Oscar nominee RRR: Why the Indian action spectacle is charming the West

- Published

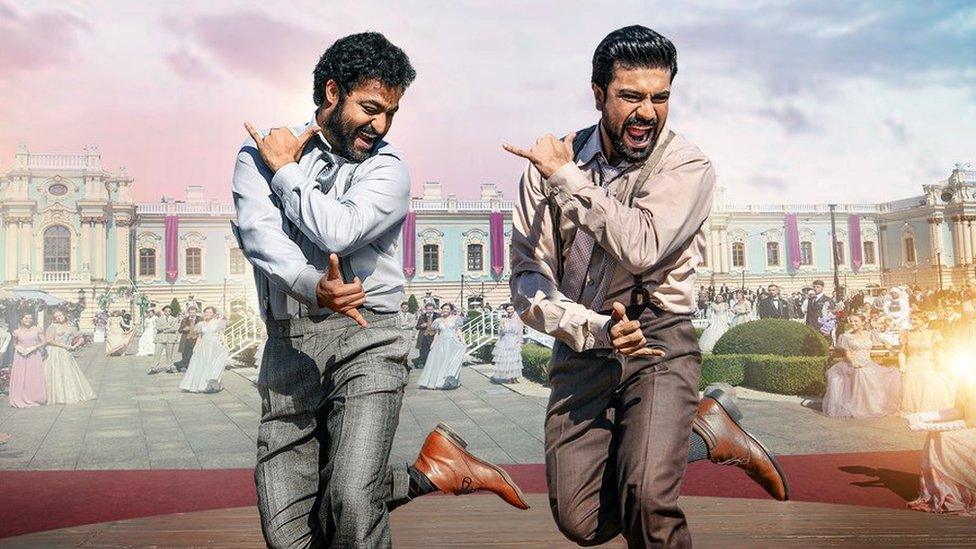

RRR features Telugu superstars Ram Charan and NT Rama Rao Jr

It has been 10 months since action-fantasy film RRR hit theatres in India, but the conversation around it hasn't died down. As the movie rides its popularity wave into the Oscars, the BBC's Meryl Sebastian unpacks why it has captivated viewers around the world.

Director SS Rajamouli has said that he made RRR mainly for Indians - people living in the country and the diaspora.

But since its release, the movie - which features Telugu-language stars Ram Charan and Jr NTR, and tells the fictional story of two real-life Indian revolutionaries fighting against British rule - has pushed many boundaries.

It has grossed more than 12bn rupees ($146.5m, £120m) globally, spent weeks in the top 10 on Netflix US and is now breaking box-office records in Japan. It has been included in several prestigious lists of best films of 2022, including that of the British Film Institute and National Board of Review in the US.

On Tuesday, Naatu Naatu, a catchy, exuberant musical number from the film, was nominated for Best Original Song at the Oscars.

It had earlier won a Golden Globe award for best original song, and both the song and the movie also won big at the Critics' Choice Awards in Los Angeles. BBC Culture film critics Nicholas Barber and Caryn James included it in their top 20 films of 2022.

Naatu Naatu has been nominated for Best Original Song at the Oscars

Rajamouli's joy and surprise at the movie's global reception is evident in his many interviews.

"When we started getting appreciation from the West, we thought, 'These guys must be friends of the Indians who went to watch the film'," he joked recently on the US talk show Late Night with Seth Meyers.

When RRR first released in the US, it wasn't different from other mainstream Indian films, says New York-based critic Siddhant Adlakha, a member of The New York Film Critics Circle which chose Rajamouli as best director in December.

"On opening weekend, the audience was mostly Indian," Adlakha says. "But a few weeks in, the demographics had totally shifted."

RRR serves up spectacular visuals and extravagant set pieces

Word about the film spread as people flocked to watch it in theatres, critics wrote rave reviews and A-list Hollywood directors - including Anthony and Joe Russo, Edgar Wright, Scott Derrickson and James Gunn - praised it.

American distributors have said they screened the film after seeing the enthusiastic public response to it.

This reception is "different from any [Indian] film in recent memory", Adlakha says.

Social media videos from screenings show people hooting and cheering as they watch the movie. The boisterous energy on display - common for films with superstars in Indian theatres - is a rare sight in the US.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

At a screening hosted by director JJ Abrams at the iconic Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles, people rushed to the stage to dance to Naatu Naatu.

"RRR is sort of introducing audiences, and even filmmakers here, to a different kind of movie-watching ritual, which they may not be used to - which is partially why even Hollywood filmmakers have been drawn to it," Adlakha says.

While the film's storytelling and confident execution have drawn viewers, the timing also helped.

"RRR is loud, it's brash, it's over the top. This was the movie people were waiting to go back to see - in theatres, or even at home on Netflix," says Elaine Lui, a TV host and founder of the entertainment news site LaineyGossip.

Though RRR wasn't India's official entry to the Oscars, the hype around it had put it in the running for nominations, with support from a host of Hollywood directors and stars who've called it an "absolute blast".

Trade magazine Variety had predicted, external the film could be nominated in categories including Best Film, Best Director, Best Cinematography and Best Original Song - it finally made it only to the last category, but that's unlikely to damp public enthusiasm.

"In the industry, the 'buzz' is a big deal," Lui says. And RRR has become part of watercooler conversation. "Everybody on the weekend, or at parties right now is saying, 'Did you see RRR?'"

Big names in Hollywood have publicly praised RRR

For many in the West, the film feels new and exciting as the US box office has been dominated by franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Fast & Furious in recent years.

"When blockbusters here can be very cynical or tongue-in-cheek, or when they're churned out like factory products without much care for the moving image, a film that's as sincere and well-crafted as RRR was bound to break in eventually," Adlakha says.

And in true Rajamouli style, RRR serves up spectacular images, multiple extravagant set pieces and imaginative storytelling to provide a unique cinematic experience.

One of the standout scenes in the film - when the heroes first meet - shows them riding a horse and a motorbike before they propel themselves off a bridge to rescue a child caught in a fire.

"American audiences aren't generally used to this sort of maximalist spectacle," Adlakha says, adding that the film is so "well put together" that it works with people "from any cultural background".

It also represents what people outside India expect from Bollywood and Tollywood (Telugu) films - visually stimulating, lot of people, lot of action, ambitious - but "without being a cliche", Lui says.

Many Indian critics have pointed to the use of Hindu iconography in RRR

RRR's success in India wasn't a surprise - Rajamouli was already a household name, thanks to his earlier blockbuster duology Baahubali, and expectations were high for his new star-studded epic.

But the film received middling reviews from several critics, who pointed to its problematic politics, use of Hindu iconography and appropriation of tribal culture.

In India, cinema as a medium has become extremely politicised, says writer and film critic Sowmya Rajendran. So RRR's appropriation of two real-life activists who fought for tribal rights and against the British, and its reimagination of them as Hindu mythological heroes invited closer scrutiny here, she says.

But Western audiences see RRR largely "as an anti-colonial narrative because that's the politics that's immediately apparent to them", Rajendran adds.

In the US, a handful of publications have attempted to address this.

While many say the symbolism goes over their head, the criticism is also becoming a part of the discourse around the film, Adlakha says.

"Even if it's just so people can have a more complete grasp on the images they're seeing and enjoying," he says.

While these conversations evolve, one thing that's certain is that Rajamouli and team have breached barriers both within the Indian film industry and outside.

And this may only be the beginning: Rajamouli's next step could be making a Hollywood film, external which, he says is "the dream of every filmmaker across the world".

Read more India stories from the BBC: