Salvador Cienfuegos: From 'Godfather' on trial to free man

- Published

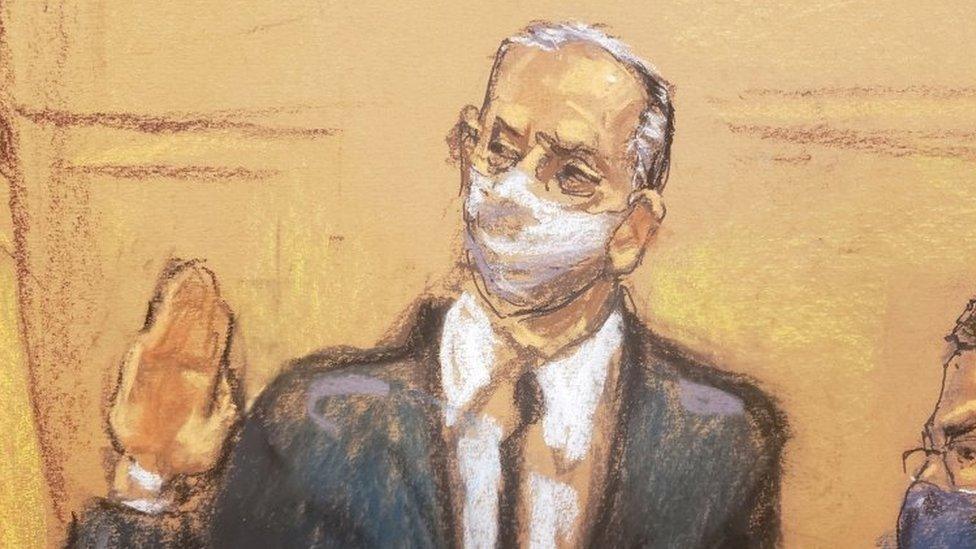

The ex-defence chief was arrested at Los Angeles airport last month

In unsealed court documents in October, US prosecutors claimed former Mexican Defence Minister Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda was also known as "the Godfather".

His mafia-don pseudonym reflected his alleged standing at the top of a pyramid, the prosecutors argued, which incorporated the armed forces, the Mexican government and the "extremely violent" H-2 drug cartel.

General Cienfuegos was accused of using his high-ranking position to provide the cartel with unique protection by tipping them off to military operations against them and directing the army and its resources against their rivals.

He was also accused of more prosaic drug-trafficking crimes, such as receiving multi-million-dollar bribes and smuggling heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and marijuana into the US.

The charge sheet - which he denied - was explosive. Gen Cienfuegos was the highest-ranking Mexican official ever to be arrested on drug-trafficking charges. But this was no joint US-Mexico operation or shared investigation involving agents on both sides of the border.

Rather, officials at the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) were so wary of word getting back to their target that the first anyone in the Mexican government heard of the case him was when the 72-year-old former general was detained on his arrival in Los Angeles with his family.

Yet now - to employ the "big-fish" metaphor for drug cartel leaders - those same officials at the DEA and the Department of Justice have just let what was supposedly the biggest catch of their careers back into the water.

As they asked a federal judge in New York to dismiss the charges against Gen Cienfuegos, US prosecutors cited "sensitive and important foreign policy considerations" which they said "outweighed" the government's interest in pursuing the prosecution.

The judge, Carol Bagley Amon, noted that there was an element of "a bird in the hand" in having such a notable figure on such serious charges in her court, but ultimately concluded that she had no reason to doubt the "sincerity" of the government's decision.

So, instead of potentially facing a long jail sentence in the US alongside convicted drug lord Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzmán, Gen Cienfuegos returned to Mexico as a free man.

The US Department of Justice says that it has provided Mexico with evidence and has committed to co-operation

Given the political shockwaves his arrest had caused in the corridors of power in Mexico, one could almost hear the sighs of relief emanating from government offices and barracks around the country.

"If crimes have been committed, it is now in the hands of the attorney general's office to investigate, substantiate and sustain them in this case", said Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard. Anyone found responsible, he continued, should be "processed before the Mexican authorities and brought before Mexican justice".

That is the same justice system, of course, which US prosecutors considered too corrupt and riddled with leaks to entrust with the basic information of what they were working on.

The immediate conclusion drawn by many observers was that the decision by Attorney General William Barr to drop the charges was a form of quid pro quo between Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador - also known as "Amlo"- and the Trump administration.

Mr López Obrador - who while running for the presidency was openly critical of Donald Trump - has surprised many in Mexico by his willingness to accommodate his US counterpart. But not everyone is convinced this case being dismissed amounted to a favour being called in.

President Lopez Obrador visited President Trump at the White House earlier this year

"I would just take it for what was said," argues Ana Maria Salazar, a former US deputy assistant secretary of defence for drug enforcement policy and support. "That they were dropping the charges based on larger interests and co-operation in the bilateral relationship. I think that's basically what happened."

