Turkey election: Country's heart split over Erdogan victory

- Published

For conservative, pious Turks, Mr Erdogan is their voice

Ecstatic/distraught, relieved/incredulous: after yet another crushing Erdogan victory, Turkey's heart is again split in two.

How did it come to this?

His critics had hoped for so much. A fractured opposition had united for the parliamentary vote and looked set to deprive the president of his majority.

And in the presidential election, the centre-left CHP believed they had fielded a winner: Muharrem Ince was charismatic, he had the common touch, he drew vast crowds.

Polls suggested he would force Recep Tayyip Erdogan into a second-round run-off.

Turkey's economic boom has stalled, with inflation at 12% and the Turkish lira losing almost a fifth of its value this year, prompting anger among Mr Erdogan's support base.

Meral Aksener had looked set to eat into the president's votes

A fiery nationalist, Meral Aksener, looked set to eat into the president's votes. Mr Erdogan had stumbled in rallies. For the first time in 15 years, the opposition had dared to dream.

But Turkey's serial election winner proved his doubters wrong on both counts. At Mr Erdogan's party headquarters, there was an eruption of joy: the burst of fireworks mixed with the boom of his campaign songs; flags bearing his face were held aloft.

"He means everything to us - this country would cease to exist without him," one supporter told the BBC.

"Terrorist organisations lost, the Turkish nation won," said another, his two-year-old wearing an Erdogan head banner. "Real Muslims have won."

There were two surprises, which gave the president the victory he craved.

The first was that the combined score of Muharrem Ince and Meral Aksener was not higher.

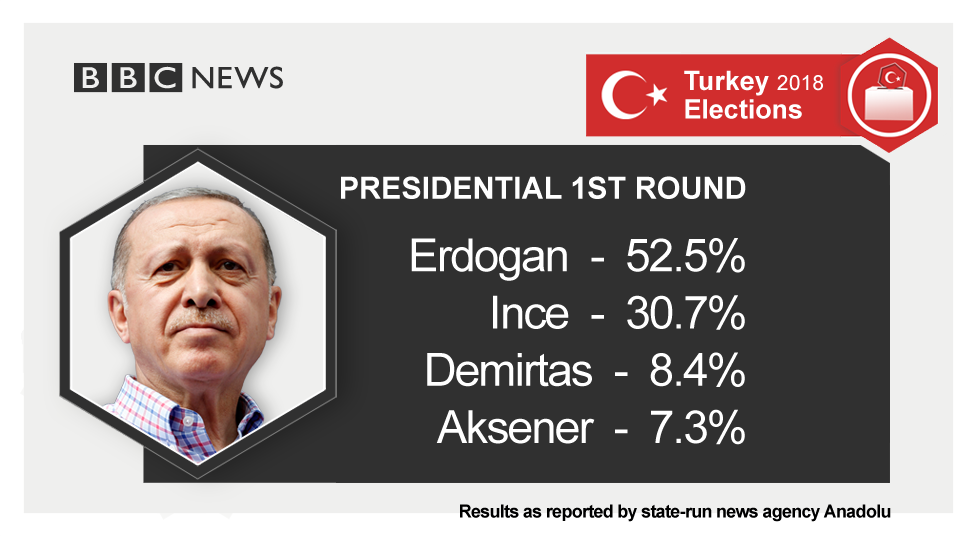

Mr Ince's 30.7% was a significant increase since he burst on to the campaign in April, although it was thought he could go even higher - his final rallies drew millions.

But Ms Aksener - nicknamed the "she-wolf" and once seen as the biggest threat to the president - polled lower than expected and than what was needed for a strong united front against Mr Erdogan.

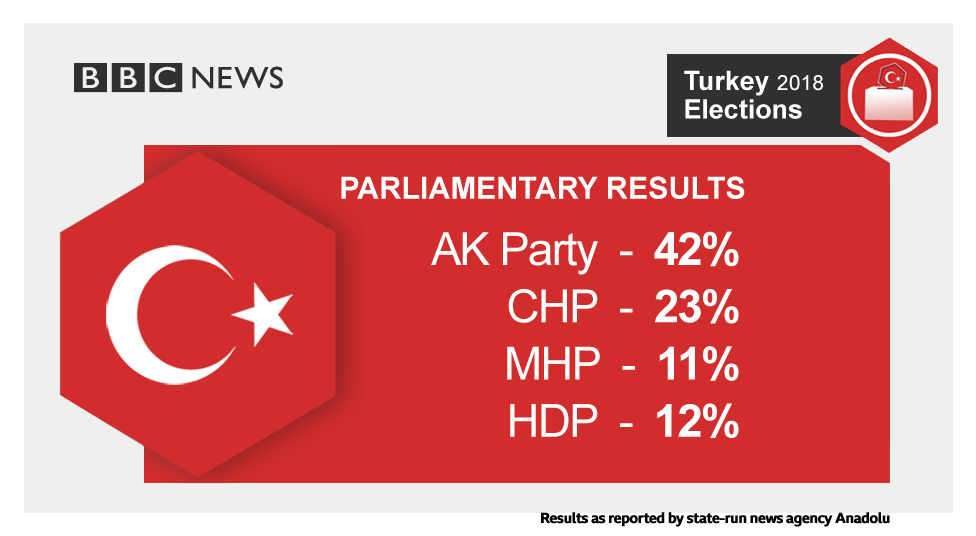

The second surprise was that in the parliamentary election, the president's far-right coalition partner, the MHP, far exceeded expectations.

