Does Hitler's legacy still cast shadow over the world?

- Published

The fate of the building in which Hitler was born in 1889 has long been a contentious issue

A pale lemon building in a pretty Austrian town awaits its fate, victim of evil's long shadow.

The 17th century inn at number 15 Salzburger Vorstadt in the border town of Braunau am Inn is where Hitler was born 127 years ago.

The Austrian government has said it will either be torn down or restructured to stop neo-Nazis turning it into a shrine.

It seems a bit late.

Hitler cannot be forgotten. But how he is remembered is important.

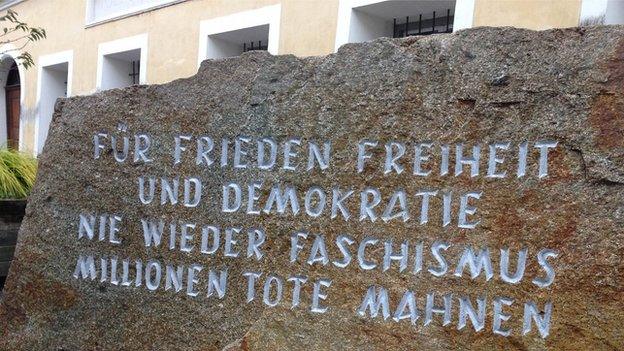

The stone plaque outside Hitler's birthplace which honours the victims of fascism

There is a memorial stone outside the inn with the inscription "For peace, democracy and freedom. Millions of dead remind us - never again Fascism".

Should we turn our face away from Hitler's history or wonder that this monster still casts such a long shadow? Is it perhaps not a shadow but a light, a potentially useful illumination of our own times?

Is it helpful or pointless that his memory is used to inform opinions about the rise of the hard right, the growth of Russian nationalism, Dutch politician Geert Wilders and the success of Donald Trump?

It may be worrying that we would rather ignore history than listen soberly to what it tells us. So I am going to ignore one clear lesson - sensible politicians and journalists should never mention Hitler.

Hitler exerts a huge fascination over us, a tremendous revulsion, which is sometimes so strong that it obscures valuable lessons.

"Nazi!" has become a cheap insult, as devalued and meaningless as shouting any other four-letter word.

But abuse should not prevent insight.

The Austrian government fears that Nazi sympathisers could make his birthplace into a focal point

This icon of evil was an astonishingly successful politician. His deeds were so monstrous that other political mass murderers are shoved into the shadows.

Indeed that whole debate has spawned a cottage industry comparing the crimes of Mao and Stalin and asking why the National Socialist leader evokes more horror and outrage.

The Austrian authorities seemed to be worried by the most obvious and least important legacy of Hitler - the fan club.

There are of course small groups all over Europe - from Sweden, external to Cambridge, external - who revere Hitler, but in general there is little appetite in Europe for uniforms, marching men and enthusiasm for war.

AfD leader Frauke Petry has been criticised for trying to revive the Nazi-era word "voelkisch" ("people's" or "national")

The echoes are more subtle than that. There is clearly a growing attraction in solutions outside the mainstream, particularly on the nationalist, anti-immigration right, many of whom have a strong sense of cultural and ethnic identity.

Most European countries have seen a rapid growth in such parties - all with different flavours but united in their populism.

Hitler was not the first populist but he was a remarkably successful exponent of the brand.

At its core, populism attacks unpopular out groups - "the other" - via the criticism of elites, who are accused of cosseting or protecting such groups and betraying "the people".

Theresa May faced some criticism for rejecting those who considered themselves "citizens of the world" in her conference speech

Hitler claimed to have a quasi-mystical insight into the will of the German Volk (people) and the leaders of modern right-wing movements make much of similar personal interpretations of their personal electorate's desires.

The long shadow of Hitler makes some shiver at verbal echoes - even unintentional ones.

It is why talk of a "list of foreigners" at the Conservative Party conference makes some think of the Nuremberg Laws., external

It is why when Theresa May says, "If you believe you're a citizen of the world, you're a citizen of nowhere", some think about the unpatriotic "rootless cosmopolitans" derided by Hitler (and Stalin) as antithetical to pure-blooded nationalism.

It makes even the vague suggestion of looking at migrant children's teeth before they are put on trains a symbolic nightmare, despite the Home Office's rejection of the proposal.

But you have to look beyond the EU's borders for the politician most compared to Hitler.

