How Greek crisis helped removed taboo on mental health

- Published

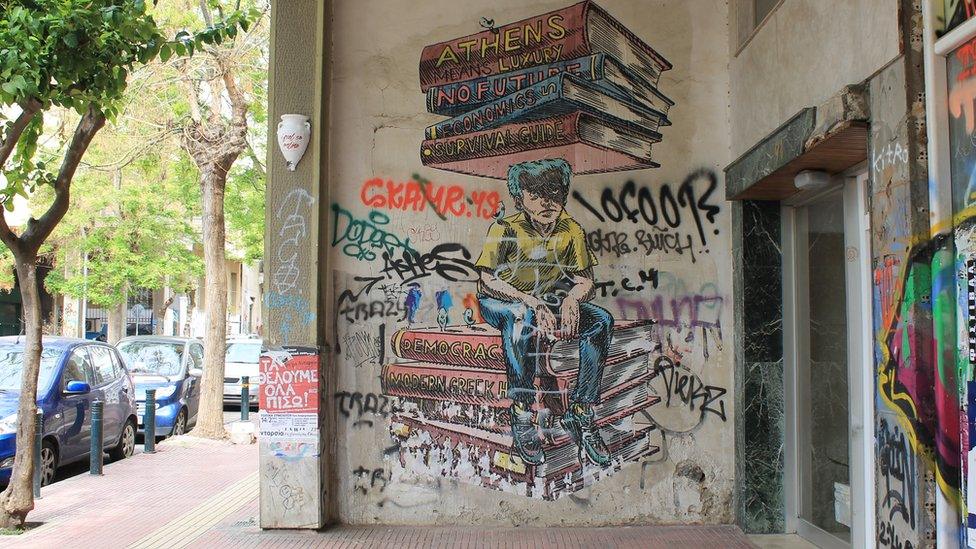

Mental health funding in Greece has declined as it has gone through years of austerity (file pic)

When Areti Stabelou graduated from university in 2012, Greece was at the height of its economic crisis. Unemployment had more than doubled, and the struggle to find work left her feeling depressed.

"It was very difficult to talk about in those early years," she said. "The crisis was affecting everyone's mood, but we all assumed we were the only ones feeling that way."

But as the years passed, Areti noticed her friends' and families' attitudes change. "The more of a toll [the crisis] took on everyone's lives, the more openly we began talking about it," she said.

Mental health has long been a taboo subject in Greece, but the country's decade-long financial crisis has given the issue greater visibility.

I think we Greeks have removed the guilt from depression

What went wrong

Poverty soared as the Greek economy contracted by a quarter and unemployment hit 27%. As the true state of Greece's economy became clear, it was given three bailout packages from the EU and IMF to keep afloat.

