Amazon rainforest fires: Ten readers' questions answered

- Published

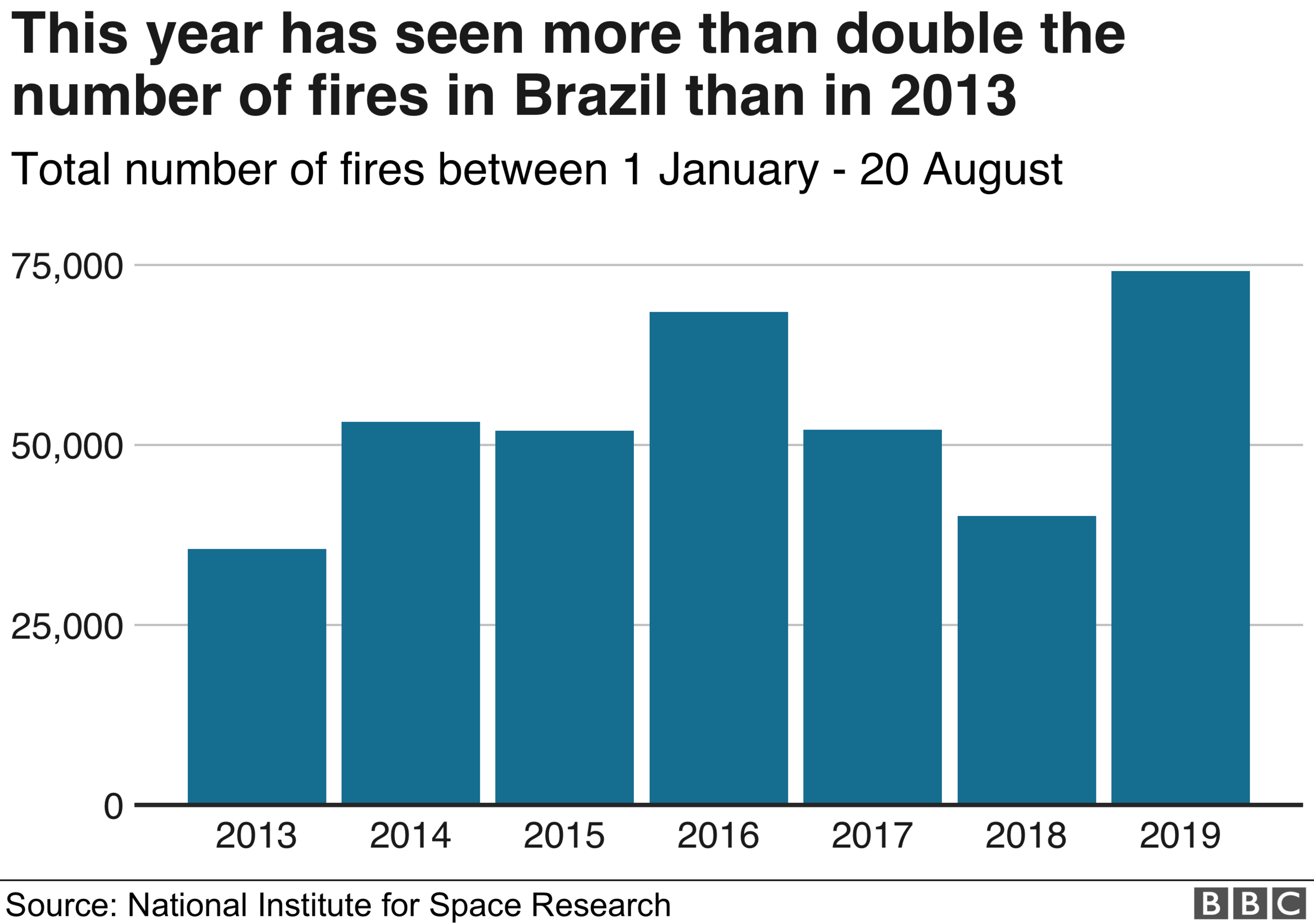

Inpe said it had detected more than 72,000 fires so far this year

Swathes of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil are on fire.

The sky in São Paulo turned black due to smoke drifting from the fires 2,700 km (1,700 miles) away. Politicians and environmental activists are taking a stand against Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, blaming the fires on his policies.

