Is explicit funk carioca Brazil's new feminist movement?

- Published

The funk scene is changing in Rio, but by how much?

With its distinctive sound and often pornographic lyrics the funk music sound of Rio de Janeiro's shanty towns - funk carioca - used to be a male-dominated world.

Born in the 1980s in Rio's poorest neighbourhoods, the music was inspired by Miami bass - a version of hip hop. Songs were based around themes such as poverty, race and sex.

In the past it used to thrive in some areas dominated by drug traffickers, and parties were often attended by heavily armed men.

But now in a striking change, funk carioca is being adapted as a voice for feminism among working-class women.

There has been a big increase in the number of female funk artists - funkeiras - in recent years.

Their music talks as explicitly about sex as that of the funkeiros, the male funk artists. They defend sexual equality and say they want to break with the myth that a man has power over a woman's body.

Some of the terms widely used to refer to women in funkeiro lyrics are "cachorras", or dogs, "preparadas", ready for sex, or "popozudas", big bottom.

The implication is that women play a servile role in bed and in life in general.

Feminist impact

As funkeiras increasingly dominate the scene, the perception about women's role in funk and in society is also changing.

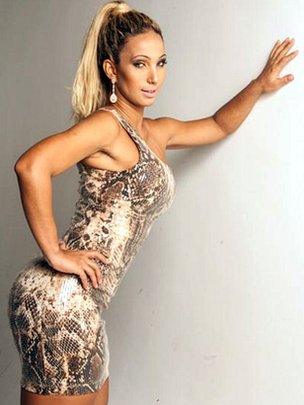

Valesca Popozuda says she sings about subjects important to women

"Funkeiras are empowering poor women with their songs and breaking with the fantasised image of Brazilian women, generally pictured as well behaved," says Ronaldo Lemos, director of the Rio Institute for Technology and Society.

"Their music, sung for lower-class women, is reaching a much wider audience and improving the debate over women's position in society," he adds.

One of the first female singers to compose lyrics with a feminist approach was Valesca Popozuda.

She started her career eight years ago as the vocalist and founding member of the group Gaiola das Popozudas, Cage of Big Bottomed Women.

The group gained national recognition with songs containing highly sexualised language that also promoted gender and sexual equality.

In one of her group's biggest hits, Now I Become A Whore, Valesca talks about a woman who used to be beaten and cheated on by her partner and took revenge on him by finding a lover.

The singer told the BBC she did not expect her music to have a feminist impact but is happy with the outcome.

"I noticed I was attracting more male fans than female and that upset me a bit," says Valesca.

"So the way I found to make women like my music was to sing about topics that were important to them, like equality between men and women and the notion that their body belongs to them and that they can do what they want with it."

'A joke'

Ronaldo Lemos believes songs like those sung by Valesca also reflect the social changes taking place in Brazil, where 40 million people have been lifted out poverty over the past decade.

Explicitly sexual dancing and lyrics still dominate

"Female singers are a mirror of the diversity we find across the Brazilian population, full of totally independent women, who are real fighters, mothers and much of the time the breadwinner," he said.

"Such a woman doesn't want to be seen as a sexual object because this is not the reality."

The explicit content of Valesca's music, seen as vulgar by many, sparked a debate recently in Brazil after she became the theme of a Master's dissertation.

Mariana Gomes, a post-graduation student at Universidade Federal Fluminense in Rio, is considering how women are gaining a new voice through funk.

But journalist Rachel Sheherazade, of TV network SBT, said on air and later in her blog that the link Ms Gomes is trying to establish between funk and feminism is "a joke".

Valesca says she cannot please everyone with her work and challenges criticism that her songs are obscene.

"When a funkeiro talks about sex and going out with many women it is not an issue. So why can a woman not write similar songs about the female side of the story?" she questions.

Polarised views

Feminist writer Lola Aranovich believes the songs which advocate women's entitlement to express their sexuality freely are very positive, especially for poor women who are still forgotten by the state.

"It is better to have some power than none," she says.

.jpg)

Funkeiro Mr Catra doubts feminism can take over funk carioca

On the other hand, she points out that the choreography performed by funkeiras tends to focus on buttocks and breasts.

Valesca Popozuda is herself named after the size of her (surgically enhanced) bottom. Each buttock contains 550 millilitres of silicone and is insured for 5m reals (£1.4m). She also has breast implants.

This, says Ms Aranovich, "is obviously not feminist and turns the woman into merchandise", describing the message that women should have surgery to maintain or boost their appearance as "very negative".

The trend has not gone unnoticed by Brazil's male funkeiros.

The artist known as Mr Catra, whose own songs often contain highly sexualised language, says he recognises the growing feminist message in the funk scene. However, he believes the women are running a risk.

"If women start cheating on men and kissing different guys on the same night, they will find it hard to find a husband," says the singer, who currently has three different partners and describes himself as "the biggest feminist he knows".

Malu Machado, a 22-year-old student in Rio, says those kind of attitudes are outdated and do not reflect the way women live their lives today.

"I notice women feel more liberated and identify themselves with the songs," she says.

"They feel they can do whatever they wish with their sexual lives and are not concerned about other people's opinions."

- Published23 October 2013

- Published6 August 2013

- Published9 November 2010