Eta: Basque group disbands but leaves deep wounds for Spain

- Published

More than half Eta's 800 victims were members of Spain's Civil Guard

For Spain this is the end of an era. Separatist group Eta has formally announced it is disbanding, almost exactly 50 years after claiming its first victim.

A ceremony is set to take place later this week in the town of Cambo-les-Bains, in south-west France.

But in a letter to Basque organisations, published by El Diario website and dated 16 April, the militant group writes of "a new opportunity definitively to end the cycle of conflict" and acknowledges the "suffering caused as a result of its struggle".

While Eta's days may be over, nearly half the killings attributed to the organisation have still not been fully investigated. There are many Basques, on both sides, who believe there are still issues to be resolved before true peace can be established.

Eta's decades of violence

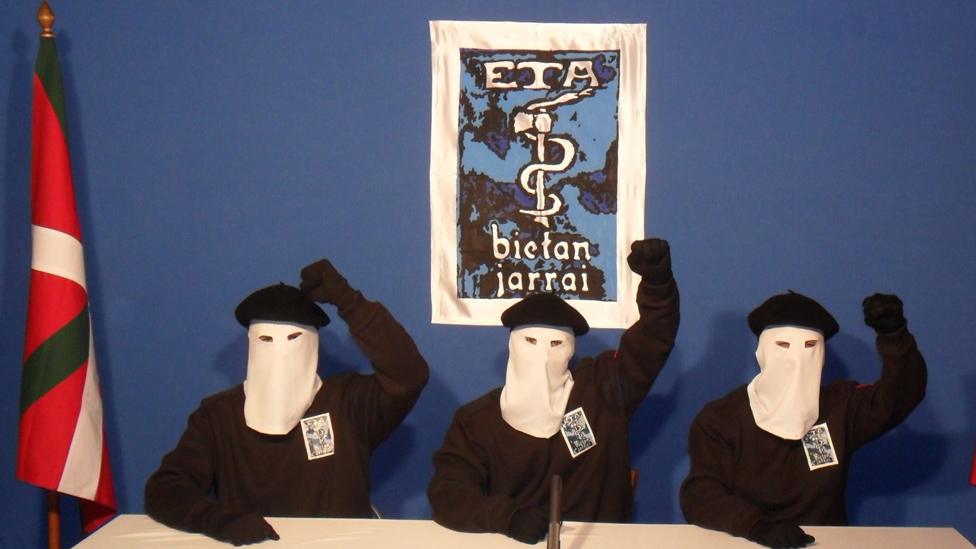

Eta, deemed a terrorist organisation by the European Union, killed more than 800 people between 1968 and 2010, the year before it announced a permanent ceasefire. In April 2017 it staged a disarmament ceremony in the south of France.

The majority of attacks took place in the Basque region of northern Spain and neighbouring Navarre.

A total of 443 civil guards and police died at Eta's hands, according to Europa Press news agency, which reported that 58 businesspeople and 39 politicians were also among its victims.

In its letter, Eta says "years of confrontation have left deep wounds and we have to give them the chance to heal. Some are still bleeding, because the suffering is not in the past".

The terrorism victims' group Dignidad y Justicia (Dignity and Justice) says that nearly 400 deaths caused by Eta remain unresolved and it has called on the authorities to reopen the cases.

"For us there will be no end of Eta as long as there is not justice for all," the president of Dignidad y Justicia, Daniel Portero, told the European Parliament last year.

Eta disarmed in 2017, six years after declaring a ceasefire

Several dozen Spanish intellectuals and relatives of victims of Eta have presented a petition on Change.org, external calling on the group to offer information about its unresolved crimes and criticising what the signatories called its attempts to "whitewash" its crimes.

Why Eta also has grievances

Those who have shared Eta's ambition of an independent Basque state also complain of open wounds.

A report commissioned last year by the region's government, which is led by the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), documented over 4,000 alleged cases of torture by the security forces in relation to Eta between 1960 and 2014. Only 20 torture cases have seen court sentences.

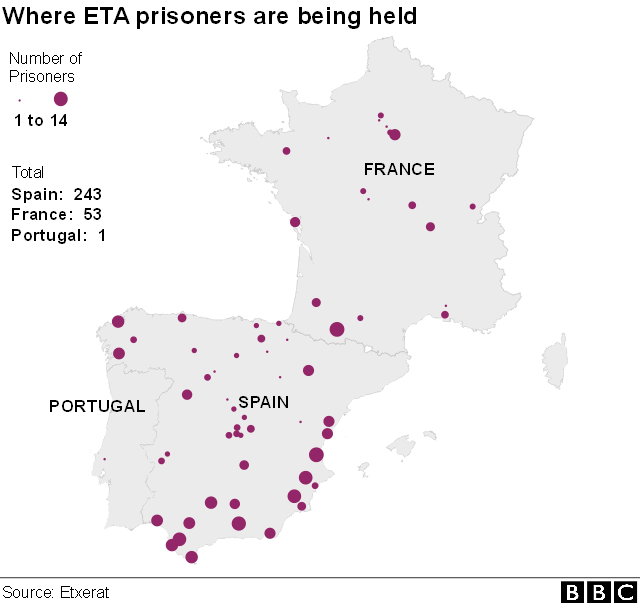

Meanwhile, the Spanish government intentionally keeps most of the 243 Eta members in national jails far from their families, as part of a so-called "dispersion policy".

"The biggest punishment of all for the prisoners is seeing that their relatives are also being punished by the penitentiary policy," said Olatz Iglesias, whose father, Juan Carlos Iglesias, is serving a 29-year sentence for murder in Alicante, 700km away from their home.

Only a small number of Eta members are estimated to be at large in Spain, while several dozen are believed to be living abroad, with Venezuela, Cuba and other Latin American countries their most favoured destinations.

Last month thousands of protesters took to the streets of Bilbao calling for prisoners to be moved to jails closer to the Basque region

So far, Eta's moves away from violence have failed to impress the Spanish government, which has presented the group's ceasefire, disarmament and now disbandment as a drawn-out admission of defeat.

With terrorism victims' groups, factions of the governing Popular Party (PP) and the conservative media all lobbying for a rigid line on Eta, there is little prospect of the government shifting its stance.

A recent partial apology issued by the organisation, in which it seemed to suggest that members of the security forces had been legitimate targets, did little to change that position.

"It doesn't matter if they apologise or not to us, because we will never forgive Eta," said Alfonso Alonso, leader of the PP in the Basque region.

After so many decades of bloodshed, Eta has little to show for its campaign.

The Basque region has more autonomy than any of Spain's other 16 regions, with its own police force, education system, language and a special financial relationship with Madrid.

However, these powers were granted to the region by the 1978 constitution, rather than as a result of Eta's actions.

In contrast with Catalonia, where support for secession is close to 50% and nationalist parties held a banned referendum last October, support for independence within the Basque country is currently around 15% according to polls.

In its letter Eta asserts that the Basque conflict with Spain and France is not over, but adds that it did not start with Eta either.

- Published8 April 2017