Alexei Navalny's life in 'Polar Wolf' remote Arctic penal colony

- Published

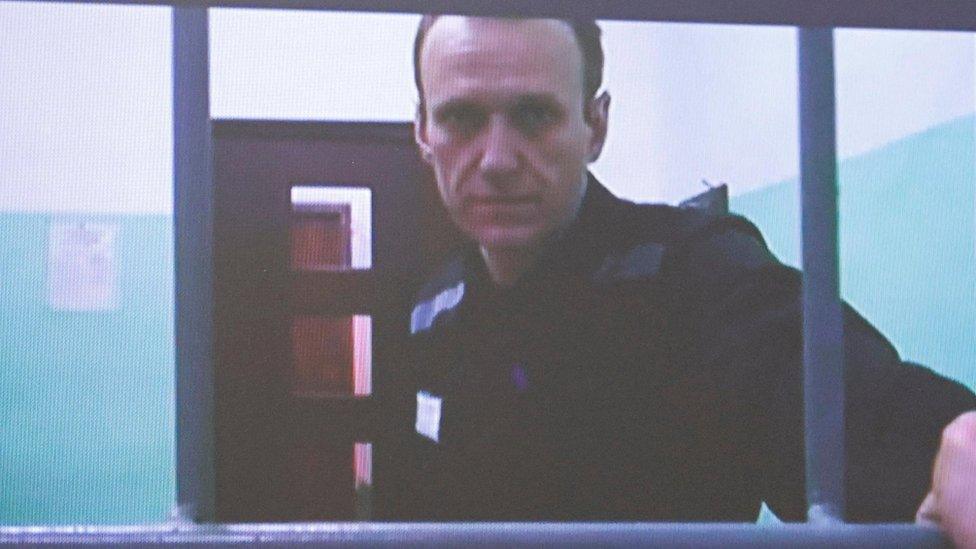

Alexey Navalny had been in jail since February 2021 and arrived at IK-3 in December

Alexei Navalny's penal colony is the strictest penal colony you can get. Only those accused of the very worst crimes are sent to IK-3.

Nicknamed Polar Wolf, it is located in Yamalo-Nenets region, well above the Arctic Circle. Conditions, needless to say, are very harsh.

It is known for a culture of collective punishment and winter temperatures there can go as low as -20C.

Inmates have described being punished for the infringements of others by being made to stand outside in the winter without coats. Those who fail to stand still face being doused with cold water.

Snow covers the ground for months at a time - only to be replaced by muddy slush when temperatures rise above freezing, around May.

In the summer, prisoners are forced to strip to their waists in swarms of mosquitoes.

With summer comes long days with no nights. It all takes a heavy physical toll.

Navalny's day-to-day life will have been a lonely one, since December in IK-3 and before that at the IK-6 facility in Melekhovo, east of Moscow.

Since 2022, he had spent nearly 300 days in in solitary confinement and lately he was allowed one daily stroll in a nearby cell where the floor was covered in snow.

All he could see outside his window was a tall fence, and no light. In winter in the Arctic Circle, it's only ever dusk at best.

With years of jail ahead of him, Navalny had to find ways of remaining relevant.

He filed complaints about prison conditions that would allow him to appear in court and deliver statements on camera on a regular basis. He tried to create a trade union for prisoners to campaign for better seats in the jail's sewing factory.

He made a noise so he wouldn't be forgotten.

Navalny was known for his acerbic wit. He always tried to make light of his situation, no matter how hard the conditions were.

Through social media posts, written and posted by his lawyers, he talked about the conditions he was held in - often with more humour than many thought possible.

He described New Year's Day in the punishment cell, saying: "It goes like any other day: wake-up is at 05:00, bedtime at 21:00. So for the first time since I was six years old, I just slept the entire New Year's Eve. Overall I'm pleased. People pay money to celebrate the New Year in an unusual way, but I did it for free."

But his day-to-day life must have been truly testing.

In January 2023, he wrote about being assigned a new cellmate with severe mental health problems.

"There are many videos online about people who believe that they are possessed by demons and devils," he said.

His cellmate was "very similar" - emitting "a growling, guttural scream that periodically turns on and doesn't turn off for hours. He yells for 14 hours during the day and three hours at night."

A view of penal colony IK-3, where Alexey Navalny had been held since December

On another occasion, he was made to share a cell with a person who had "serious problems" with hygiene.

"If you live in a cell, and some person lives at arm's length from you 24/7, and you are both one or two meters from the toilet 24/7, and the toilet is a hole in the floor, maintaining hygiene is of fundamental importance. And a prisoner who is problematic in this sense will instantly make your life unbearable."

Navalny was sure that neither of his cellmates arrived by accident. He believed they were just another way for the Russian prison system to make life hell for an inmate if they wanted to.

At 47 Navalny wasn't old, but being poisoned with the nerve agent Novichok and spending three weeks in a coma took its toll. Living a life of constant deprivation in jail only added to that.

In December, he said his request to see a dentist had been denied for 18 months.

He had also developed serious back problems, and recently had difficulties walking and standing. One of his legs was going numb, possibly indicating a herniated disk.

Despite his smiles and relaxed air in court, with each appearance he became more gaunt.

In 2023, more than 500 Russian doctors signed an open letter demanding to have him seen by a civilian doctor after he said he had been suffering from a cough and a fever and had to share a cell with an inmate with tuberculosis.

Russian prisons have a long history of torture, both physical and psychological. Inmates are often abused by prisoners friendly to the administration, and rules that are impossible to follow add to the mental anguish.

The federal prison system itself estimates there have been an annual 1,400-2,000 prison deaths over the last five years. The number one cause is invariably put down to cardiac problems.

Lawyers treat this explanation with suspicion. "They can cover up anything as a cardiac arrest - even a suicide or a killing by other inmates or guards," says lawyer Irina Birykova.

In her experience, it's nearly impossible to overcome the hurdles created by the prison system if authorities don't want the cause of death to be independently verified.

Navalny's death has dealt an enormous blow to Russians who saw him as an emblem of resistance.

It was clear he could no longer lead Russia's opposition, but there was an underlying hope that one day the political situation would change and Navalny would be able to come back.

If Vladimir Putin ever needed to negotiate his own freedom or safety, Navalny might have been part of the bargain.

Most Russians now agree there is little hope now in protest. People will try to mark his death in their own way, laying flowers in locations where Navalny stood.

Some brave souls will even come out on to the streets, and they will be punished.

If shock following the Russian invasion of Ukraine failed to bring masses of people on to the streets, Navalny's death won't either.

But privately, a lot of Russians are grieving. For them, this will just be another very dark day and a loss of hope.

Alexei Navalny: More coverage

OBITUARY: Russia's most vociferous Putin critic

BEHIND BARS: Life in notorious 'Polar Wolf' penal colony

IN HIS OWN WORDS: Navalny's dark humour during dark times

SARAH RAINSFORD: Navalny was often asked: 'Do you fear for your life?'

Related topics

- Published16 February 2024

- Published16 February 2024

- Published16 February 2024