End of Greek bailouts offers little hope to young

- Published

More than eight years of brutal cuts led to anger at both Greek leaders and European lenders

On Monday, Greece ends its third and final financial bailout programme, having received €289bn (£259bn; $330bn) over eight years.

The government and its European lenders are keen to paint the end of the last bailout as a good thing, having avoided a "Grexit" in which the country would have crashed out of the eurozone into unknown territory.

But for many Greeks - especially the young - the damage has already been done.

A recent poll indicates that three-quarters of the population think the country is headed down the wrong path. The same number think the bailout deals, rather than saving Greece, actually harmed the country.

Taxes remain high and more than 90% of Greeks believe the lenders will keep a close watch on the country's spending for years.

Here's how the crisis played out.

Young hit hard

The crisis hit all parts of Greek society - but it was particularly hard on the young.

Between 2008 and 2016 the country lost almost 4% of its citizens to emigration - more than 400,000 people. And while Greece didn't record the ages of those emigrating, the country is getting older.

The average (median) age has jumped by more than four years since 2008; and while those aged 20 to 39 used to make up 29% of the population, that's fallen to just 24%.

Giorgios Christides is a Greek journalist covering his country for German news magazine Der Spiegel. Back in 2012 he wrote a piece for the BBC about his friends "fleeing Greece one by one".

He says the economic improvements since the peak of the crisis in 2012 are not enough to have changed that.

Greeks love their country, and many "would return the second they thought they could find a worthwhile job and good prospects back home", he says.

Low wages and high taxes for the self-employed make those good prospects rare. Even a "best-case scenario" of a permanent job presents difficulties "if you want to leave your parents' home, have children, lead a full and meaningful life," he said.

