Notre-Dame fire: Why the cathedral's beauty wins hearts around the world

- Published

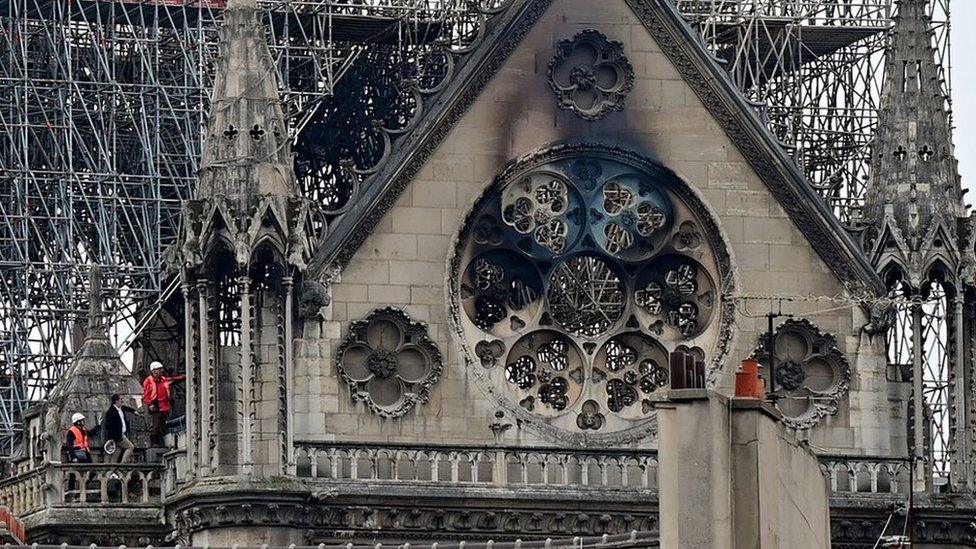

Notre-Dame, burning orange against the Parisian sky, was a sight both horrifying and spectacular; unbearable and mesmerising.

The audible gasp as if from one single mighty breath when the lead spire slipped from sight reflected the global response to the catastrophe. It was seen on screens from China to the US.

Built from the late 12th Century, Notre-Dame was a trailblazer in the development of the Gothic style and is one of its most recognisable examples.

The uplifting brightness of the interior demonstrates the masons' aspiration to manipulate light and space as well as stone and mortar.

Outside the west facade is a vast billboard of sculpted figures composed to harmonise with the architectural structure and to convey the historic might of the medieval church.

Notre-Dame is more though than a paean to the Middle Ages. Its foundations rest on the most ancient inhabited site in Paris, the Celtic town of Lutetia, dating back to at least the first century BCE.

Notre-Dame "gargoyles" look out over the city

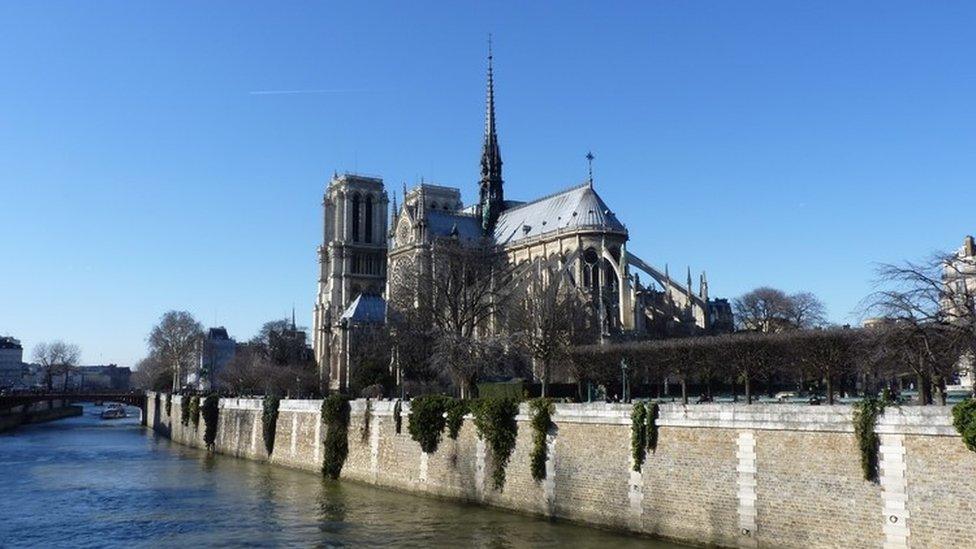

Its location on an island between two branches of the Seine sets it apart from the city, although in its midst. It breaks the flow of the river and in doing so subdues it.

Notre-Dame was built from the 1160s at the instigation of Bishop Maurice de Sully to replace a vast Seventh Century cathedral on more or less the same site.

With its innovative floor-plan and complex multi-storied west front, it lies at the forefront of the French Gothic movement. St Denis though, in Paris's northern suburbs, was feeling its ways in that direction some 30 years before.

However, the significance of Notre-Dame in terms of public affection surely lies in the role it plays in the emergence of France.

If its kings were crowned at Reims and buried in St Denis, geographically and historically Notre-Dame stands at its heart.

