'Lost' film predicting rise of Nazism returns to screen

- Published

The silent film shows Jewish characters being abused in the street and forced from their homes. Credit: Filmarchiv Austria

A silent film from 1924 predicting the rise of Nazism was found in a Paris flea market in 2015 after being lost for decades. Thanks to a huge fundraising campaign, it has now been restored and returned to cinemas, reports the BBC's Bethany Bell in Vienna.

An Orthodox Jew is set upon by three taunting men.

A woman shopping at a market stall becomes outraged at the high prices. She starts pelting a passing Jewish man with fruit.

Later, huge protesting crowds gather outside the chancellor's office. Inside, the leader consults with an adviser. "It is awful to expel the Jews," he says. "But one must satisfy the people."

The incidents portrayed in the Austrian film The City Without Jews (Die Stadt Ohne Juden) are eerily prophetic.

It was made nearly 20 years before the Holocaust, at a time when the Nazi party was banned in Austria, and when Adolf Hitler was in jail in Germany, working on his book Mein Kampf.

'Growing anti-Semitism'

The film tells the story of a city that expels all of its Jews. They are made the scapegoats for rising prices and unemployment.

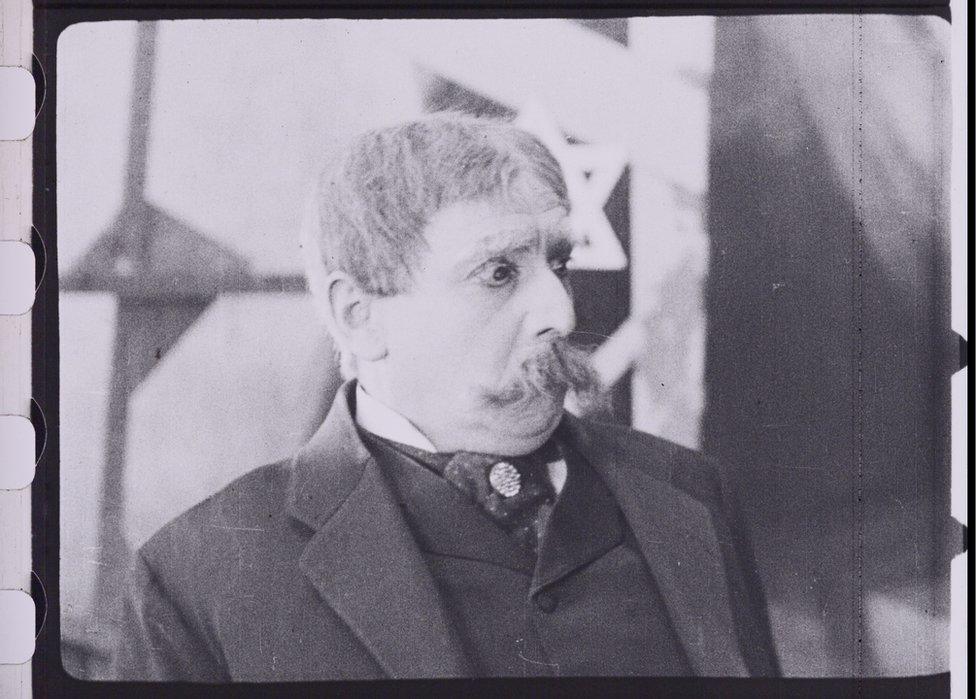

The book and film aimed to combat intolerance

It is based on a dystopian, satirical novel by the Austrian Jewish writer and journalist, Hugo Bettauer.

"At the beginning of the 1920s, just after Austria's First Republic was founded, political anti-Semitism was growing incredibly, much more than during the monarchy," says Nikolaus Wostry, director of collections at the Filmarchiv Austria.

Bettauer was trying to combat rising intolerance and racism, at a time when Jews displaced after World War One were arriving in Vienna.

"Hugo Bettauer was a person who really tried to make society more tolerant - towards Jews, towards homosexuals, toward women taking part in political life," says Mr Wostry.

"That all brought him into big conflicts with the right wing in Austrian society, which was quite dominant at that time."

'Grotesque' murder

Adapted for the screen by Austrian director HK Breslauer, the City Without Jews premiered in Vienna in 1924.

The film was a success, screened in the five biggest cinemas in Vienna, Mr Wostry says.

"But then the political right reacted against it."

Anti-Semitism in Austria was growing at the time the film was made

Less than a year after the film was made, Hugo Bettauer was killed by a Nazi, called Otto Rothstock, following a hate campaign against him.

"His private address was published and in the newspapers, it was explicitly said that such a person shouldn't be part of society."

Mr Wostry says the court case against Rothstock was "grotesque". The murderer escaped with a very short sentence.

Desperate goodbyes

Watching it now, the film's scenes of the expulsion are some of the most haunting and prescient.

The city's Jews are told to leave by Christmas Day. Some of the poorer people leave on foot, accompanied by soldiers with bayonets. Whole communities walk slowly through the snow, some on crutches, some carrying Torah scrolls from the synagogues.

