Ukraine war: Where are Russia's opposition leaders now?

- Published

Russian critics and opponents of President Putin are often punished - or worse

President Vladimir Putin now rules Russia virtually unchallenged. Many of the critical voices that once spoke out have since been forced into exile, while other opponents have been jailed - or in some cases killed.

By the time he launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, more than two decades of stamping out dissent had all but annihilated opposition in Russia.

At the very start of President Putin's rule, he brought to heel Russia's powerful oligarchs - immensely rich people with political ambitions.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, once head of the Russian oil giant Yukos, was arrested in 2003 and spent 10 years in prison for tax evasion and theft after funding opposition parties. Upon his release, he left Russia.

Boris Berezovsky, another oligarch who even helped bring Putin to power - fell out with him later and died in exile in the UK in 2013, reportedly by suicide.

All key media in Russia gradually fell under the control of the state or toed the official Kremlin line.

Alexei Navalny

By far the most prominent opposition figure in Russia is now Alexei Navalny, who has accused Putin from jail of aiming to smear hundreds of thousands of people in his "criminal, aggressive" war.

In August 2020, Navalny was poisoned with Novichok, a military-grade nerve agent, while on a trip to Siberia. The attack nearly killed him, and he had to be flown to Germany for treatment.

In May 2022, Alexei Navalny unsuccessfully appealed against a nine-year prison sentence

His return to Russia in January 2021 briefly galvanised opposition protesters, but he was immediately arrested for fraud and contempt of court. He is now serving nine years in prison, and was the focus of an Oscar-winning documentary.

In the 2010s Navalny was actively involved in mass anti-government rallies and the many exposes by Navalny's main political vehicle, the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), have attracted millions of views online. In 2021 the foundation was outlawed as extremist and Navalny has repeatedly dismissed allegations of corruption as politically motivated.

Many of his associates have come under pressure from security services, and some have fled abroad, including former FBK head Ivan Zhdanov, former top FBK lawyer Lyubov Sobol and most, if not all, of the heads of the extended network of Navalny's offices across Russia.

Navalny's right-hand man Leonid Volkov left Russia when a money laundering case was launched against him in 2019.

Opposition to the war

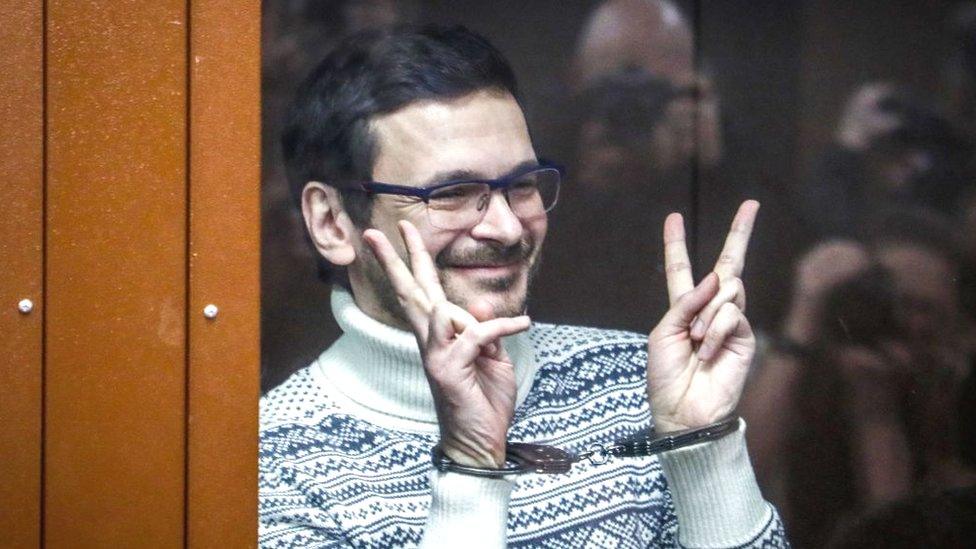

Another key Putin critic behind Russian bars is Ilya Yashin, who has been sharply critical of Russia's war. In a live stream on YouTube in April 2022, external, he urged an investigation into possible war crimes committed by Russian forces and called President Putin "the worst butcher in this war".