"I don't think it was just a quid pro quo for Amlo," echoes Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank. That may be part of the explanation, he says, but the likelihood is that the Mexican president came under "a lot of pressure from the military in Mexico to bring Cienfuegos back and not have him prosecuted in the United States".

Now that the case won't be heard in the US, one can only speculate whether the evidence against Gen Cienfuegos was sufficiently robust to ensure conviction.

It's possible that his lawyers may have been able to argue that any contact he may have made with the H-2 cartel was part of a wider effort to bring down El Chapo Guzmán, who was arrested and extradited to the US while Gen Cienfuegos was in office.

Certainly the political fallout of the drug-trafficking trial of a former defence minister would have been deeply damaging to officials on both sides of the border. But while the decision to drop the charges speaks a great deal about backroom political considerations over bilateral co-operation, it also attests to the enduring strength of the military in Mexico.

"Amlo has been very pleased with the military's performance in essentially any duty he's asked them to do," observes Roderic Camp, an expert on the Mexican military and professor at Claremont McKenna college in California. "It's no secret that he has basically said that he likes working with the military. His administration will be receptive to appeals that this person be tried in Mexico and not in the US."

It is widely understood that key members of Mexico's top brass were apoplectic about the arrest of their former boss. It has been reported that they even pressured the government into threatening to expel DEA officials from Mexico, an unprecedented step that would have undone longstanding joint security arrangements.

Mr López Obrador has denied that such a threat had been made. But Ana Maria Salazar says there was a "systematic belief within the armed forces" that the DEA's charges were without foundation and placed a significant strain on ties between the two countries.

"This type of prosecution would have had a catastrophic impact on co-operation in counter-narcotics and defending national security interests in both nations," she points out, especially because the Mexican president has given the armed forces, particularly the army, an increased role in tackling organised crime.

You may want to watch:

How Mexican cartels are taking advantage of Covid-19

The apparent protection of Gen Cienfuegos goes against the grain for Amlo's political coalition and his base, many of whom are strong critics of the army - especially over its poor human rights record.

But the president can ill afford to lose the military's support. As well as turning to them to take the lead on organised crime, he has also bestowed new and normally civilian-led responsibilities on the armed forces, from constructing a $3.5bn airport for Mexico City to helping co-ordinate the response to the coronavirus epidemic.

"It's a very strange and a very strained relationship between the armed forces and this Mexican president to say the least," concludes former Clinton Administration adviser Ana Maria Salazar.

Mexico has said it will investigate the charges against Gen Cienfuegos and it is conceivable, of course, that their prosecutors may bring charges of their own.

Certainly the López Obrador administration has prided itself on prosecuting high-profile figures, some once considered untouchable, from the previous administration of Enrique Peña Nieto. They include the former-head of the state-owned energy company Pemex, Emilio Lozoya.

Mr López Obrador is planning to hold a referendum to decide whether to lift presidential immunity, paving the way for corruption charges to be brought against several of his predecessors including Mr Peña Nieto.

Still, Michael Shifter of the Inter-American Dialogue considers it "highly unlikely" that Salvador Cienfuegos will see the inside of a Mexican courtroom, much less a Mexican jail.

"Levels of impunity in Mexico are extremely high and Amlo cares about maintaining and nurturing his relationship with the army," he says.

While Gen Cienfuegos may yet avoid a drug-trafficking trial, his fall from grace has been spectacular. At one point, he was one of the most powerful men in Mexico, as influential within the government as he was within the military. Yet even as he was being honoured with an award from the Pentagon's Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies as late as 2018, the case against him was being drafted by US prosecutors.

Ultimately, then, perhaps what matters most in the Cienfuegos debacle is trust - or lack of it.

An effective cross-border partnership to tackle drug-trafficking is predicated on mutual trust. While that has been in short supply at certain points over the past few decades, strides have been made under recent administrations - largely based on military-to-military relationships.

Gen Cienfuegos' arrest changed that, argues Roderic Camp, and jeopardised an understanding "that took a long, long time to develop among top-ranked officials on both sides".

It seems that the case boiled down to an equation over whether his conviction was worth the loss of trust it would cause - combined with the defendant's presumed capacity to unleash some serious scandal from inside court. In the final analysis, US officials simply decided they had more to gain by handing back "the Godfather" to Mexico.

"The grown-ups in the room with the responsibility of overseeing and implementing one of the most important strategic relationships for the United States probably went to Attorney General Barr and said we have to solve this as soon as possible," Ana Maria Salazar says.

"If not, the impact would have potentially lasted for a decade."

- Published8 October 2020

- Published16 October 2020

- Published24 October 2019