Italy earthquake: Life after L'Aquila's heart was ripped out

- Published

The climb down to the 'smart tunnel' of L'Aquila

Central Italy's devastating earthquake of 24 August will rumble on in the lives of survivors for many years - that is the all-too-painful lesson of the town of L'Aquila.

On 6 April 2009, a magnitude 6.3 earthquake killed 309 people, wrecking L'Aquila's medieval heart.

Every day a man leaves his flat in the suburb of Sant'Antonio and comes into the town centre to visit his old house, now an abandoned building.

The cats eat on the doorstep

He brings food for his two cats and his dog, who have lived there since 2009. The quake made 58,000 people homeless.

The man cannot very well keep his pets at his small, newly-built flat. So they stay on, the cats on the doorstep, the dog inside behind the door, with a garden to roam in.

One day the old house may be restored or rebuilt, but for now that area remains a massive building site.

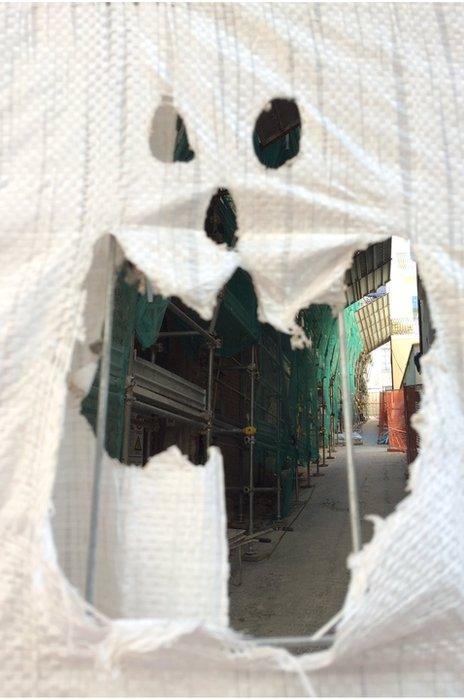

It really only comes alive at night when students throng shiny new cafes, strutting along rubble-free streets, kissing between pillars against a backdrop of vast, spectral tarpaulins and curtains of scaffolding.

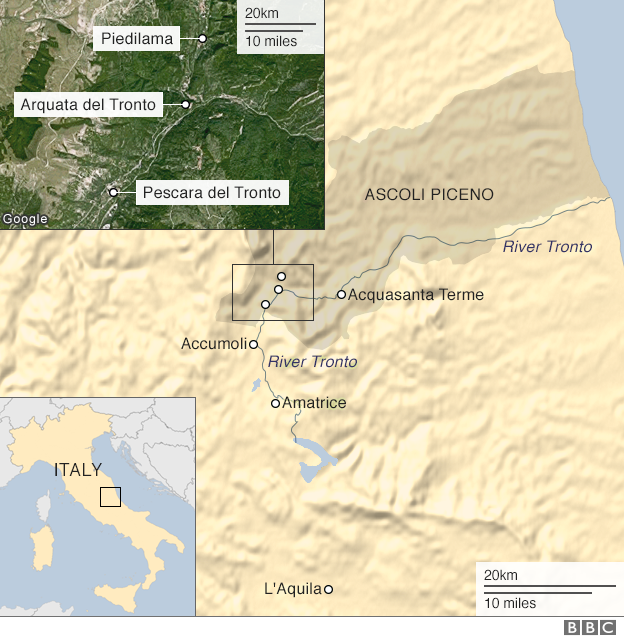

L'Aquila is about 50km (30 miles) south of the latest earthquake zone, which is centred on Amatrice.

Did they feel the new quake in L'Aquila?

When the Earth shook again this August, music archivist Luca de Paolis and his family jumped out of their beds and rushed to the car in the night, like other residents of L'Aquila.

They drove to a car park and waited for the damage reports, knowing only too well what to expect.

The 2009 quake felt like being inside a milkshake mixer, Luca recalls. He and his wife and two children were unhurt and the family home in Sant'Antonio survived intact, apart from a few superficial cracks, but the emotional stress carried on.

They all remember how the fur on the muzzle of their pet dog, a beloved Italian Volpino called Trillo, dropped out and it developed a bad heart, dying prematurely a few years later.

What was lost seven years ago?

"We lost our town," is how one woman puts it. She and her husband had to abandon their flat in the old town.

The apartment block is today a shattered hulk with broken windows, too dangerous to enter.

Simone remembers a very different town

Luca de Paolis with his new dog Atos

To date, 632 buildings have been demolished and 1.6m cubic metres of rubble removed. Less tangible is the damage to the social fabric.

"Before the earthquake, we would always go with friends to places in the town centre," says Luca's son Simone, 26, a comic book artist.

"You can go there now but the texture is gone. Pubs open and close again after a few months because they don't get the customers."

Christmas shopping these days largely means a new suburban mall, he says.

"Before the earthquake, L'Aquila was a small town with everything you wanted," adds family friend Olivier Agnelli, 20, who studies mechanical engineering in Turin.

"Since the earthquake, it has nothing. It is difficult to restart life without a centre or a bar where you can go with your friends. Small businesses like grocery stores, bars and restaurants disappeared."

What is being done?

The town authorities are determined to rebuild, but the planning challenge is enormous, never mind bureaucracy and suspicions of corruption in the construction industry.

It is one thing to demolish and rebuild modern housing, as has been done in parts of L'Aquila, but quite another to restore or rebuild in an area densely packed with historic buildings.

A face cut out of a builder's sheet exposes a ruined street in L'Aquila

As of March, the authorities had spent €4.4bn (£3.8bn; $4.9bn) on reconstruction in the private sector.

New out-of-town estates were built for 10,887 people whose homes cannot yet be restored, while the rest returned to rebuilt flats on the outskirts or moved elsewhere.

In the most striking new project, a high-tech "smart tunnel" is being dug under the old town to supply the population with water, sewers, power and communications at a cost of €80m.

The population has been gradually returning to its pre-quake level: it was recorded as 70,230 in 2014, compared to 72,696 in 2009.

The joke from the first years after the disaster that L'Aquila would become the new Pompeii has worn thin, just as the number of "rubble tourists" seems to be dwindling along with the rubble itself.

On estates like Sant'Antonio, where the flats are built on anti-seismic columns, people live in hope that one day they will be able to move back to a town centre, lovingly and safely restored.

"Italy is a beautiful country," says an elderly man I meet on a bench there. Then he smiles and adds, "but that can change all of a sudden".

- Published30 September 2016

- Published29 September 2016

- Published25 August 2016

- Published27 August 2016