Europe's moments of 2013

- Published

- comments

The year saw increasing tensions between the French and German leaders over economic policy

In 2013 there were 12 moments which left their mark with me. It was a year when Europe grew in confidence and dared to believe it could escape its crisis.

1. Merkel dance

In September the German Chancellor Angela Merkel underlined her status as the most powerful politician in Europe. Unlike most leaders of her era she actually increased her support at the polls. Everyone understood it was her victory rather than her party's. At the post-election celebration at Christian Democrat (CDU) headquarters, after she was showered with praise, the music began and for the briefest of moments Angela Merkel danced.

In retrospect it might have been the high water mark of her power. Lacking a governing majority she was forced to begin marathon coalition talks with the Social Democrats (SPD). Much of southern Europe hoped her new coalition partners would help soften her commitment to austerity. Europe waited for a third-term Merkel to define herself.

2. Jobless recovery

One early morning in Lisbon I went to the Angolan Embassy. It was not yet 0800 and there was already a line of 400 people. One of the ironies of Europe's crisis was that thousands of Portuguese workers were heading to their former colonies in search of work.

Many of Europe's best and brightest were on the move. Since the crisis began over 300,000 Greeks have emigrated. 200,000 have left Ireland.

In the Italian city of Pisa the Swedish home furnishings chain Ikea planned to open a new store and advertised for 250 staff. It received 28,816 applications.

The EU's official statistics pointed to a jobless recovery, offering little hope to the 26 million out of work.

3. A protest for Europe - Kiev

Throughout the year polls pointed to growing disenchantment with the European Union.

The bloc seemed incapable of delivering growth and prosperity and the voters were tired of bailouts and austerity.

Yet to the east, in Ukraine, tens of thousands of protesters braved bitter temperatures to declare their future belonged with Europe. It was a reminder that Europe, as before with former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, still could serve as a beacon for democratic values.

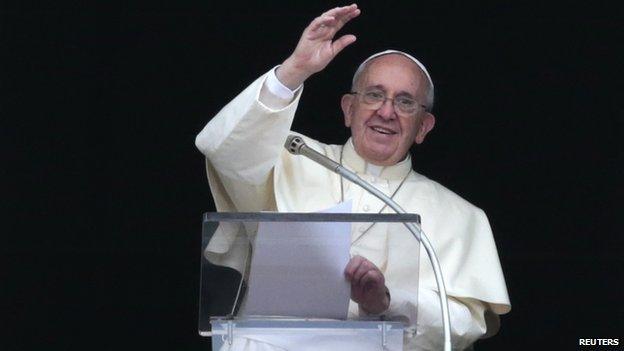

4. Pope and moral authority

In March I was in St Peter's Square when the smoke turned white and the Catholic Church had a new Pope. It was to be caught up in a moment of religious ecstasy as thousands of people surged towards St Peter's Basilica. My producer captured a stunning image of nuns in the rain at full sprint heading for the square.

In a matter of months Pope Francis attracted back some of the thousands who had deserted the Church.

Some of his strongest words were for the rich. "The culture of prosperity deadens us," he said. "Money must serve, not rule!" Europe had a powerful new voice.

The new Pope's gestures of compassion have attracted worldwide comment and raised expectations

5. Budgets and democracy

In November I watched the EU's Economics Commissioner Olli Rehn exercise historic new powers. He delivered his verdict on the budgets of the 17 eurozone countries even before they were approved by national parliaments. So we had the sight of an unelected official declaring fault with Italy's budget before Italian MPs had had their say.

It was a reminder that democracy will have to catch up with the flow of more power to Brussels.

6. Enigma of President Hollande

No leader worried Berlin more than the French president. It was difficult to pass through the German capital without receiving a briefing that Francois Hollande's first 18 months in power had been wasted. His reforms, I was told, had been tepid. France was the country holding the eurozone back and might yet head back into recession. At home the French leader had appeared cautious, indecisive, prone to backing down. His poll ratings were the lowest of any president in the history of the Fifth Republic.