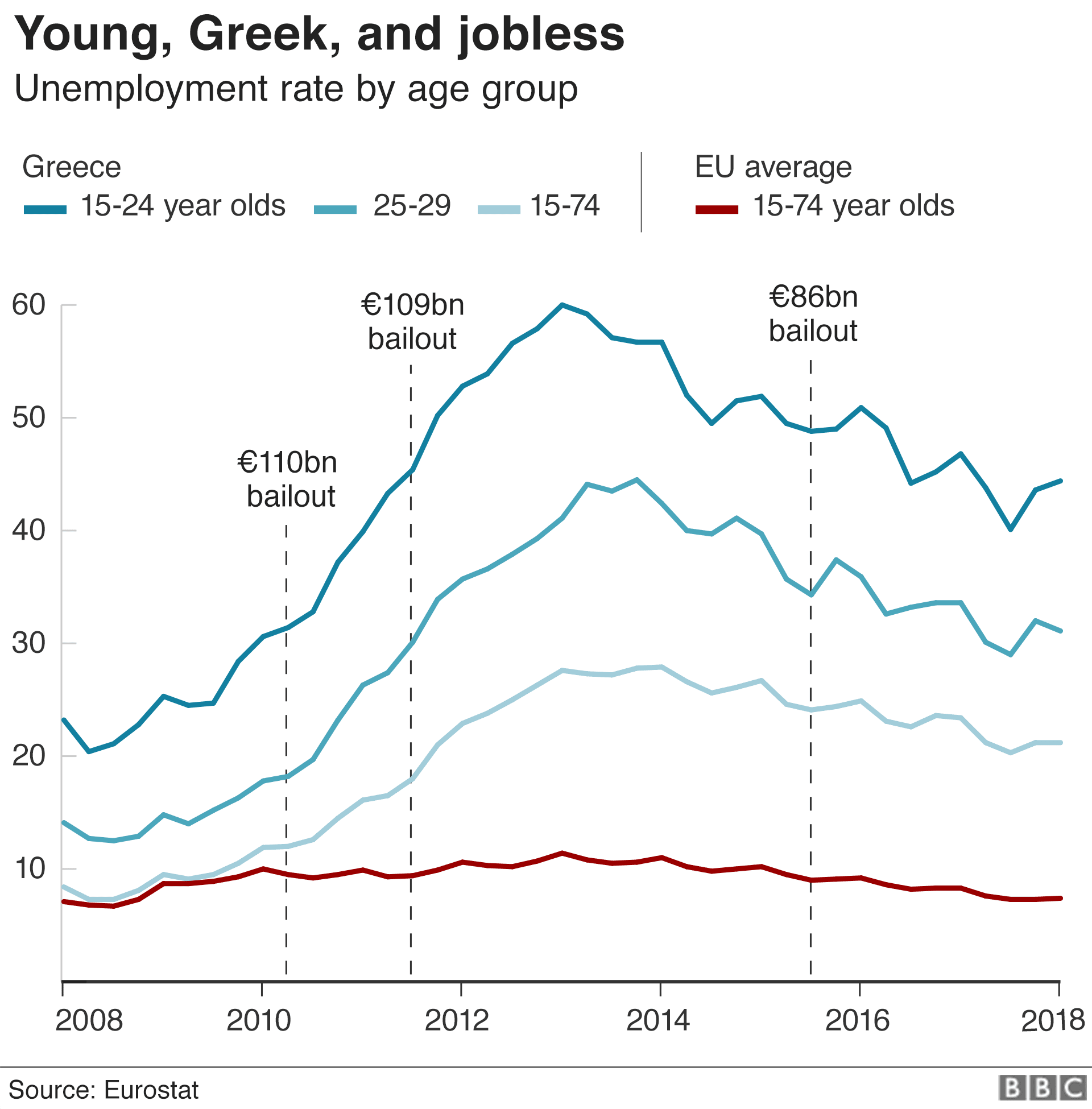

Part of the reason for the exodus is a lack of job opportunities. Greece's unemployment rate peaked at 27.5% in 2013 - but for those under 25, it was more than double that, at 58%.

Last year, more than four in every 10 young Greeks were still jobless.

"People are persuaded, and rightly so, that austerity policies will continue for the years to come," says Dr Vasilis Leontitsis, a lecturer in Globalisation Studies at the University of Brighton.

Back in 2011, Mr Leontitsis wrote a blog post about a "lost generation", and a young Greek woman he met in Athens, external. She was one of the lucky few with job in a café.

"I know that I am going to have a difficult future," she told him. "My friends and I have stopped planning... because no matter how much we plan, nothing is to materialise."

Mr Leontitsis says he's followed her progress since.

She was excited to get a promising job in online sales, but the company's poor performance meant she lost that within six months. Since then, she has only secured a part-time job in a packaging firm - relying on her family to make ends meet.

"When I wrote about Greece's lost generation, I meant exactly this," Mr Leontitsis says.

"[Young people] are disillusioned regarding job prospects in Greece. Scores of young people - among them many educated - have left the country aiming for a better future in other EU countries and beyond."

Today, he says, "the everyday reality of the country's youth remains extremely precarious".

How did Greece get here?

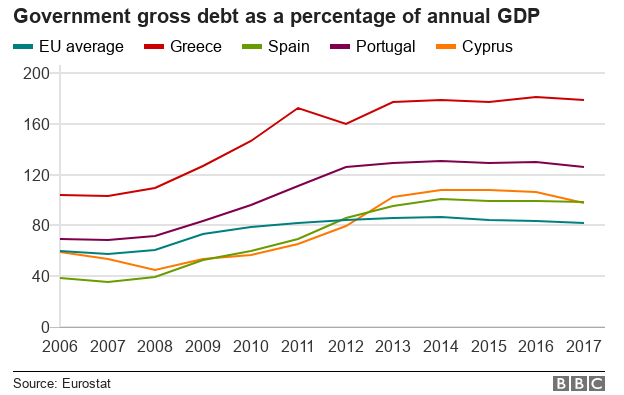

The global financial crisis began to really hit the eurozone after 2008. Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus each needed bailout loans to stay afloat. But things were worse in Greece.

In late 2009, it emerged that Greece's national budget deficit - or annual debt - was more than 10% of the country's entire economy (GDP).

By the end of the year, credit rating agencies had downgraded Greece's status, making it harder for Greece to borrow.

But the true scale of the Greek problem was worse than it first appeared.

The European statistics agency had raised concerns about Greece's economic estimates, external years earlier. Then, in 2010, it emerged that the financial data had been misreported. Past numbers had to be revised upwards and confidence in Greek data was shattered.

Tax evasion was rampant and Greece was rated the most corrupt country in the EU in 2012.

Something had to be done.

In the first part of 2010, the government brought in sweeping austerity packages, cutting public pay and raising taxes. But it still wasn't enough.

In 2010, the first wave of austerity measures prompted protests and violent clashes in Athens

By May, a nearly bankrupt Greek nation struck a deal with the so-called "Troika" - the EU, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund - none of which wanted to see Greece default on its debt, fearing a knock-on effect on other nations.

This was the first bailout - a loan of €110bn. But it came with a condition: even more budget cuts.