That live stream led to eight-and-a-half years in jail for violating a law against spreading "deliberately false information" about the Russian army. The law was rushed through parliament shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

Ilya Yashin was arrested in June 2022 after he condemned suspected Russian war crimes in the Ukrainian town of Bucha

Yashin became involved in politics in 2000 at the age of 17, the year Putin came to power.

In 2017, after years of opposition activism, he was elected head of the Krasnoselsky district council in Moscow, where he continued to voice views critical of the Kremlin.

In 2019, he spent more than a month behind bars for his active role in protests against the authorities' refusal to register independent and opposition-minded candidates for elections to the Moscow city council.

Cambridge-educated journalist and activist Vladimir Kara-Murza has twice been the victim of a mysterious poisoning that left him in a coma, in 2015 and then in 2017. He was arrested in April 2022 following his criticism of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and charged with sharing "fake news" about the Russian military, organising the activities of an "undesirable organisation" and high treason. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison on 17 April 2023.

He has authored numerous articles critical of Putin in prominent Russian and Western media and in 2011 led opposition efforts to secure the adoption of Western sanctions targeting human rights abusers in Russia.

These sanctions imposed by many Western countries are known as Magnitsky acts after whistleblowing lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in a Russian jail in 2009 after alleging fraud by officials.

Fighting for democracy

Kara-Murza was deputy chairman of Open Russia, a leading pro-democracy group set up by fugitive ex-oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky. It was officially designated as "undesirable" in Russia and finally closed in 2021. Open Russia's head, Andrei Pivovarov, is serving a four-year jail sentence imposed for his involvement in an "undesirable organisation".

Kara-Murza may be facing a long prison sentence but at least he is alive, unlike close friend and key Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov.

Boris Nemtsov was shadowed by an agent linked to a political assassination team for almost a year before he was shot dead

Before the Putin era, Nemtsov served as governor of Nizhny Novgorod region, energy minister and then deputy prime minister, and he was also elected to Russia's parliament. Then he became increasingly vocal in his opposition to the Kremlin, and published a number of reports critical of Vladimir Putin and led numerous marches opposing him.

On 27 February 2015, Nemtsov was shot four times as he crossed a bridge outside the Kremlin, hours after appealing for support for a march against Russia's initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

Five men of Chechen origin were convicted of Nemtsov's murder, but there is still no clarity as to who ordered it or why. Seven years after his death, an investigation revealed evidence that in the months running up to the killing, Nemtsov was being followed across Russia by a government agent linked to a secret assassination squad.

These leading opposition figures are just a few of the Russians targeted for showing dissent.

Since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, independent media in Russia has seen further restrictions or threats. News channel TV Rain has had to move abroad, joining news site Meduza which had already left Russia. Novaya Gazeta remains in Moscow but has stopped publishing its newspaper. Others like talk radio station Echo of Moscow were closed by authorities.

Countless commentators have gone into exile, like veteran journalist Alexander Nevzorov, branded a "foreign agent" in Russia and sentenced to eight years in jail in absentia for spreading "fakes" against the Russian army.

But you do not have to have an audience of millions to be targeted. In March 2023, Dmitry Ivanov, a mathematics student who ran an anti-war Telegram channel, received an eight-and-a-half year prison sentence - also for spreading "fakes" about the army.

Meanwhile, single parent Alexei Moskalev was given a two year jail term for dissent on social media following an investigation sparked by an anti-war picture sketched by his 13-year-old daughter at school.

It took Vladimir Putin more than two decades to ensure no formidable opponents were free to challenge his power. If that was his plan, it's worked.

- Published24 March 2023

- Published16 February 2024

- Published28 March 2022