Colombia peace prospects echo faintly in conflict zone

- Published

Reaching El Chirriadero means relying on sure-footed mules

Representatives of the Colombian government and the main leftist rebels, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), are set to begin talks this week in Norway, seeking an end to their long-running conflict. But how are the peace moves affecting the people who live in the midst of the violence?

The slope is so steep that I feel like getting off my mule. But maybe that's not such a good idea.

After all, she is the one who really knows this trail, which goes deep inside the mountains of Cauca, into the heartland of the Colombian armed conflict.

We have been riding for hours, in a landscape of steep green hills and deep canyons that disappear into the horizon.

And I know that behind these mountains there are still more mountains and, eventually, the Pacific Ocean.

I have many times described this south-western region as a key corridor for drug trafficking and one of the strongholds of the Farc, the Marxist guerrilla group that has been fighting the Colombian state for 48 years.

And now I'm here to find out what people think about the peace talks set to begin in Oslo.

"I really don't know much about it," says Celimo Zambrano, the Indigenous Mayor in charge of El Chirriadero.

Peace talks between the Colombian government and Farc rebels are set to begin by 17 October

"Maybe the indigenous governor of the region [knows more about it]."

El Chirriadero has no electricity, drinking water, and the closest road is five hours away by mule.

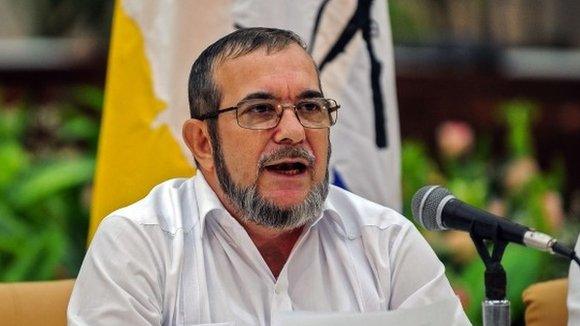

Most Colombians only heard about this small hamlet when the Farc leader, Alfonso Cano, was killed by the Colombian military in the neighbouring hills last year.

It has subsequently emerged that Mr Cano had been discussing, via intermediaries, with Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos the possibility of a negotiated peace.

Military strength

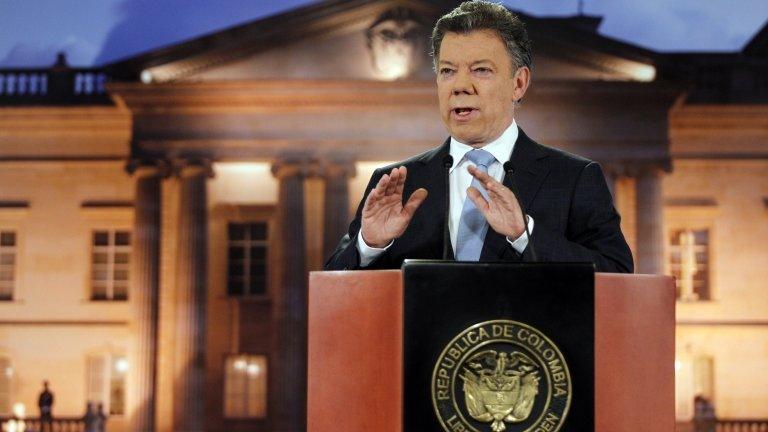

President Santos has said that he made it clear, from the beginning of these contacts, that he would not stop military operations against the rebels until a final agreement was signed.

By doing that, he wants to stop the rebels from using the peace process to regroup and strengthen as on previous occasions.

And the Colombian government certainly does not want to lessen the military pressure on the rebels, believing this is what brought the Farc to the negotiating table.

"I am certain that it is one of the reasons we are negotiating now," President Santos has said.

In El Chirriadero, very little remains of the small house the Farc leader once used as a hide-out.

For local people, talk of peace seems very far away

The craters left by the heavy bombing that announced the arrival of the airborne commandos can still be seen amid the coffee trees now growing in the area.

Over the past 10 years, a much stronger air force has given the Colombian army a clear military advantage.

But, by itself, aerial power is not enough to secure control of large, remote and difficult areas such as northern Cauca.

The guerrillas are still here. As we travel around the area, we know they're watching us.

And the lack of a ceasefire also means the local civilian population continues to be caught in the crossfire.

Dreams of peace

On our way here, we came across some 400 displaced men, women and children, who had just left their villages because of the continuing clashes.

In these mountains, the sounds of conflict drown out any echo of the forthcoming peace talks.

"That was news in the big cities, not here," says Edwin Salazar, a teacher in a rural school close to El Chirriadero.

"They talk about it over there, not in Cauca province," says Sixto Pilcue, from another neighbouring settlement.

Moritz Ehrmann, from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), says that such attitudes appear common in this remote rural area.

Local people do not know much about the peace moves, he tells the BBC.

"So, when you ask them if the [prospect of] peace negotiations has changed anything in their daily lives, they of course tell you that nothing has changed."

For those involved in the peace discussions, the main debate revolves around the possibility of Farc fighters benefiting from an amnesty and participating in politics.

Few Colombians like this idea, but according to opinion polls, a majority do support dialogue.

And the inhabitants of the mountains of northern Cauca are no exception.

"We hope it works. That's what all Colombians and us are hoping for - no more war," says Mr Pilcue.

"What's our dream? To live in peace, to be able to work and to be here without problems, without having to worry about being in the middle of a conflict," says Mr Salazar.

- Published24 September 2015

- Published29 August 2013

- Published7 September 2012

- Published28 August 2012

- Published7 August 2012