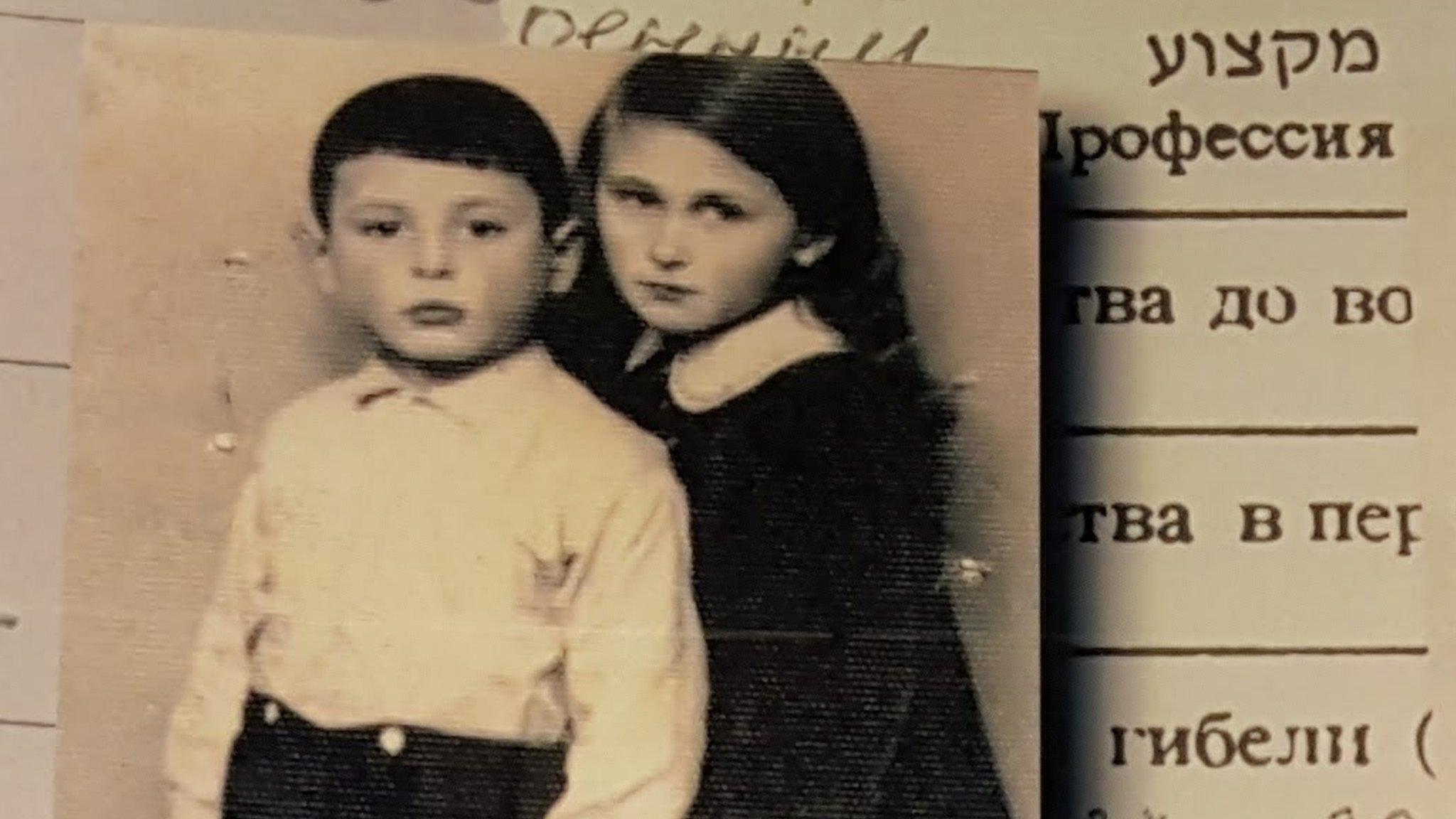

Others leave by train. Desperate goodbyes take place on the platforms. A Jewish father embraces his little daughter, who is staying behind with her Christian mother.

Families are forced to separate as Jews are expelled in the fictional imagining

In reality, some six million Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe were rounded up and killed in the Holocaust. Many others fled abroad.

One of the actors in the film, Hans Moser, one of Austria's most famous film stars at the time, was married to a Jewish woman.

When the Nazis took over in 1938, he refused to divorce her, writing personally to Adolf Hitler, who was one of his biggest fans, asking for clemency.

She eventually emigrated to Hungary and they were reunited after the war.

Meanwhile, the film itself went missing as silent films fell from favour.

"At the end of the silent period, silent films couldn't be distributed any longer and the only way to make a profit was to destroy them and to take the silver, to use the plastic," says Mr Wostry.

"Worldwide 90% of our silent film heritage is lost."

'Growing relevance'

An incomplete and very damaged version was found in the Netherlands in 1991. Then in 2015, the whole film was rediscovered by a collector in a flea-market in Paris.

The Austrian Film Archive organised a crowd-funding campaign to save it. More than 700 people contributed more than €86,000 (£72,000; $107,000) to it. The film has now been digitally restored and re-released.

Nikolaus Wostry says the movie should be considered "one of the strongest anti-Nazi-statements of the silent film period"

It is being screened in Vienna before going on a tour around Austria and reaching European cities including London later this year, where audiences will be able to watch it accompanied by a new score performed live.

Nikolaus Wostry says the movie should be considered "one of the strongest anti-Nazi-statements of the silent film period".

In the film, after the Jews leave, the city celebrates with fireworks. But life soon gets worse. International trade and the economy suffer, and the city's beloved cafes get turned into simple beer halls.

The chancellor eventually invites the Jews back home. Lovers and mixed Christian and Jewish families are reunited.

"It is a statement against excluding people on the grounds of their religion or race from society and has in this respect a growing relevance again for our time," says Mr Wostry.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published28 March 2018

- Published4 January 2018

- Published1 December 2017

- Published10 March 2013