her body into 36 pieces, stored them in a refrigerator and dumped them in a forest near their home.

"Sensationalising such killings can create hysteria among people, and even inspire copycat acts," says Anuja Kapur, a criminal psychologist.

Yet, sleuths and crime psychologists say there's no reason to believe the India's rash of "fridge" and "suitcase" murders - as a sensation-loving media has described them - are copycat crimes. "Copycat crimes are real. But in my experience, the methods of eliminating evidence borrow more from films and novels rather than the crime itself," says Mr Pathak.

For one, dismembering corpses after killing a victim to get rid of the evidence is an old and common crime. The media's "bad news bias" - oversaturated coverage of sensational murders - spurs increased reporting of similar crimes, creating an impression that such killings were becoming more frequent.

"Dismemberment murders are relatively rare but they also happen all the time. It's just that many cases are not reported by the media. I am looking into three cases of murder and dismemberment that haven't been reported by the media at all," says Sudhir K Gupta, head of forensic medicine at Delhi's All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

Police in Delhi looking for remains of a man who was allegedly killed by family members in November

When Dr Gupta began his career as a forensic surgeon in India three decades ago, he would come across cases where the victims were called out of their homes, murdered in desolate areas and their corpses were thrown in the jungles.

As the country urbanised and more families became nuclear, more murders were committed in less-crowded homes, and, in some cases, the corpses were dismembered and disposed off.

"Forensic reconstruction of the events leading to the murder and identification of the victim can become a challenge when corpses are dismembered," says Dr Gupta. "But even a detailed examination of human bones can tell us the gender, age, date of death and even the probable case of death."

International studies offer some clues about "dismemberment murders".

A study of 13 cases from a sample of cases spanning 10 years in Finland found that none of the victims were strangers to the offenders, and nearly half were partners or family members. At the time of the killing, the study found, the majority of the offenders were jobless, and none had been in any occupation that required knowledge of human bodies or handling of corpses.

Another study of 30 homicide cases involving dismembered bodies over half a century by the department of forensic medicine in Kraków, Poland found that these murders were usually not planned, and were committed by offenders who were in "close relationship with victim (family or friend) in the same place as the killing - the home of the perpetrator". A separate study by the Boston University school of medicine showed that 76% of dismembered crimes were committed by men.

Very little is known about the patterns of such "dismemberment" killings in India. What is also not known is how many murderers end up surrendering to the police after the act, and how many try to conceal evidence by dismembering or mutilating a corpse.

"But what we know is that many of the these killings reveal the infirmities in modern-day social relationships in India, like tensions in troubled marriages, extra-marital affairs, live-in relationships," says Mr Pathak. "That is when things often go out of control."

Read more by Soutik Biswas