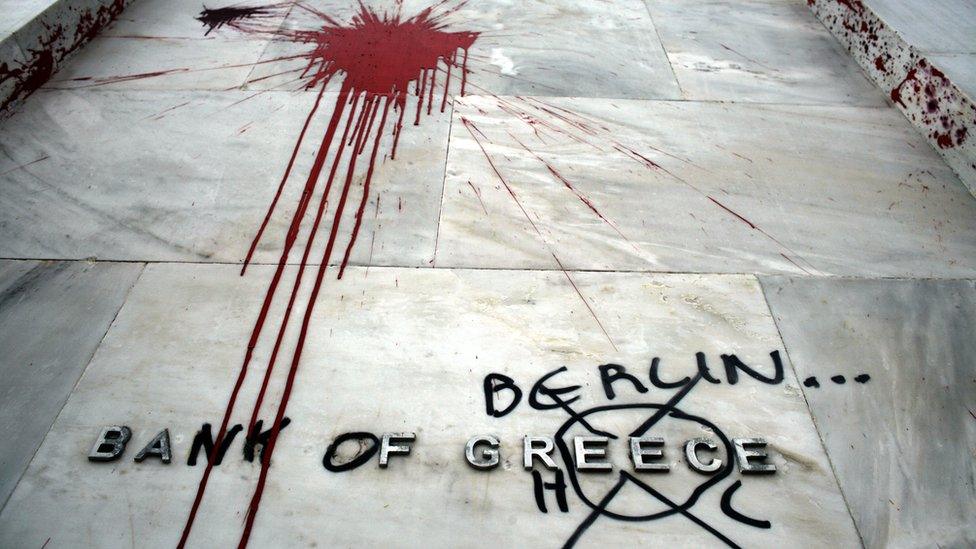

Violent protest

Street protests broke out against the strict austerity measures, eventually turning violent, and even resulting in a handful of deaths.

In Athens, February 2012 - fire bombs are thrown in the streets

The unrest continued, while Greece's credit rating was downgraded to "junk" status. More austerity followed the next year, and unemployment began to rocket.

In 2011, the second bailout was agreed, this time for €109bn, later revised upwards to €130bn.

Protests continued, and in politics, anti-austerity parties promising to reject spending cuts began making gains. Youth unemployment peaked in 2013 at almost 60%.

Anti-EU sentiment was displayed at many protests - from the burning of the EU flag to signs about Greece being a "colony" of German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

In December 2014, the beleaguered Greek government finally collapsed.

2012: Supporters of the soon-to-be PM Samaras rally in Athens - he lasted less than three years

In its place, the anti-austerity, left-wing Syriza party won its first national victory.

"Syriza soon realised it had to adopt austerity policies as prescribed by the Troika," Mr Leontitsis says. "The political and economic revolution it had envisioned on paper never materialised."

"Not only did Syriza alongside its coalition partner maintain austerity policies, but in many cases it strengthened them."

