Macedonia and Greece: Deal after 27-year row over a name

- Published

Protests have been held in both Greece and Macedonia against a compromise on the name of the former Yugoslav republic

Greece has reached a deal on the name of its northern neighbour, which called itself Macedonia at the break-up of the former Yugoslavia.

After 27 years of talks - and many protests - they have settled on the formal name of Republic of North Macedonia.

Greece had objected to the name Macedonia, fearing territorial claims on its eponymous northern region.

It had vetoed the neighbour's bid to join Nato and the European Union.

The new name will now need to be approved by the Macedonian people and Greek parliament.

What's the solution?

Under the deal, the country known at the United Nations as Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (Fyrom) will be named Republic of North Macedonia.

Its language will be Macedonian and its people known as Macedonians (citizens of the Republic of North Macedonia).

Significantly, they agreed that the new name would be used both internationally and bilaterally, so that even the 140 or more countries that recognise the name Macedonia will also have to adopt North Macedonia. In Macedonian, the name is Severna Makedonija.

They also agreed that the English name could be used as well as the Slavic term.

Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev gave details of the deal in a live address from the capital Skopje

The two sides had earlier dropped a number of alternatives, including Gorna Makedonija (Upper Macedonia), Nova Makedonija (New Macedonia) and Ilinden Macedonia.

Why the problem?

The name Macedonia already belongs to a northern region of Greece that includes the country's second city Thessaloniki. By adopting the name in 1991, the new nation infuriated many Greeks, who suspected their northern neighbour of territorial ambitions.

The new state of Macedonia did not help matters when it named the main airport in its capital, Skopje, after Ancient Greek hero Alexander the Great, as well as a key motorway running from the Serbian to the Greek border.

During the 4th Century BC, the Macedonia of Alexander and his father Philip II before him ruled all of Greece and much beyond it.

Is this row really about Alexander the Great?

Only partly. Greece argues that Macedonia is an intrinsic part of Hellenic heritage, external. The ancient capital of Aigai is close to the modern Greek town of Vergina, while Alexander's birthplace is in Pella. As part of the deal, it is made clear that the people of North Macedonia have no relation to ancient Greek civilisation and their language is part of the Slavic family, unrelated to ancient Greek heritage.

But while Alexander remains a powerful symbol, recent territorial disputes over Macedonia are far more serious.

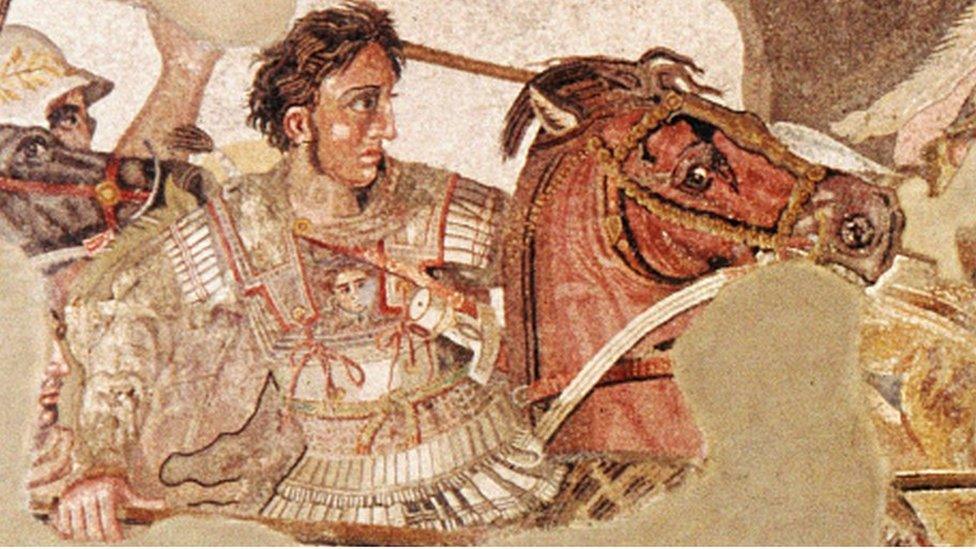

Alexander the Great ruled over Greece and created a vast empire in the ancient world

When the Ottomans were driven out of the broad region known as Macedonia during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, it was split up, mainly between Greece and Serbia, but a small part went to Bulgaria.

In World War Two, Greek and Yugoslav Macedonia were occupied by Bulgaria, an ally of Nazi Germany and Italy. Communists from both Yugoslavia and Bulgaria played a part in the Greek civil war that followed, so memories are still raw.

When Yugoslavia broke up, Greece would only accept the new country as "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (Fyrom)" at the UN, even though much of the world came to recognise it as Macedonia.

What has changed?

A new mood has emerged between the governments to put an end to the dispute.

Macedonia's government set the stage for a deal earlier this year when it renamed its airport "International airport Skopje" and the Alexander the Great motorway is now simply "Friendship" (Prijatelstvo in Macedonian).

There is also a push for a settlement both from the EU and Nato which some have put down to fears of creeping Russian influence in the Balkans. Greece is the main obstacle to Macedonia joining Nato.

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras and Macedonia's Zoran Zaev met on the sidelines of an EU summit in Bulgaria last month, prompting reports that a deal was close.

Then they had a long phone-call on Monday and followed it up with another conversation on Tuesday.

Mr Tsipras then gave details of the deal to the Greek president and then Mr Zaev went on live TV in Macedonia, hailing the agreement as historic and adding: "There is no way back."

Mr Tsipras gave a live address a little later, speaking of "a great diplomatic victory but also a great historic opportunity".

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg praised the two prime ministers for their "willingness" to solve the dispute.

The text is expected to be signed on Saturday on the shores of Lake Prespa, which spans the countries' borders.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Will the name fly?

The aim is to get Macedonia's parliament to back an agreement before EU leaders meet for a summit on 28 June. Greece will then send a letter to the EU withdrawing its objection to accession talks and a letter to Nato too.

That will be followed by a Macedonian referendum in September or October.

If Macedonian voters back the deal, their government will then have to change the constitution, a key Greek demand.

The deal will finally have to be ratified by the Greek parliament.

That may not be straightforward. Greeks are generally opposed to any name that includes Macedonia and some political parties are unlikely to back this.

On 13 June, the parties are expected to get a copy of the 20-page deal to examine before announcing their stance. Mr Tsipras insists that he has maintained all of Greece's "red lines" - but the document is likely to be leaked by those who oppose it.

Large protests against a deal were held in some 25 Greek cities earlier this month, from Pella to Thessaloniki. When big crowds descended on the centres of Athens and Thessaloniki in February, renowned Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis, 92, said the neighbouring northern state was illegitimate. "Macedonia was, is and will forever be Greek," he insisted.

What if it doesn't work out?

A lot can happen over a long, hot summer. Delays may hamper the planned timescale and there could be repercussions for both leaders.

Mr Tsipras and Mr Zaev will have to face down opposition within their own countries as well as beyond.

A nationalist party, Independent Greeks, may refuse to back the deal, but it is unlikely to put at risk a ruling coalition that it is part of.

Matthew Nimetz has spent more time on the name issue in two decades of shuttle diplomacy than anyone else

Although the two prime ministers have taken control of the issue, United Nations mediator Matthew Nimetz will likely be called upon to sort out any problems.

Since 1994, this US diplomat has quietly shuttled between Athens and Skopje searching for common ground that would eventually lead to a deal.

It is difficult to see how another deal could work.

- Published8 February 2018

- Published30 August 2014