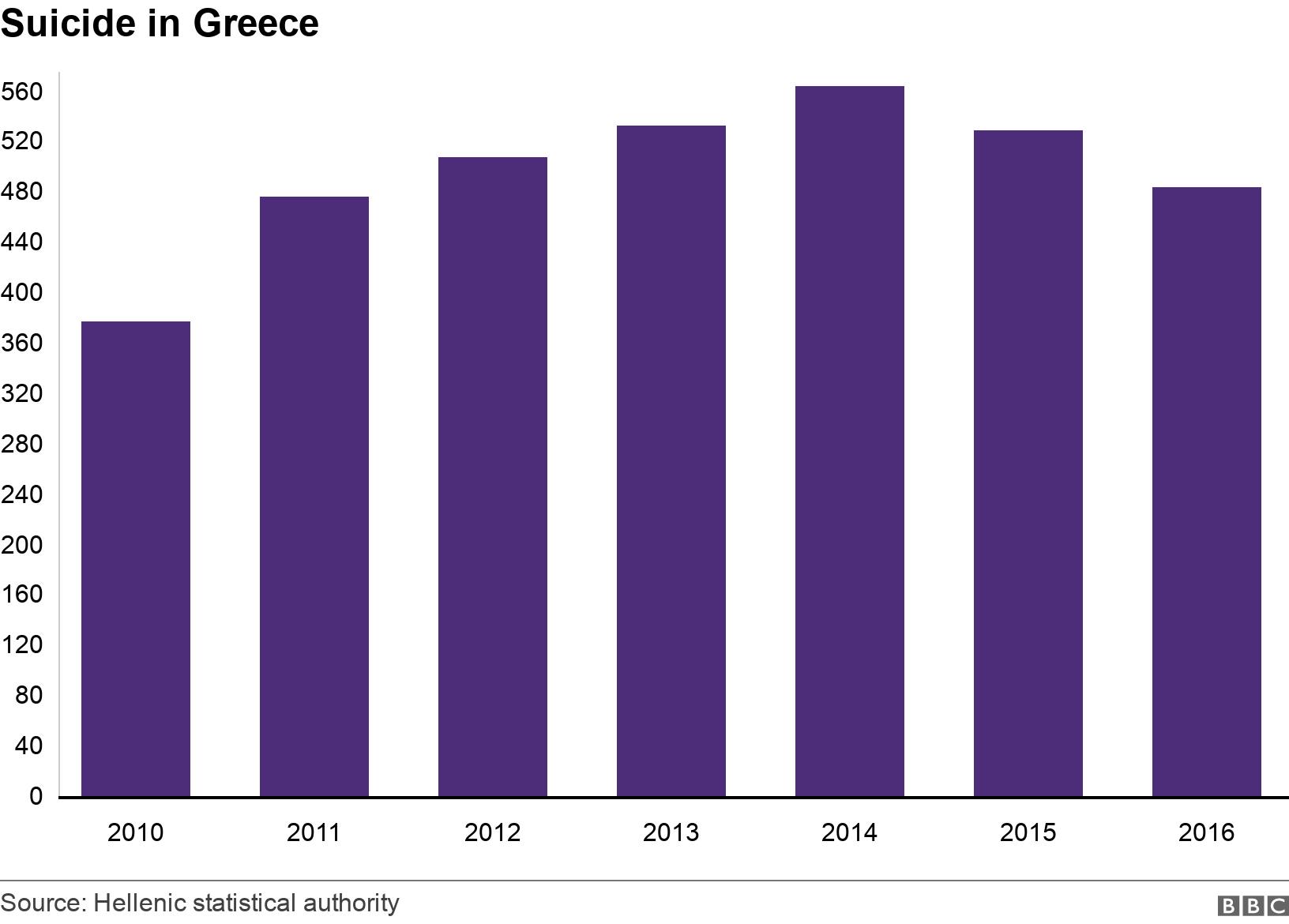

The percentage of the population suffering from depression for one month or longer rose from 3.3% in 2008 to 12.3% in 2013 and suicide rates jumped by 40%.

Graffiti in Athens shows a man weighed down by the pressures of modern life

At the same time, funding for mental health services was cut by more than half.

"Until a few years ago, society did not give this issue any attention," said Dr Kyriakos Katsadoros, the founder of Klimaka, Greece's only suicide prevention clinic. "The crisis has brought problems that were being ignored to the forefront."

Conservative attitudes are changing as a result. In 2009, 63.1% of Greeks agreed with the statement that depression is a sign of personal weakness. By 2014, that number had dropped to 36%.

At Aiginiteio psychiatric hospital, patients of all ages and backgrounds flow through the doors, and temporary, modular surgeries have been erected outside to deal with increased demand.

"Media coverage has helped underscore the link between depression and the recession," said hospital director Prof Papageorgiou Charalambos.

Through their own experiences, Greeks came to empathise more with those affected, a nurse at the hospital told the BBC. "Once the crisis hit, people could not afford private therapists and they had to come here," she said. "They could see for themselves that mental illness can affect anyone."

Talking openly about depression

Among the biggest challenges has been changing the stance of the Greek Orthodox Church, said Dr Katsadoros from the Klimaka clinic. The Church considers taking one's own life a sin.

"Priests would not say burial prayers for people who had taken their lives," he said. "Doctors would often record a different cause of death in order to protect the family from shame."

As a result, Greece's low suicide rates have always been accompanied by a large number of "accidental" poisonings and falls.

"Now, younger priests believe the Church has an important role to play in preventing suicide," Dr Katsadoros said.

Burial prayers are now allowed if a doctor confirms the deceased was suffering from mental illness. "Today, if we have a patient with suicidal thoughts, our professionals can talk to their families and ask how they are<" Dr Katsadoros said. "This was impossible before."

The suicide prevention clinic has its own online radio station, run by 69-year-old Katerina Morfoniou, who got involved when her husband took his life six years ago.

"After it happened, I made a decision to close my eyes and ears to the shame. It's just the way my personality is," she said. "I hope when people hear me talk on the radio about it, it will make them more comfortable about speaking openly, too."

On air and online, Katerina Morfoniou believes her shows can play an important role

Ms Morfoniou invites doctors on the radio and encourages other patients at the centre to start their own shows. She believes things are changing in Greece. But Areti Stabelou sees a big difference in generations.

"Some older people still do not believe that mental illness is a legitimate illness," she said. "Younger people, having lived through all these years of crisis, realise that depression is the prevalent health issue of our times."

Greeks may be talking more openly about mental illness, but there are still huge barriers facing those who need support. "I could never afford to see a psychologist so I just dealt with my depression alone," admitted Ms Stabelou.

That is because the health service is struggling with what hospital director Professor Charalambos sums up as a shortage of staff, cuts in their salaries, reduced medical supplies and inadequate primary care.

The next challenge is to get the state to implement a Greece-wide prevention policy, said Dr Katsadoros. "We believe 90% of suicides could be prevented if friends, family and professionals recognise those at risk," he said.

"Behind every death, there is always a lack of knowledge."

Are you affected by this?

In Greece, Klimaka runs a phone helpline in English and Greek on 1018.

For information and support on mental health issues in the UK, the BBC has a list of relevant organisations.

The Samaritans helpline is available 24 hours a day for anyone in the UK struggling to cope. It provides a safe place to talk where calls are completely confidential.

Phone for free: 116 123 or email: jo@samaritans.org

- Published6 September 2015