Enda Kenny: From bust to boom to Brexit

- Published

Enda Kenny served two terms as taoiseach from 2011 to 2016

Enda Kenny came to power at a time of great uncertainty for the Republic of Ireland and Europe as a whole.

He was elected taoiseach (Irish prime minister) in 2011, four months after the state was forced into a humiliating international financial bailout.

Despite having helped to steady the ship, navigating a path from crippling debt to economic recovery, it was not enough to prevent a slow mutiny.

He leaves the helm with new storms on the horizon - the biggest being Brexit.

The UK's exit from the European Union and the collapse of devolved government in Northern Ireland are just two of the challenges he hands on to his successor.

It is not the legacy nor the timescale he would have chosen, but Mr Kenny has dealt with his fair share of inherited problems.

He grew up in County Mayo, as the son of a Fine Gael politician who was a member of Dáil Éireann (Irish parliament).

A fresh-faced Enda Kenny was interviewed by RTÉ News when he was first elected to the Dáil in 1975

Having trained as a teacher, Mr Kenny was 24 when he followed his father into politics.

He won the Mayo West seat vacated when his father died in 1975, and has successfully defended it over the last 42 years.

Mr Kenny was a month short of his 60th birthday when he was first elected taoiseach (prime minister) on 9 March 2011.

Fine Gael swept to power with a landslide election victory, as Irish voters vented their anger at being forced to pay for the collapse of the Irish banking system.

The new taoiseach formed a coalition with the Labour Party and the new government introduced a series of unpopular austerity measures.

New taxes and swingeing cuts to public services, pay and benefits are never exactly vote winners, but the most controversial policy was water charges.

Charging households for tap water was a condition imposed on Mr Kenny's predecessors under the terms of the 2010 bailout.

But after years of austerity, simmering public anger reached boiling point over water bills, and thousands regularly took to the streets to protest.

Anti-water charges protests took place in towns and cities across the Republic of Ireland from 2014 to 2016

In December 2013, the Republic of Ireland became the first bailed-out eurozone member to exit its financial rescue programme.

Mr Kenny insisted the years of "huge sacrifice" were paying off, saying his country owed its economic recovery to its workers.

The Republic was once again vying for the title of the fastest growing economy in the eurozone, but Mr Kenny acknowledged too few citizens had benefitted from the recovery.

Although dealing with the "economic emergency" defined much of his career as taoiseach, it was also marked by passionate debates over abortion, same-sex marriage and the legacy of institutional child abuse.

Just a few months into the job, he launched an unprecedented attack on the Vatican for failing to protect children from paedophile priests.

Reacting to the Cloyne Report into clerical abuse, Mr Kenny said: "The rape and torture of children were downplayed or 'managed' to uphold instead the primacy of the institution, its power, standing and reputation."

Enda Kenny on "dysfunction, disconnection and elitism" of Catholic Church

The charge was angrily rejected by the Vatican, and diplomatic ties remained frosty until the election of Pope Francis two years later.

In 2012, the death of a young pregnant woman, Savita Halappanavar, made headlines around the world and reignited debate about Irish abortion laws.

The 31-year-old dentist was refused an abortion while she was miscarrying her first child in a Galway hospital, and died days later from septicaemia.

Savita Halappanavar died after a miscarriage in University Hospital in Galway in October 2012

A public outcry led Mr Kenny's government to quickly reform the law - the 2013 Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act legalised abortion in very limited circumstances.

Two years later, the Republic of Ireland became the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage through a popular vote.

Mr Kenny welcomed the result of the referendum, saying the Republic of Ireland was a "small country with a big message for equality" around the world.

Thousands celebrated at Dublin Castle when the same-sex marriage vote passed by 62%

But despite a seismic shift in attitudes to human rights and human relationships, skeletons of Catholic Ireland's past would continue to haunt his government.

In March 2017, it was confirmed that "significant quantities" of human remains had been found in a mass grave at a former mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway.

The home for unmarried mothers was run by nuns between 1925 and 1961, and high infant mortality and disease were features of such institutions.

The taoiseach described the discovery as "truly appalling" and said the infants buried in unmarked graves had been treated like "some kind of sub-species".

Mr Kenny, who was born in 1951, is a practising Catholic who is married with three adult children.

Mr Kenny and his wife, Fionnuala, met Pope Francis in November 2016

He was 41 when he wed Fionnuala O'Kelly in 1992.