Yet abroad he had acted swiftly. He had deployed French troops in Mali. He was bold over Syria and the use of chemical weapons, insisting that the Syrian regime could not go unpunished. He was prepared to use force against Damascus. When news of widespread killings began emerging from the Central African Republic, Francois Hollande committed French troops again.

In December I attended a routine event addressed by the president. He wears his criticism lightly - at least in public - and that is part of his enigma.

7. Deadly journey to Europe

In early October I stood on the rocks on the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa. Off the coast 360 people, mainly Somalis and Eritreans, had died. Their boat had been so close to land that they must have been able to see the lights of the island. When their engine failed they lit some cloth to attract attention. Instead, the boat caught fire and in the panic it capsized.

The tragedy underlined certain truths - that for hundreds of thousands of Africans Europe remains a promised land; they are prepared to take unimaginable risks to reach its shores and, almost certainly, will not be deterred. They are exploited by ruthless gangs who demand $3,000 (£2,511) for the trip.

Europe's policy towards these migrants is confused. What happens is that, within days, most of those who survive are heading to cities like Stockholm where they are promised residence.

8. Protesters

In Greece there was exhaustion with protest. There were still almost daily strikes and demonstrations but they had lost some of their energy. Greeks clung to the hope that after five years which saw their economy decline by 25% they were turning a corner.

Elsewhere protests gained strength. France witnessed the emergence of "les bonnets rouges" - a protest movement with its roots in Brittany, with its symbol of red hats taken from an earlier tax revolt. They objected to an eco-tax on trucks but their anger reflected a much wider discontent with a stagnant economy.

Italy had its "pitchfork" protests. It drew together students, farmers, business owners in frustration at the failing economy. The Italian president warned of "violent social unrest" and it was a reminder that the eurozone crisis is not over.

9. Bye Bye Silvio

In October I stood outside the Italian Senate and watched the departure of Silvio Berlusconi. He had just gambled and lost. He had tried to bring down the government of Enrico Letta but had been unable to line up his own party behind him. The power of the man who had dominated Italian politics for 20 years was fading.

His face was expressionless as he passed. As his car moved away many among the crowds booed and gave him the thumbs down. Predicting his downfall has often proved rash, but 2013 did seem to mark the end of the Berlusconi period.

10. Quiet diplomacy - Cathy Ashton

Europe since 2009 has had a foreign affairs chief, but few knew it. Baroness Ashton had been given the grand title of High Representative for Foreign Affairs. The job was ill defined and Cathy Ashton was wary of the press. Behind the scenes, however, she worked tirelessly and in November held centre stage when the Iranians agreed to limit their nuclear programme. It was a diplomatic breakthrough. Others had been involved -mainly the Americans- but Cathy Ashton chaired the talks and made the case for dogged, persistent quiet diplomacy.

11. Challenge to 'ever closer union'

Early in 2013 we gathered in Amsterdam for what was billed as a major address by UK Prime Minister David Cameron on the future of Britain and Europe. It was postponed and then delivered in London. He sought an exemption from "ever closer union" and offered an in/out referendum in 2017. He promised to campaign with his "heart and soul" to remain in the EU.

Predictably the speech drew plenty of criticism, but there were references to reform that echoed around Europe. At the end of the year it remained clear that Britain was not alone in demanding reforms to the European project, but Britain was struggling to form alliances for its vision of Europe.

12. Celtic comeback

Finally the Republic of Ireland escaped the rigours of the bailout programme. In November 2010, under pressure, it had accepted a rescue. The country was on the edge of bankruptcy, brought down by taking on the debts of its banks. Ireland knuckled down and slashed spending and cut benefits.

In the end the confidence of the markets returned. It is not quite the return of the Celtic Tiger, but the country proved a magnet for foreign investment, particularly from hi-tech companies. But debt remains high, unemployment is above 12% and emigration has returned.

It reflects the story of Europe in 2013 - signs of progress, but uncertainty whether the eurozone can discover levels of growth that reduce the unemployment lines.

For those who follow this blog I send best wishes for 2014. Early in the New Year I will set out Europe's challenges for the 12 months ahead.