Amnesty: Colombian women treated as 'war trophies'

- Published

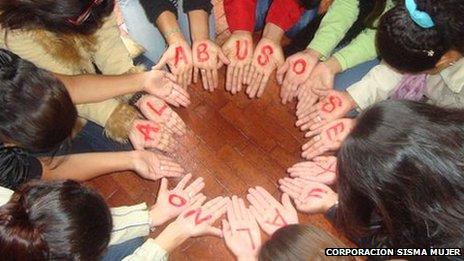

Campaigners are calling for an end to sexual abuse in Colombia

Colombians have had to endure a long list of human rights abuses such as kidnapping, torture and forced displacement over nearly 50 years of civil conflict.

But one of the least acknowledged and addressed abuse is the use of sexual violence against women by the different armed groups, says a report by human rights organisation Amnesty International, external.

"It still is an invisible problem… the last taboo of Colombia's armed conflict," Susan Lee, Amnesty's Americas director, told the BBC.

Amnesty's report, released seven years after the organisation first raised the issue, says the Colombian authorities are not doing enough to guarantee justice for women and girls who have been raped and sexually abused by rebels, paramilitaries, soldiers and police officers.

"All armed groups treat women as trophies of war," said Ms Lee.

"They use sexual violence to punish them when they believe they are not accepting their control, or if they believe their families collaborate or sympathise with the enemy.

"Sexual violence is often used to scare and force the migration of the civilian population."

Intimidation

Amnesty is pressing the Colombian government to take more decisive action to bring those guilty of sexual abuse to trial and to make reparations to the survivors.

Their report contains testimonies of women who have been raped - accounts that tell of constant intimidation and state institutions unresponsive to their plight.

Shirley (not her real name) was only 17 when a paramilitary group dragged her from her village in Antioquia to take her to their base, where she was kept hostage and repeatedly raped.

"I couldn't even tell when I was having my period, because I bled all the time. There were so many men," she said.

Her ordeal lasted for three months in 2005 until she managed to escape.

In December 2008, despite the constant death threats against her and her two children, Shirley made a formal accusation, "so people would know this sort of thing happens".

The decades of violence have marked Colombia

Prosecutors opened an investigation and she was offered protection.

But the investigation did not progress and, in a shocking and bizarre twist, the protection offered by the state required her to share safe houses with several of her rapists, who had been demobilised as paramilitaries two years earlier.

According to Amnesty, Shirley identified more than 35 of the men that abused her sexually.

"But ask me how many are in jail because of what they did to me - none.

"Honestly, there is no justice. Not for me."

Other testimonies included in Amnesty's report incriminate rebels, soldiers and police officers.

The forced recruitment of girls by rebels and paramilitaries is also common.

They act as fighters, messengers or cooks, but some are clearly also recruited for sexual purposes or to be used as bait to lure young men into the conflict.

"We've been told that the girls who belong to the Farc are really beautiful and that they are the ones charming the local lads so they join them," said Sandra Vargas, who heads a non-governmental organisation, Casa Amazonia, based in Putumayo.

And even though men in uniform do not always have to resort to physical violence in this poor, rural department of the Amazon region, "consensual" relationships are often formed with a backdrop of violence.

According to Ms Vargas, many of the local girls "fall in love" with soldiers or guerrillas because they are seen as their only possibility for a better life.

"In Putumayo there's no university, there's nothing, there's no future," she said.

"The rural areas are completely militarised. The army bases are just 100 metres away from schools. (The soldiers) might not force the girls into a relationship, but what other options do they have?"

In turn, the soldiers often use the girls as informers, Ms Vargas said.

"And because of those relationships the girls and their families often become targets. Many have to migrate because of it".

Fear of retaliation

This situation is found in other parts of Colombia.

And whether it involves domestic violence, sexual abuse or under-age sex, those responsible are unlikely to be accused, much less tried.

There have been repeated calls for more to be done to tackle impunity

Fear of retaliation is part of the problem.

But perhaps a bigger problem is that when women muster the courage to report a case of rape or sexual violence, these are rarely effectively investigated, let alone brought to trial, as Shirley's case illustrates.

"Very few of those who committed crimes of sexual violence during the 45 years of conflict have faced justice," Amnesty's report says.

And on the rare occasions when this happens, the cases are seen as common crimes and not as war crimes or crimes against humanity as they should be, Susan Lee told the BBC.

"Rape is an international crime when it's practised in a systematic and generalised way", Ms Lee said. "And that is what's happening in Colombia."

Ms Lee said that Cristina Plazas Michelsen, who advises President Juan Manuel Santos on gender equality, had assured her the government was committed to addressing the problem, and considered it a priority.

These promises now needed to be translated into action, Ms Lee said.

"If Colombia is unwilling, cannot or doesn't want to secure justice in these cases, then international courts, such as the International Criminal Court, could have a role to play."

- Published19 July 2011

- Published30 August 2011

- Published10 August 2011

- Published18 June 2011

- Published29 August 2013