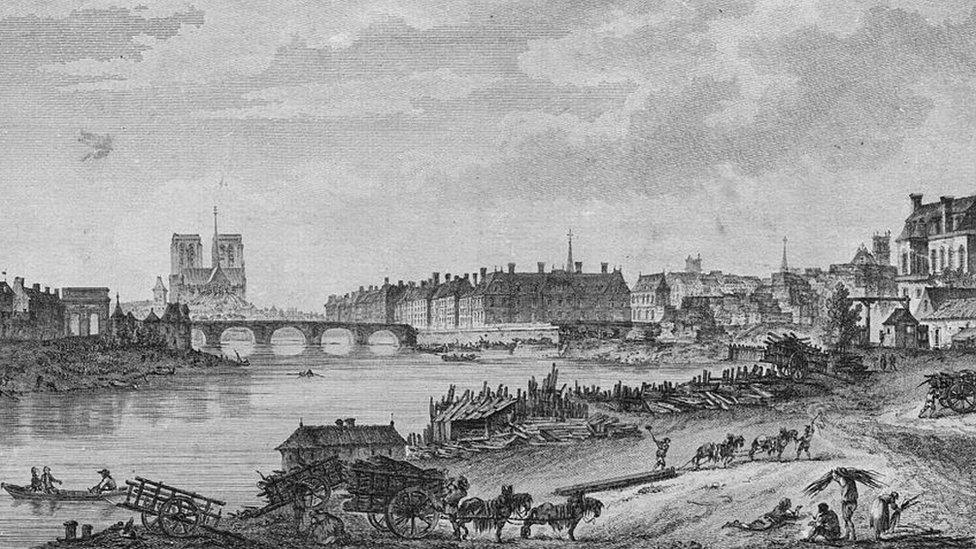

Engraving showing Notre-Dame shortly before the French Revolution

The building grew with the nation.

The decades which marked its construction saw Normandy and the South-West absorbed into its political orbit. Its university led intellectual thought in Europe and King Louis IX was recognised and subsequently canonised for his piety.

Later, in the 1790s, Notre-Dame was again at the centre of change across France.

In the same way when France was wracked by revolutionary unrest, the cathedral was ransacked and disfigured by zealots.

The physical scars left on Notre-Dame were, almost symbolically, both grave and permanent.

Sculptural fragments from the west facade were rescued from the site and are now in the city's Musée de Cluny. They serve as a ghostly reminder of what Notre-Dame had been, how it had come to represent privilege and the status quo, and why it was reviled by the Paris mob.

When stability of a kind returned, it was reincarnated in the Neo-Gothic restoration work of the remarkable Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, saviour almost singlehandedly of France's Medieval architectural legacy.

The famous grotesque "gargoyles" that he added to the parapets leer over to the opposite river banks and the new Classically-inspired city layout being created by Baron Haussmann at much the same time.

Notre-Dame is not only a mirror of the nation's history but a waymarker in the modern life of the city.

It is not simply a thoroughfare across the river but a destination in its own right.

The 19th Century system of arrondissements radiates from Notre-Dame; the map of the Metro constellates around the Île de la Cité on which it stands; river boats run up on either side, as does traffic by the Seine.

Small wonder then that Notre-Dame has an indelible place in the hearts of Parisians, and also in those of her endless stream of visitors.

Small wonder too that the burning fireball seemed to so many like a heart wrenched from a body.

The image is apt because, in many ways, a great building is like a living thing.

Parts of it fall away and are replaced, parts are added and others demolished, parts are joined together and others divided up.

Notre-Dame as a Paris landmark

One of France's most famous landmarks since it was built 850 years ago

A stone outside marks "Point Zero" - the official centre of the capital and the marker in France from which all distances to Paris are measured

A major symbol of the Catholic faith, the cathedral is home to relics including the crown of thorns said to have been worn by Jesus before the crucifixion

Attracts an estimated 13 million visitors a year

Snapshots taken of such a building, say, every 50 years, would demonstrate visible changes.

Someone looking at Canterbury Cathedral in 1100, for example, would see nothing at all in the fabric which remains in the building above ground level now.

A building therefore is an elusive concept, and our response to it is as much to do with how we think of it in our hopes and our memories as it to do with its physical appearance.

In past centuries these gradual changes were frequently punctuated by catastrophe.

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo and wife of the French president, Brigitte Macron, attend a service

Medieval accounts abound with collapses, earthquakes, and especially fire.

In England, the cathedrals at Winchester, Ely and Wells lost their crossing towers; Lincoln was destroyed by an earthquake, leaving just its west facade standing.

In France, 12th Century Chartres burnt to the ground, and Beauvais' crossing tower, the highest ever built, fell down within a decade of its construction.

Most were rebuilt afresh in the latest fashion.

From a great fire, the Gothic cathedral of Chartres with its unprecedented programme of stained glass arose. And from a pile of rubble, the ingenious wooden lantern which is the Ely octagon was constructed.

Yet Chartres is still Chartres and Ely is still Ely.

Even buildings left as bereft fragments have not lost their identity. Nor is Notre-Dame lost until those who love it have gone.

What will happen now? Will that Neo-Gothic lead spire be replaced by a Neo-Neo Gothic one?

Or will Paris take a tip from the Middle Ages and rebuild what is ruined in a new way?

And there is good news - the rose windows and the organ are saved, many works of art were carried unharmed from the flames; the courage and efficiency of the firefighters is uplifting; the determination to rebuild heart-warming.

The signs are that Notre-Dame, like so many great churches in the past, will rise phoenix-like from the ashes.

If imagination and boldness are given rein, it may shine even more brightly than before.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Catherine Oakes, external is an expert in medieval art and architecture and is director of studies for History of Art at the University of Oxford's Department for Continuing Education.

- Published17 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published15 April 2019

- Published15 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published5 March 2018