Its leader, who is 70 years old, lacking any popular touch and who held virtually no rallies of his own, somehow managed to win his party enough seats to keep Mr Erdogan's parliamentary majority intact.

The claims of manipulation are loud.

During the count, the opposition alleged that the state news agency, Anadolu, was calling results long before ballot boxes were opened.

Millions of votes had not been counted, the CHP said, and yet the only source of figures was a news agency under the president's thumb.

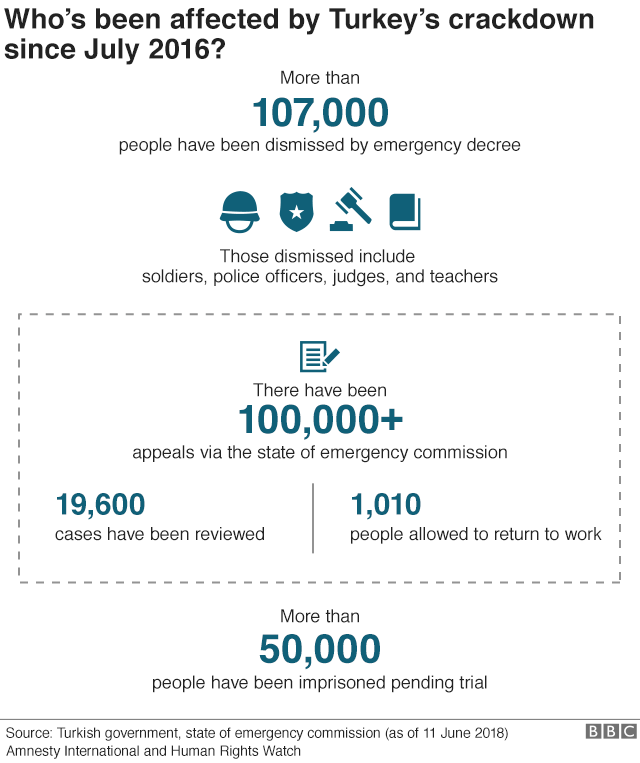

Other media which used to tally elections were closed down or sold off during the crackdown of the past two years.

The government, and Anadolu, deny any falsehood. Mr Erdogan warned his opponents not to discredit the figures "to cover up its failures".

The fact is that the Erdogan side of this country will simply not countenance defeat. For conservative, pious Turks, he is their voice - their very survival - in a country where many felt marginalised under past secular governments.

For them, a shutdown of Twitter here, a jailing of journalists there is of no concern. It is the gleaming bridges, airports, schools and hospitals built under Mr Erdogan which have transformed their lives and which earn their unwavering loyalty.

To his critics, his shouting matches with Western leaders are repugnant and take Turkey further than ever from its long-held dream of EU membership. To his supporters, the defender of their nation is standing up to imperialists who failed to destroy Turkey after World War One, but are still trying.

The consolation for the president's opponents is that the pro-Kurdish HDP party - hit by mass arrests and persecution, its leader having run for the presidency from prison - managed to cross the 10% threshold to enter parliament and win more than 60 seats. It will keep its strong voice of equality and democracy.

And the other consolation was that despite 90% of the media being pro-government and largely shunning the opposition, the president's posters and flags dwarfing any others on the streets, the election being held under a state of emergency, the curtailment of protests, and critical journalists and academics being jailed or forced into exile, Mr Erdogan only got half of the country behind him.

"We are living through a fascist regime," the opposition MP Selin Sayek Boke told the BBC.

"But fascist regimes don't usually win elections with 53%, they win with 90%. So this shows that progressive values are still here and can rise up."

For now, though, this is Mr Erdogan's time.

With his sweeping new powers, the scrapping of the post of prime minister and the fact that he will be able to choose ministers and the most senior judges, he becomes Turkey's most powerful leader since its founding father Ataturk.

He will now hope to lead the country at least until 2023, 100 years after Ataturk's creation. And a dejected opposition will have to pick itself up and wonder again if, and how, he can be beaten.

- Published25 June 2018

- Published25 June 2018

- Published18 June 2018

- Published15 June 2018

- Published21 June 2018

- Published8 June 2018

- Published22 June 2018