She had been a press officer for Fine Gael's biggest rival and old Civil War enemy - Fianna Fáil.

Last year, it seemed Mr Kenny could be the first man in a century to lead Fine Gael into a once unthinkable coalition with its former foe.

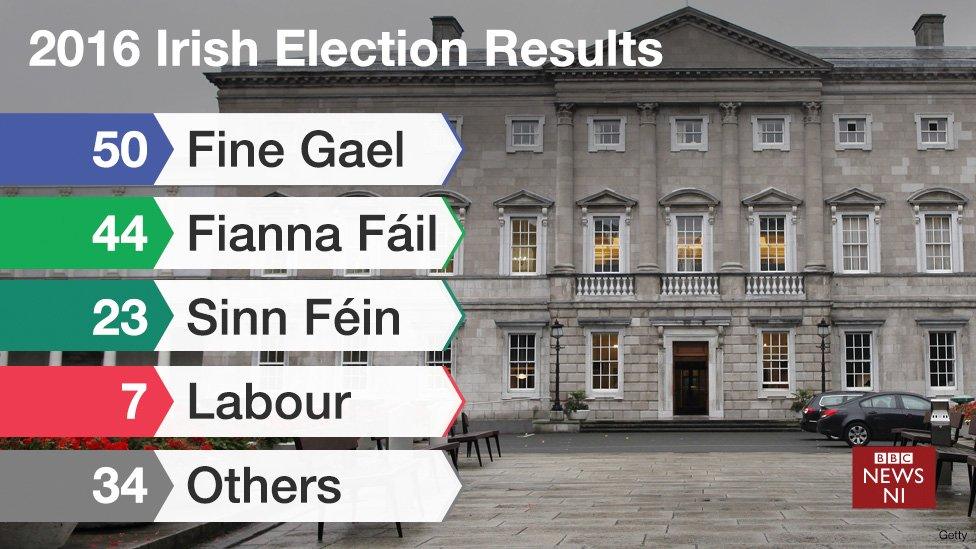

The 2016 general election produced a hung Dáil in which no party won enough seats to govern independently.

Fine Gael held the most seats, but it took four attempts over 70 days for parties to agree who would run the country.

Eventually, on 6 May 2016, Mr Kenny was re-elected to lead a minority Fine Gael government, propped up by independent parliamentarians.

He became the only Fine Gael taoiseach to be re-elected for a second term of government and the party hailed him as the most successful leader in its history, external.

But the honeymoon was short-lived and within months, Mr Kenny was facing opposition from within his own ranks.

His leadership was undermined by a series of scandals involving the Garda Síochána (Irish police force).

Garda Commissioner Nóirín O'Sullivan faced calls to resign after a series of corruption scandals involving her force

The controversy began when two whistleblowers made allegations of corruption over how officers were recording motoring offences.

The bitter dispute escalated, costing the jobs of former Justice Minister Alan Shatter and former Garda Commissioner Martin Callinan.

The current Garda Commissioner, Nóirín O'Sullivan, also faced calls to resign after fresh allegations that senior officers tried to smear one of the whistleblowers with false allegations of child abuse.

Ambitious Fine Gael ministers reportedly demanded the embattled taoiseach set out his timeframe for stepping down.

Mr Kenny resisted, saying his priorities were dealing with the fall-out from Brexit and the growing crisis in the Northern Ireland peace process.

Enda Kenny was photographed under a portrait of Irish revolutionary leader turned politician, Michael Collins, on his first day in office in 2011

Stormont's devolved government collapsed in January over a green energy scandal, adding fuel to the fire of the already complicated Brexit negotiations.

The taoiseach had campaigned against Brexit, warning it would create "serious difficulties" for Northern Ireland and border areas.

After the UK voted to leave the EU, he was criticised for raising the possibility of a future poll on a united Ireland.

Mr Kenny's leadership had begun with a high-point in Anglo-Irish relations - the first visit of Queen Elizabeth to the Republic of Ireland.

But he leaves office at a time full of diplomatic dilemmas over how his country will share a future EU border with its nearest neighbour.

The many, many questions over trade, travel, and territorial claims will now pass to his successor to try to resolve.

- Published6 May 2017

- Published11 March 2016

- Published9 March 2011

- Published15 December 2013