Indian fashion designers face eco-chic dilemma

- Published

Fashion designers are trying to make their work more mindful

At last month's Lakmé Fashion Week in India, conversations about making fashion more sustainable took centre-stage. But are the country's designers ready for this?

The four-day event - organised jointly by beauty company Lakmé, billionaire Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Brands and the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI) - is one of Indian fashion's biggest highlights.

While it had all the essential ingredients - glittering catwalks, clinking wine glasses and fashionistas in the front row - what grabbed eyeballs was a competition encouraging young designers to use eco-friendly materials to create outfits.

The event is part of a wider ambition among Indian designers aiming to make sustainability the driving factor of their businesses.

Many say they are trying to shrink their brands' environmental footprint - some are completely shifting to reusable materials, experimenting with fabrics made from used carpet or agricultural waste and eco-prints of plants and flowers. But experts say a lot more needs to be done, given the magnitude of the challenge.

This year's Lakme Fashion Week dedicated a day to the theme of sustainability

India's fashion industry is expected to grow at a staggering rate to reach $115-125bn, external by 2025, making it an important player on the global stage. Like elsewhere, it's the fast fashion market which is blamed for incurring maximum damage but experts say some of the responsibility also lies with the luxury segment.

More so since this segment has been growing rapidly in recent years, propelled by an emerging crop of young Indians with higher disposable incomes.

"Big designers have fashion shows every year and new collections every season, which means they too are creating clothes at a constant pace," says Pooja Singh, fashion and luxury editor at Mint Lounge newspaper.

So increasingly, the industry is facing repeated allegations of hypocrisy - of causing too much damage and doing very little to combat it. Critics say Indian designers sometimes use terms such as sustainability and eco-friendly for marketing campaigns without actually practising what they preach. Some designers reject the accusation, but other industry insiders agree it is a serious challenge.

Jaspreet Chandok, group vice-president of Reliance Brands which has invested heavily in the luxury market in recent years, says there's no simple answer to how luxury fashion can tackle climate change because everything is "work in progress".

"But what we do bring to the table are innovative materials and technologies to bridge the gap between luxury and sustainability," he says.

India's luxury market has grown exponentially over the years

Implementing these changes, he says, will take time, and the solution cannot be to ask people to stop making or buying new things. "After all, the industry allows people to express themselves and brings so much joy. It also provides employment to millions of workers."

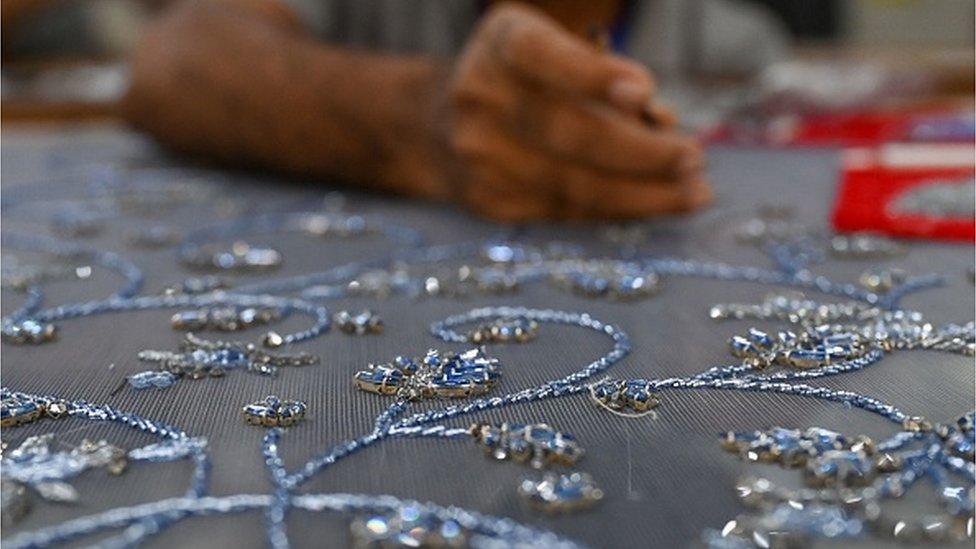

While sustainability is often seen as only related to the environment, in the Indian context, it should also include improving the working conditions of artisans who form the backbone of the fashion market. Some of the biggest names on the runways of Paris and Milan quietly rely on these highly-skilled workers to produce their fabulous hand-made outfits and India is one of the largest exporters of garments and textiles at $44.4bn, external.

But there have been allegations that they work in exploitative conditions, a trend which critics say has continued under Indian labels. In 2020, The New York Times reported that one of India's best-known designers was facing legal action from workers over unpaid wages.

Mr Chandok, however, says that a lot has been done to tackle the problem and workers are receiving better pay and opportunities. But labour unions have said that there is still a long way to go before fair working conditions are achieved.

Ms Singh says that making fashion sustainable is a complicated process and there are no straight answers for the best way to achieve it. "The simple solution would be to produce less but in the end, it's a business with jobs of millions tied into it."

Indian artisans are globally recognised for their craft

Using eco-friendly clothing is also not a silver-bullet solution. Fabrics like recycled polyester and those made from wood pulp have a lower carbon footprint, but they too have an environmental cost as their production could lead to deforestation, Ms Singh says.

The onus, she says, also lies on consumers to make mindful choices.

Things have changed a little after the Covid-19 pandemic with more people becoming mindful of protecting the environment and making sustainable choices, including when it comes to fashion.

The industry has already started responding to this changing trend - FDCI chairperson Sunil Sethi says many designers are choosing to focus on one collection a year instead of seasonal ones. Even celebrities are embracing the idea of pre-loved clothing and repeating outfits.

The process is slow but, he says, every step is a way forward.

Mr Sethi says that designers have also found new ways of defining luxury, where the focus is not on creating more but less.

He calls it "slow luxury", or garments that are crafted by hand, slowly and methodically, to create ensembles that outlive seasonal trends, almost like an heirloom that can be handed down from one generation to another.

That's exactly the sort of fashion that renowned Indian designers Abraham and Thakore are known for.

Called the "quiet revolutionaries" of the fashion world, the designers are credited with reinventing Indian couture by experimenting with eco-friendly fabrics, while staying rooted in traditional textiles and crafts.

"It's simple - short-term trend is just not the solution to anything," Mr Thakore told the BBC.

"When you create something unique and signature, it automatically becomes non-disposable. And it's not just fashion, it applies to everything."

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here, external to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: