Swiss Crypto AG spying scandal shakes reputation for neutrality

- Published

Has the Crypto AG scandal shattered Swiss neutrality?

It's hard to exaggerate just how much the Crypto AG scandal has shaken Switzerland.

For decades, US and German intelligence used this Swiss company's encoding devices to spy on other countries, and the revelations this week have provoked outrage.

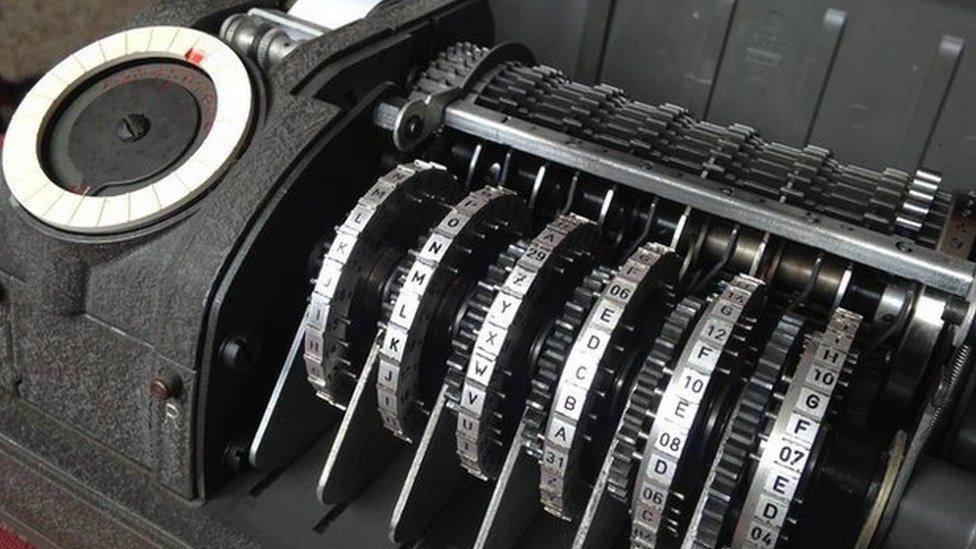

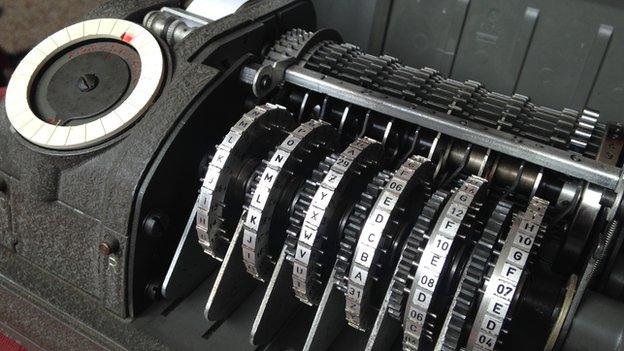

From the Cold War into the 2000s, Crypto AG sold the devices to more than 120 governments worldwide. The machines were encrypted but it emerged this week that the CIA and Germany's BND had rigged the devices so they could crack the codes and intercept thousands of messages.

Rumours had circulated in the past but now everybody knows.

Why Swiss neutrality matters

There are only a handful of countries on the planet that have chosen neutrality; Austria is one, Sweden another. But no country has made a status symbol out of neutrality like the Swiss.

Now that the Crypto AG scandal has emerged in all its tawdry detail, there's not a newspaper or broadcaster in the country that is not questioning Switzerland's neutrality.

"It's shattered," is a common phrase.

A federal judge is already on the case and politicians across the spectrum are calling for a parliamentary commission of inquiry.

This is a country whose neutrality has allowed it to represent US interests in Iran for 30 years, and Tehran's interests in Washington. Switzerland negotiated hard behind the scenes with the US to allow deliveries of humanitarian aid to Iran to ease the worst effects of sanctions.

It is also a country that sold flawed encryption machines, bearing that Made in Switzerland label, to Iran, so that Washington could eavesdrop.

Swiss company Crypto made CX-52 encryption machines

Swiss neutrality is revered as if it were in the country's DNA, part of a unique national identity, and not the pragmatic policy of a small country that hired mercenaries to the rest of Europe until its leaders decided not fighting at all might be safer.

"We survived two world wars," is a phrase you often hear in Switzerland. It can be irritating to citizens of other European countries who also survived those wars, in rather more harrowing fashion.

But it's true, Switzerland's neutrality kept it out of those wars, and in 1945 Switzerland's economy and infrastructure emerged, phoenix-like and unscathed, while its neighbours swept up the ash and the rubble.

How the Swiss made themselves useful

Neutrality, however, is not some force field which keeps enemies out. Not a magic word which you can chant and the bad guys will leave you alone.

In World War Two, Switzerland did all sorts of things to make sure its neighbours stayed away.

Mass mobilisation, sending every man between 18 and 60 to defend the borders, mining the tunnels and alpine passes, that was one thing: and until recently that took pride of place in Swiss history books.

But there was something else, equally important: Switzerland made itself useful, to all sides.

Switzerland's forces barricaded its borders in World War Two

Nazi Germany found a safe place for its looted art and gold in Swiss banks. It sent trains full of weapons across Switzerland to support Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

At the same time, Switzerland's head of the armed forces, General Henri Guisan, was having secret chats with the French about fighting together should both countries be invaded. There's a street named after Guisan in every Swiss town.

Meanwhile the US intelligence-gathering body, the Office of Strategic Services, sent Allen Dulles to Europe.

Dulles set up his office in the Swiss capital, Bern, and stayed there for the rest of war, spying on the Germans. He later became head of the CIA.

Who knew what?

In the 1990s the Swiss did a lot of soul searching about World War Two.

The history books were rewritten to include the shameful policy of turning Jewish refugees back at the borders. Commissions of inquiry were set up, memorials held, and a Swiss government minister, Kaspar Villiger, formally apologised.

That's the same Kaspar Villiger who now stands accused, while serving as defence minister in the 1990s, of knowing that the CIA controlled Crypto AG, and was selling flawed encryption machines around the world in order to spy on foreign governments.

Mr Villiger, it must be stressed, denies this. But many questions about Crypto were raised in Switzerland in the 1990s, so it's curious that the defence minister didn't hear them, or didn't follow them up.

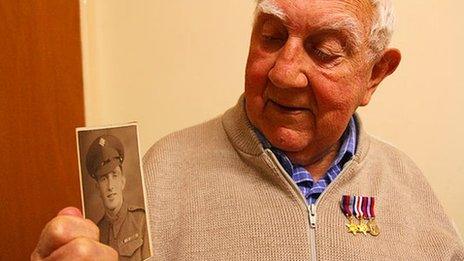

Kaspar Villiger served as defence minister in the 1990s

Asked about Mr Villiger on Swiss TV, rotating federal president Simonetta Sommaruga, said the speculation made no sense. "We will discuss it when we have the facts," she said.

Can Switzerland have it both ways?

How on earth can those two concepts - neutrality and cooperation - exist together?

Perhaps in the same way that Switzerland proudly does not fight wars, but sells plenty of weapons.

Or the way in which its bankers used to say "money doesn't smell". In other words, they were happy to look after it whatever bloody conflict, brutal dictator, drug baron, or tax scam it had come from.

Or, more charitably, Switzerland wanted to survive the Cold War. Its values were Western, why not turn a blind eye to a few covert operations by Europe's protector in chief, the US, at one of Switzerland's world-class precision engineering companies?

To be fair, there are millions of Swiss who think deeply about these things, and who have campaigned hard for a less self-interested policy, certainly when it comes to banking and arms trading, both of which are now subject to much stricter regulation.

But still, every few years it seems the Swiss get a wake-up call about their neutrality.

They have to learn all over again that it's not a shining beacon of hope at the heart of Europe. Rather it is a pragmatic and often grubby survival tactic in a continent with a very bloody history.

And sometimes, as with Crypto AG, that pragmatism, together with a desire to see the myth of neutrality rather than the reality, leads to some very questionable decisions.

More stories from the BBC on spying

What it takes to be a spy in the digital age

- Published25 November 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published30 May 2016

- Published28 July 2015

- Published11 February 2013

- Published28 December 2011