Haiti's cholera row with UN rumbles on

- Published

Nearly 500,000 people in Haiti have contracted cholera during the outbreak

Lawyers representing thousands of cholera victims in Haiti have threatened to take the United Nations to court in the United States, unless the international body responds to a petition for financial compensation.

It is part of a campaign that centres on the extraordinary possibility that the UN - widely seen as a force for good around the world - may have brought cholera into Haiti and as a result may be responsible for nearly 7,000 deaths from the disease.

The UN is being asked to pay $100,000 (£65,000) to the families of those who died and $50,000 (£32,500) to each of the people who fell sick but recovered.

In addition there is a "class action" saying the UN should stop the cholera by rebuilding Haiti's decrepit water and sanitation infrastructure.

If met in total, the claims could cost the international body many billions of dollars.

Cholera is a disease that spreads through human waste and infected water.

Victims can die within hours of the disease taking hold if they don't get treatment. The main symptom is catastrophic dehydration through diarrhoea and vomiting.

'Dire conditions'

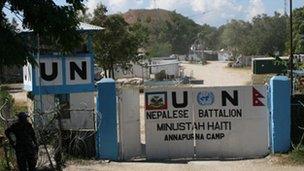

My journey here began in the pretty mountaintop town of Mirebalais, source of the original infection.

No-one contests that this is the area where the outbreak began last October. But where exactly?

The cholera outbreak has triggered ongoing protests against the UN in Haiti

The mayor of the town, Lochard Laguerre, has no doubts: "We know that sanitary conditions in the Nepalese UN camp just outside town were dire," he told me.

"They were dumping their sewage near the river and we know that people die from cholera in Nepal. I told the UN commander in the camp about our concerns a week or so before the first outbreak began."

Inside the Mirebalais UN camp, the current officer in charge, Lt Col Tek Chand of the Nepalese army, contested the mayor's account.

"It's impossible. It didn't start here," he said.

Lt Col Tek Chand was not in charge of the camp when the outbreak began - another Nepalese officer was here.

"There has not been a single case of cholera in this camp," he insisted.

In the camp, technicians were monitoring a new, modern sewage treatment plant recently installed by the UN.

At the time of the cholera outbreak, however, the Nepalese had a contract with a Haitian waste-disposal company that was dumping raw sewage into an open pit outside the camp.

A report by independent experts commissioned by the UN in New York said sanitary conditions at the camp in Mirebalais were insufficient to prevent the spread of infection into the Artibonite River - Haiti's biggest.

The experts' report also said the strain of cholera that hit Haiti was similar to an Asian strain.

Before this outbreak, the experts said, Haiti had not had cholera for nearly 100 years.

'Fingers pointed'

In the capital Port-au-Prince the UN's head of Humanitarian Affairs in Haiti, Nigel Fisher, said the response to the petition was in the hands of lawyers at the UN Secretariat in New York.

But he told me; "I think we all regret the breakout of this thing and I don't think the UN has ever denied the possibility [that it could have been at fault]."

"However I would like to know with some certainty what the source was," he added.

He said that describing it as an "Asian strain" was not helpful.

"The cholera strain we have in Haiti is the same as the one they have in Latin America and Africa. They all derive from Bangladesh in the 1960s so they are all an Asian strain."

He said every moment he spent trying to establish the exact cause of the outbreak was time he was not spending with his humanitarian team tackling the crisis that was still taking lives.

"Fingers are being pointed", Nigel Fisher accepts, "and in the court of pubic opinion in Haiti, the UN is already guilty".

He was certainly right there. Every single Haitian I met during my two week visit was convinced the UN was responsible.

A protest by about 2,000 people was held outside the UN base in the coastal town of Saint Marc.

"Down with the UN," people shouted and sang, "they brought us cholera."

"I'm here because my father died of cholera," said one of the protesters, Pierre Filsmichel.

"My dad left seven children and a wife. He was the breadwinner of our family, and because of cholera he is now dead. We ask for compensation for all the cholera victims."

There are technical question marks around the culpability of the United Nations in this affair.

Although some scientific experts say the Nepalese base was the source of the cholera, others say they cannot be certain.

The UN says it is possible that its forces brought cholera to Haiti, but it is not scientifically proven

A senior UN official, who requested anonymity, pointed out that it was possible for someone to be a cholera carrier without knowing it.

If this had been the case, the UN official said, the source could have been either an unknowing Nepali - or an unknowing Haitian, or anybody else in the country.

Another UN official, who also asked not to be named, said that following a series of internal reports, seen by most senior UN managers, "everyone knew the sanitary situation in the Nepali base was deplorable".

The legal case currently takes the form of a petition under civil law asking the UN to set up a joint UN/Haitian Government commission to hear the cases.

If the civil case is not heard by the joint commission soon, the lawyers say, they will take the matter to court in the United States.

You can hear Mark Doyle's full report Who is responsible for the deadly cholera outbreak in Haiti? by listening to the Assignment programme on the BBC World Service on Thursday 15 December at 09:05 GMT.

- Published10 December 2011

- Published25 August 2011

- Published16 March 2011