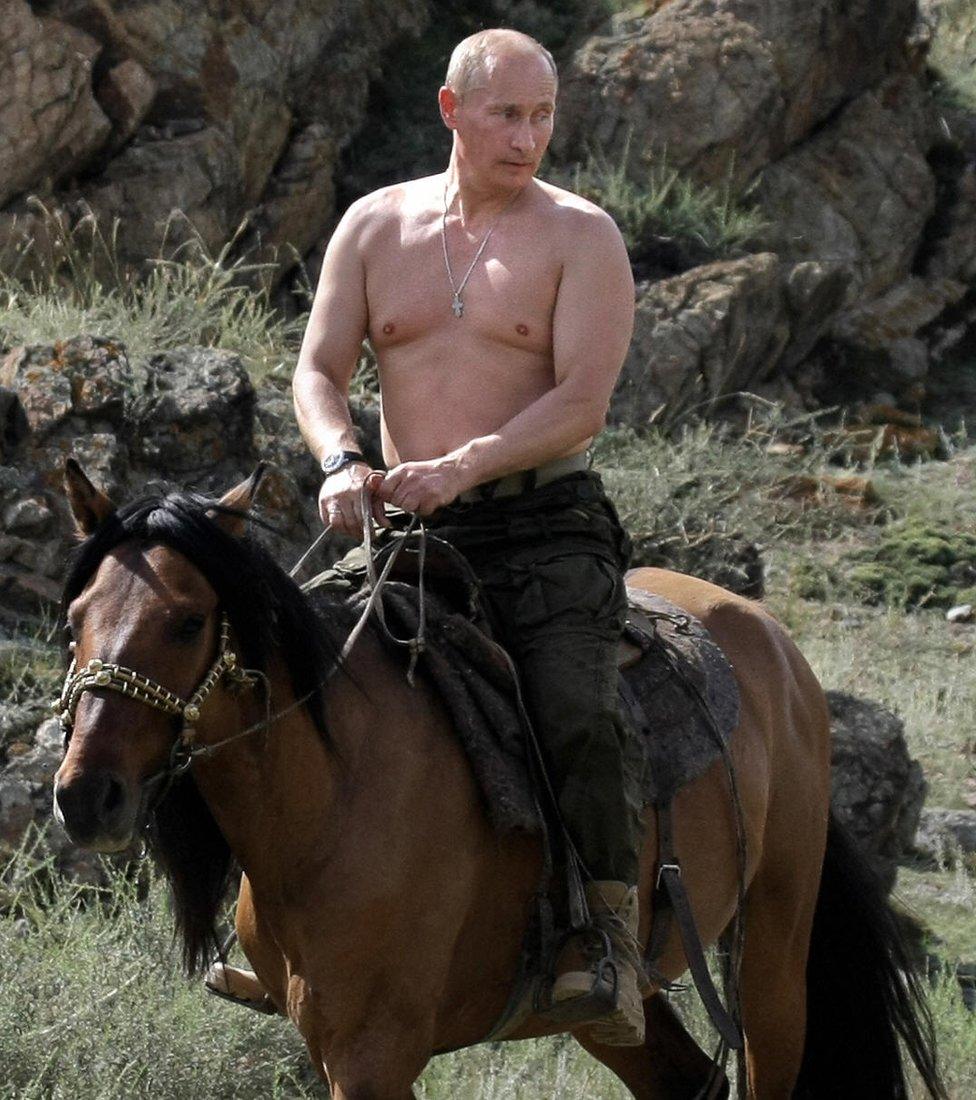

It is Russian President Vladimir Putin, not for his hyper-macho nationalism, external but his foreign policy. Despite the protestations, external from his defenders, this is more than vulgar abuse.

Hillary Clinton, external, David Cameron, external and Prince Charles, external have all made the point that Hitler occupied Czechoslovakia using the excuse of the treatment of ethnic Germans, while Putin cited the fate of ethnic Russians in Ukraine and Crimea to justify military involvement., external

Hillary Clinton and David Cameron have both compared some of Russian President Vladimir Putin's actions to Hitler

Here Hitler casts an intriguing shadow. The simple lesson might be that only actually military action deters such an aggressor., external But it hasn't happened. It is interesting Putin's defenders draw different conclusions from the shadow - this, they say, is what happens when a wounded, once great Empire is treated like a pariah., external

Disingenuous perhaps, but what is interesting is that those Western politicians making the Hitler comparison don't seem to be drawing that conclusion in policy terms. Like their predecessors in the 1930s, the prospect of conflict is too horrific to risk. So here perhaps all the shadow illuminates is a sense of impotence.

Then there's something else about the Great Dictator. The man who nearly ruled the world was for a time a figure of fun. So when I turn to Donald Trump to look at lessons from the long shadow, it is nothing to do with immigration or nationalism or casting him as a horror.

It is about underestimation and overestimation.

At every single stage of Hitler's journey to power, the wise commentators declared the voyage was over - the charismatic parvenu had overreached himself.

Even on the eve of his elevation to German chancellor, Hitler was derided as an unsophisticated, unskilled demagogue who had come as far as he would go. Fellow (non-Nazi) nationalists and the establishment felt, given an hour in power, the ranting charmer would be shackled by the bureaucrats.

The implication was that he could whip the stupid masses into a frenzy, but that the grown-ups would control him.

Similarly the disdain of the American media and mainstream politicians has led them to miscalculate Trump's appeal, staying power and his raw skill.

Trump has consistently defied his critics' expectations

The Republican party is obviously split. There are plenty who think they could gag a triumphant Trump, which is not to say, I emphasise again, that Trump would be a Hitler in power.

But those Republicans or establishment figures who think he would be a biddable beast of burden for their policies might need to think again.

And this brings me to a second comparison.

Hitler was a politician of the will, full of grandiose commitments and few detailed policies. His core was a commitment to make Germany great again, in the parlance of our day, to "take back his country". Detailed policy of how this would happen was rarely expounded even where it existed.

The point is this - it was the transformative nature of his own character that would ensure the deed was done. Similarly, as set out in detail here., external Trump depends on trumpeting Trump, to trump any other card. His deal-making, his businesses, his multi-million dollar success story are the guarantee and the promise.

After all the revelations it may sound odd to say that Trump relies on his personality to persuade, but he does. He himself is the charismatic philosopher's stone which can transform base metal into gold.

The message? Still don't underestimate the Donald.

Three very different propositions blighted or spotlighted by Hitler's long shadow. We all agree we should learn from history. It is hard not to be haunted by it.

Mark Mardell presents The World This Weekend on BBC Radio 4 on Sundays at 13:00 or you can listen online.

- Published18 October 2016

- Published12 July 2016

- Published30 April 2016

- Published29 December 2014

- Published10 March 2013