Paris attacks: Key questions after Abaaoud killed

- Published

Mourners have left flowers and messages near the Bataclan concert hall where 89 people died

France and neighbouring countries are on high alert after the Paris attacks, which killed 130 people and wounded hundreds more.

President Francois Hollande says France is "at war" with so-called Islamic State (IS).

For four days Brussels - the Belgian capital and home of EU institutions - has had an unprecedented security lockdown.

Here we look at the international impact of the 13 November attacks and the lessons the authorities are trying to draw from it.

Are the attacks over?

It is too early to say. But there was a breakthrough on 19 November - it was confirmed that the suspected ringleader, IS militant Abdelhamid Abaaoud, was killed in a police raid in Saint-Denis, northern Paris.

His fingerprints were formally identified from remains found in a Saint-Denis apartment where, the previous day, a group of militants had fiercely resisted anti-terror police.

Two others also died there - a cousin of Abaaoud called Hasna Aitboulahcen and a man not yet identified.

France is urgently hunting another leading suspect - Salah Abdeslam, who hired one of the cars used in the attacks. Salah's brother Brahim blew himself up in Boulevard Voltaire on 13 November.

French media reported that nine militants carried out the attacks. Nine militants, including Abaaoud, have now died, but Salah Abdeslam is still on the run.

Belgium has now also issued an international arrest warrant for Mohamed Abrini, 30, suspected of having been in a car with Salah Abdeslam before the attacks.

Police raided this apartment block in Saint Denis - and got into a fierce firefight

Paris prosecutor Francois Molins says there is evidence Abaaoud was planning to attack La Defense - an upmarket Paris business district.

Two men were arrested in the apartment in Saint-Denis and six other people nearby, so police may get some key information from them.

How was the plot hatched?

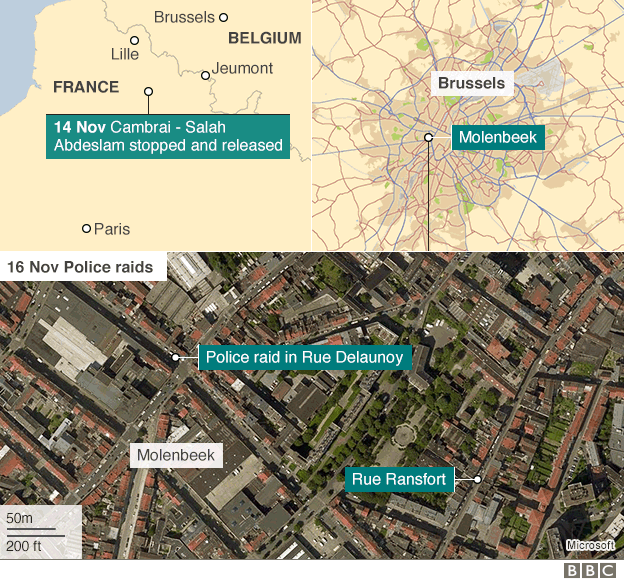

French authorities believe that IS in Syria decided to launch the attacks, and that the operation was planned in Belgium, probably in Molenbeek, a Brussels district known for high unemployment, social problems and a mixed immigrant population.

IS said its militants had attacked Paris in order to punish "crusader" France for its air strikes against "Muslims in the lands of the Caliphate" - their language for Iraq and Syria.

The attack "targeted the capital of prostitution and obscenity, the carrier of the banner of the Cross in Europe: Paris," IS said.

Many Molenbeek residents are Arabs, and jihadists have long been linked to the area.

Belgian police have carried out several searches there since 13 November and charged five suspects in connection with the attacks.