But it's a complex story, and online discussion of it has been riddled with misinformation, misleading photos and errors. We asked you to send us your questions on the Amazon fires, so we could fill in the gaps and clear up some common myths.

We chose a sample of the many questions we received and where we didn't know the answer, we enrolled the experts.

1) Why are there fires? Is it Bolsonaro's men doing it to clear rainforest for mining/farming etc? - Alex

Brazilian journalist Silio Boccanera argues that some fires at this time of year - the dry season in Brazil - are to be expected. But many of the fires burning through the Amazon are believed to have been started deliberately.

President Bolsonaro has not condemned deforestation and supports clearing the Amazon for agriculture and mining.

"So it's a combination of natural phenomena with locals feeling comfortable enough to do it because the government has not made any effort to prevent it," Mr Boccanera says.

Smoke rising through the rainforest

He thinks that smaller groups of people are more responsible for starting the fires than big corporations selling beef and soy, which could run the risk of being boycotted.

Although the big corporations are not innocent, they are better informed, he says.

But smaller groups - who benefit from destroying areas of the forest for farming - have gone ahead because they have not been stopped by authorities, Mr Boccanera explains.

Although deliberate fire-starting has always been a problem, it has never been seen to this extent. Mr Boccanera says perpetrators now know that if they are caught, they won't be punished.

2) The number of fires seems like a bad metric, because the size of fires varies. Is there year-on-year data on the total area affected? - Peter

This is a fair point. On 20 August, Brazil's satellite agency said there had been an 84% increase in the number of fires compared with the same period in 2018. It's the highest number since 2010, but significantly less than in 2005 during the same period, when the number of fires was at its highest.

This year, the satellite agency detected more than 74,000 fires in Brazil between January and 20 August. Most of those were in the Amazon, and the New York Times reports most of those fires were on land already cleared for agricultural use.

But does this mean more land is being burned than ever before? After all, we could be looking at tens of thousands of tiny fires.

The truth is we don't know yet, but the evidence points towards more land being consumed by fire.

We don't have the full picture at the moment, partly because many fires are still burning. We asked Copernicus, the European Union's earth observation programme, and they said the best way to assess how destructive these fires are is to look at how much carbon dioxide is being released.

So far this year, the equivalent of 228 megatonnes has been released, according to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. This is the highest level since 2010.

At some point in the future, there should be more detailed satellite information about how much land had been burned, but that information isn't available yet.

3) What's being done to stop the fires? - Paul

President Bolsonaro is coming under growing political pressure to end the burning of the Amazon - France's President Emmanuel Macron even threatened to scrap a huge trade deal between the European Union and South America as a result.

But warnings by themselves don't put out fires, and a few days after the satellite data was revealed, Brazil's government stepped up its response.

Mr Bolsonaro has called in the armed forces, who have more resources to tackle the fires, including the use of helicopters and aeroplanes to drop water.

However, journalist Silio Boccanera believes the attitude at the top of government needs to change. Before, people believed deforestation needed to be prevented. But now "people are burning without fear", he says.

4) The coverage on this subject has only come to light recently because of the #PrayforAmazonas and #PrayforAmazonia hashtag. Why have you not reported it? - Jake

We and other news outlets published several reports this summer about the extent of deforestation in the Amazon - here's one report we wrote on 2 July, another from 20 July and another from 2 August.

But the extent of the fires has only recently become clear. It was not even being reported very widely in Brazil.

The first real sign vast burning was taking place came when a daytime blackout, caused by smoke from the Amazon, hit Sao Paulo on Monday, 19 August.

We first published an article a day later, just a few hours after our colleagues at BBC Brasil, and we've kept updating it ever since.

Worldwide protests over Brazilian government inaction on Amazon fires

The #PrayforAmazonas hashtag was first used in the early hours of Wednesday, UK time. This, and others such as #prayforrondonia have become trending topics around the world.

5) Is this a natural, healthy way the forest self-clears for new growth? - Lucy

As Lucy suggests, there is a case to be made that some fire-adapted forests benefit from fires - they can help clear the forest and allow trees space to grow stronger.