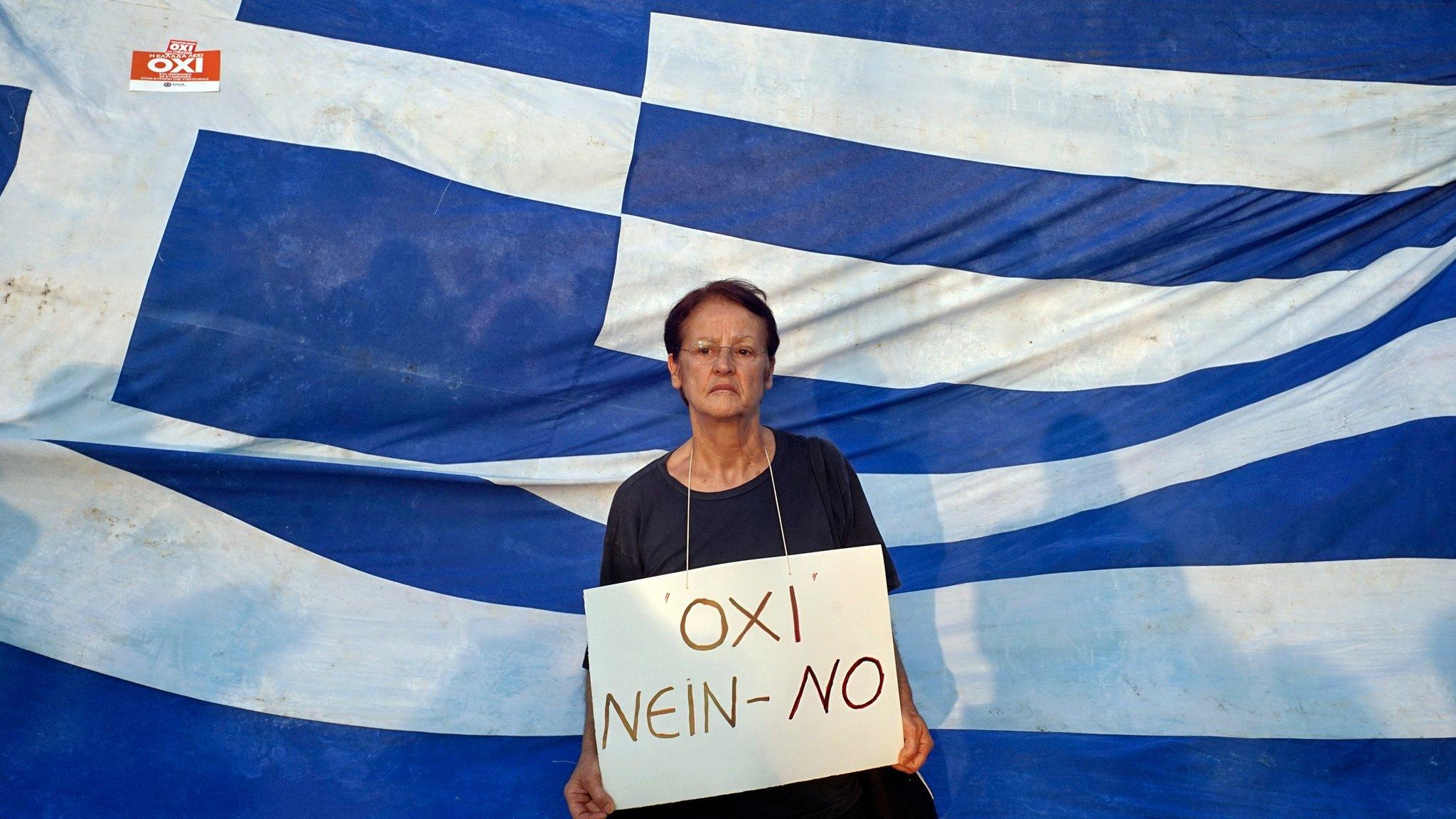

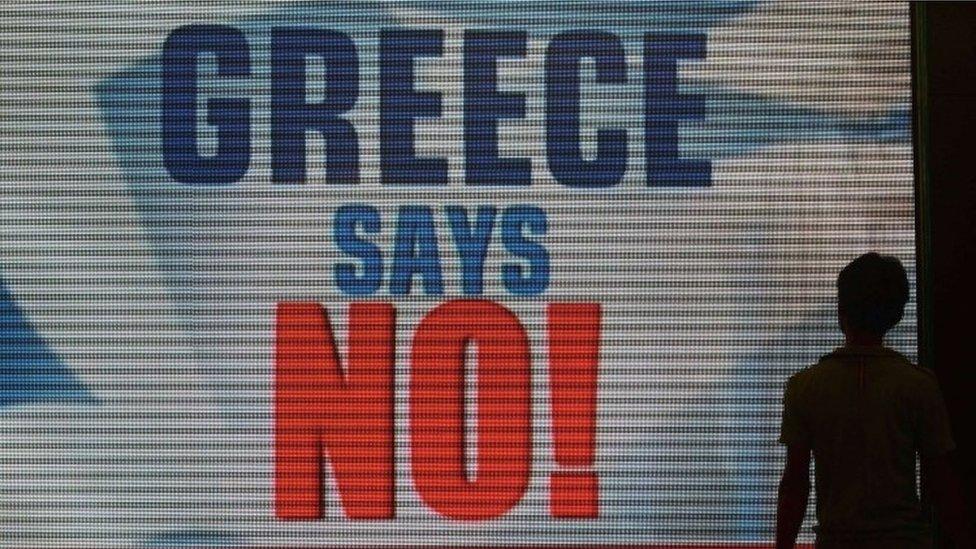

Greece ended up needing a third bailout - even though, in a referendum organised by Syriza, a majority of Greeks rejected it.

2015 was a tumultuous summer: banks closed, cash withdrawals were limited, and the Greek stock exchange closed for the month of July.

The summer of 2015 - before the third bailout - saw its own share of unrest

The government eventually agreed the third bailout of €86bn in August.

Now, three years later, that third and final programme of loans to Greece is ending. But the effects could be felt for decades.

Hopes for the future

Giorgios Christides' priorities have changed since 2012, when he told the BBC his friends were leaving. Now he's worried for his children, aged five and 11.

"I am wary about their future here," he says. "Experts warn it will take years or decades for Greece just to return to the pre-crisis prosperity levels.

"Which is why parents like me try, to the best of our abilities, to provide our children with the skills and knowledge that can help them get an education and land a job abroad - if need be."

But the Greek people have huge potential, he says.

"I am not giving up... I believe it is our duty to at least try to make it here, before calling it quits and moving abroad."

- Published16 July 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published25 May 2016

- Published15 June 2017

- Published21 August 2015

- Published28 November 2022

- Published10 January 2018

- Published10 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015