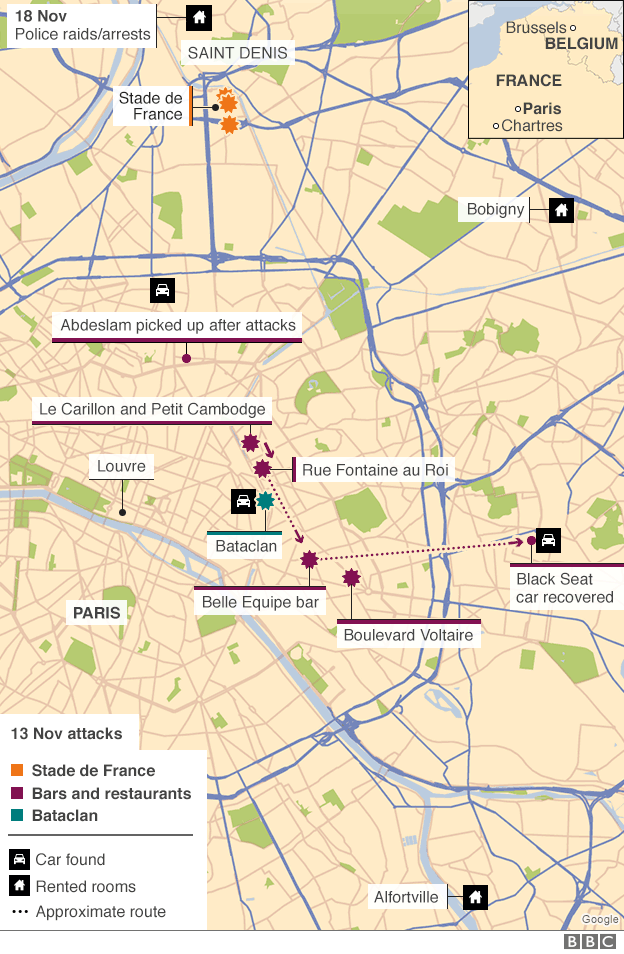

At least three cars hired in Belgium were used in the attacks: a black Seat, a black VW Polo and a VW Golf.

Investigators suspect the gunmen used safe houses in Saint-Denis, Bobigny and Alfortville in the Paris region.

But it is not clear when the group met up to launch the attacks. Other elements of the plot also remain unclear.

Investigators will be studying phone records and assessing the weapons seized for further clues.

Paris attacks and police raids

Investigators believe there were three well-organised, tightly co-ordinated groups of militants involved in the 13 November attack. They used Kalashnikov assault rifles and explosive belts.

The militants - four of them French citizens - struck at three main locations: outside the Stade de France and, in central Paris, crowded bars and restaurants and the Bataclan concert hall.

Three detonated their suicide belts near the stadium, during a high profile France v Germany football match. They may have planned to get inside the stadium but been frustrated.

The Bataclan concert hall was the bloodiest scene - 89 people died there.

The attacks probably required months of training, said Pieter Van Ostaeyen, a Belgian expert on Islamist extremists.

The plan was evidently designed to kill many people randomly - they targeted crowded places, where young people were having fun.

Why weren't the attackers stopped?

France's security services and its European partners will be scrutinised as to whether they should have picked up intelligence about the attacks, and stopped them.

For example, two Belgian IS fighters had warned in a video in February that they would attack France, Mr Van Ostaeyen told the BBC.

And security was stepped up in France after the January Islamist attacks in Paris on Charlie Hebdo magazine staff, a policewoman and a Jewish supermarket. Three gunmen killed 17 people before being shot dead by police.

But security experts say it is very difficult to prevent attacks like the latest Paris one, involving groups of suicidal gunmen with bombs hitting soft targets indiscriminately and simultaneously.

There is surveillance of known jihadists' communications - whether via mobile phone or the internet - but, increasingly, widely available strong encryption makes that more difficult.