But this is not the situation right now in the Amazon, says Yadvinder Malhi, Professor of Ecosystem Science at the University of Oxford. "These are fires that we are concerned about," he says. The humid forests of the Amazon have no adaptation to fire and suffer immense damage. Almost all fires in humid forests are started by people.

He believes the driving force behind the fire is human rather than natural.

While statistics show that 2016 also saw a significant number of fires in the Amazon, this was considered a "drought year"- when there is naturally less rain so the forest is drier and therefore more fire-prone.

But 2019 has not been a drought year. Professor Malhi says there is such a large number of fires because people have lit them.

6) How quickly does the Amazon rainforest regenerate after a fire? - Emily

"The forest takes around 20-40 years if it's allowed to regenerate," says Prof Malhi.

But any fires that are currently burning will leave the surviving trees more vulnerable to drought and repeated fires.

Prof Malhi is worried that if the Amazon is hit by fires every few years large parts of it will shift to a degraded shrubby state.

"Once you've had multiple fires there's the chance of permanent damage," he says.

7) If this current trend were to continue at its present rate, how long would the Amazon rainforest area survive? - Christopher

"We are at an early stage where we can still do lots to save the forest," says Prof Malhi. About 80% of the Amazon is still intact.

But he says that climate change and deforestation are a dangerous combination. A reduction in rainfall would create dry conditions for fires to spread.

If 30-40% of the Amazon was cleared, then there would be a danger of changing the forest's entire climate, he says.

In the years before 2005, Brazil had an extremely high rate of deforestation.

Photos from 2003 showing aggressive deforestation in Brazil

"If Brazil were to return to that, it would take around 50-60 years to deforest 40% of the Amazon," Prof Malhi says. "But in eastern and southern Amazonia it would take only 20-30 years to reach that threshold."

8) What percentage of oxygen does the Amazon supply? - Tom

Our colleagues from BBC Reality Check spent a whole day getting to the bottom of this.

Many claim on social media that the Amazon produces about 20% of the world's oxygen. It's widely quoted - by campaign groups and well-known figures, including Emmanuel Macron and footballer Cristiano Ronaldo.

But academics say this is a very common misconception, and that the figure is less than 10%.

Oxygen is released by plants during the process of photosynthesis, where carbon dioxide and water are converted into energy in the form of carbohydrates using sunlight.

A large proportion of the world's oxygen is produced by plankton, explains Professor Malhi. He says of the oxygen produced by land-based plants, about 16% comes from the Amazon.

But this isn't the whole story. In the long run, the Amazon absorbs about the same amount of oxygen as it produces, effectively making the total produced net zero.

Professor Jon Lloyd from Imperial College London says although the Amazon produces a lot of oxygen during the day through photosynthesis, it absorbs about half of it back through the process of respiration to grow. Further oxygen is used up by the forest's soil, animals and microbes.

The fires are also emitting carbon monoxide - a gas released when wood is burned and does not have much access to oxygen.

9) Will the smoke from these fires have an effect on global weather in future months? - David

Prof Malhi says the immediate effect of the fires will be on the climate of South America. Reduced rain fall is likely, leading to a more intensive dry season.

"The carbon emission could contribute to global warming," he adds, but the longer term global impact is "more difficult to pin down".

In the long-term, scientists have told the BBC the fires could make the Paris climate target more difficult to achieve. The global treaty aims to limit average temperature rise to well below two degrees Celsius to avoid dangerous climate change.

10) How are these fires affecting the indigenous people? - Samantha

In just one week in mid-August, 68 fires were registered in indigenous territories and conservation areas, the majority in the Amazon, according to Jonathan Mozower from Survival International, which campaigns for indigenous rights, external.

"It's hard to overstate the importance of these forests for indigenous peoples," he says. "They depend on them for food, medicines, clothing and a sense of identity and belonging.

But the incentives to steal these resources are high and "sadly it's not a question of one or two rogue actors", Mr Mazower says. He says this could be the "worst moment for the indigenous people of the Amazon" since the military dictatorship, which ended in the 1980s.

Members of Brazil's indigenous Mura tribe vow to defend their land

This article initially stated there was a record number of fires in Brazil this year. After more satellite data was made accessible, it has been updated to reflect the fact the fires are instead the worst since 2010.

- Published30 August 2019