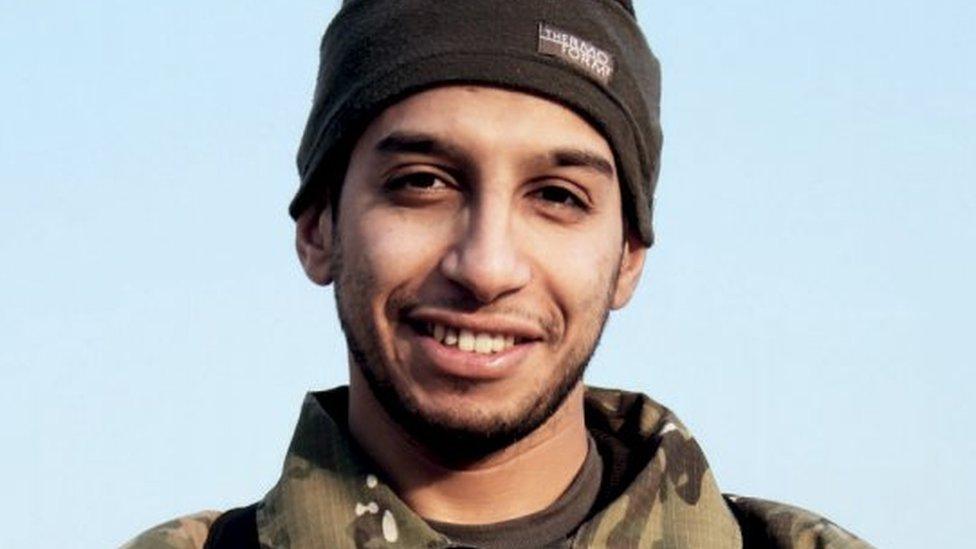

In February the IS online magazine Dabiq identified this man as Abaaoud

France and Belgium are now tightening monitoring of suspected jihadists, because some of the attackers had spent time in Syria with IS jihadists.

Among the proposals are: jail or house arrest for jihadists who return from Syria; stripping violent jihadists of their citizenship; putting electronic tags on suspects.

Some critics also say it is far too easy for jihadists to cross borders in the EU's passport-free Schengen zone. Only now are vehicles being routinely checked at the Belgium-France border.

More intelligence-sharing might have alerted police to the imminent threat to Paris.

How significant is the Belgian connection?

Very - Molenbeek was apparently the operational nerve centre, but there were some other Belgian connections.

Abaaoud boasted of having helped set up an IS cell in Verviers, eastern Belgium. Police raided a safe house there in January, killing two jihadists, but he got away.

Belgian ministers admit that more should have been done to tackle Islamist extremism in Molenbeek.

Police have stepped up searches and patrols in Molenbeek - suspected nerve centre of the jihadists

Mehdi Nemmouche, a Franco-Algerian jihadist accused of murdering four people at the Jewish Museum in Brussels in May 2014, had also spent time in Molenbeek.

More jihadists have gone from Belgium to join IS in Syria and Iraq than from any other EU country, per capita.

Belgium - highly federalised - has various police forces, so sometimes co-ordination is a problem.

Sometimes key intelligence is not passed on - not only inside Belgium but also to EU partners such as France, says Dutch expert Liesbeth van der Heide, of Leiden University's Centre for Terrorism and Counterterrorism.

The EU does not have a central database for specific intelligence on jihadists - but there are calls for that now.

Has Europe lost control of its borders?

The Paris bloodshed has fuelled concerns about Schengen and the EU's external borders.

Freedom of movement is a cherished core value of the EU - but it means that violent jihadists and other criminals can also cross borders easily, after entering the EU.

Schengen exists in a Europe where national authorities still jealously guard intelligence that affects their country's security.

On entering Schengen, EU citizens' passports are generally checked just for validity and authenticity, but not routinely checked with police database records. EU governments have decided that such checks will be routine in future.

Lesbos: Thousands of migrants are still arriving daily on the Greek islands near Turkey

As for the EU's external borders, the influx of migrants - many of them Syrian refugees - has put them under severe pressure this year.

Greece and Italy, with long sea borders to patrol, are getting help from the EU to screen arriving migrants. But it is not enough.

More than 650,000 migrants have reached Europe's shores this year. There are fears that some jihadists have slipped through in the crowds.

One Paris suicide bomber had a fake Syrian passport in the name of "Ahmad al-Mohammed". Greek officials said someone with that passport had been registered last month on the island of Leros.

Later, France found that a second Stade de France bomber had also slipped through Greece posing as a migrant.

Will there be a repeat of the Paris attacks in France or elsewhere?

Under the existing state of emergency, French police have greater powers to search premises and detain suspects.

France has declared a state of emergency following the attacks on Paris

France has also hit back, bombing IS militants in Syria and Iraq. The US and its allies, as well as Russia, are also attacking IS to varying degrees.

So the risk of IS trying to carry out more attacks, inside Europe or elsewhere, remains real.

France has warned that IS might use a chemical or biological weapon in a future attack. French emergency teams are to be supplied with atropine sulfate, an antidote to nerve gas.