Iran's President Hassan Rouhani boosts power before UN meet

- Published

Hassan Rouhani has made his first foreign trip since taking office, as James Reynolds reports

Hassan Rouhani doesn't fidget. I know this because I spent 90 minutes in the same room as him a week ago in Kyrgyzstan.

Mr Rouhani was in the capital, Bishkek, to attend a regional summit. In contrast to his fellow leaders at the conference table, Mr Rouhani sat still and listened patiently to speeches and statements.

It was hard to know how to interpret his stillness. It may be that he was quietly reflecting on the series of moves which appear to have strengthened his position.

Mr Rouhani took office in August with a promise to end confrontation and engage with the rest of world.

Iran's 'CEO'

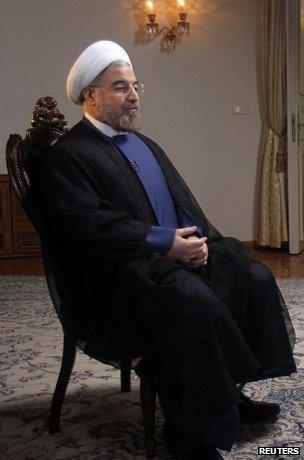

Calm posture: President Rouhani during an interview with the US television network NBC in Tehran

But a president in Iran has little formal power. So, an Iranian chief executive has to rely on his powers of persuasion to get things done.

Above all, the president has to make sure that no distance opens up between him and the country's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. With this in mind, the new president took action.

On 6 September, the president appointed his Foreign Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, as Iran's nuclear negotiator (a job once held by Mr Rouhani himself).

Mr Zarif is an experienced, English-speaking diplomat who reports directly to the president.

This strengthens Mr Rouhani's ability to control nuclear negotiations. Talks in recent years largely excluded the-then president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Having secured control of nuclear diplomacy, Mr Rouhani decided to go further.

On 16 September, he took the daring step of asking the country's powerful Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) to stay out of politics. Under the command of the Supreme Leader, the IRGC has played a dominant role inside Iran.

Power play

A presidential appeal on its own would have meant nothing. But, crucially, the president's call was directly reinforced the next day by the ayatollah himself. In a speech, Mr Khamenei even praised the role of diplomacy and announced that flexibility was no bad thing.

In the course of 10 days, Mr Rouhani had transformed his weak presidential hand. He was now in overall charge of nuclear diplomacy, with a direct mandate from the supreme leader to engage in talks.

Two days later, Hassan Rouhani delivered the first concrete sign of a new start for his country. Iran's most prominent human rights lawyer, Nasrin Sotoudeh, was released from Evin prison along with a number of fellow activists. Mr Rouhani does not get to decide prisoner releases - but it's clear that his influence has had an effect.

Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, alongside Revolutionary Guard members

UN meet

The president was now ready to address the outside world - the United States in particular. His decision to grant his first major interview to NBC, a mainstream US news organisation, shows the focus of his diplomatic efforts.

For Iran, reconciliation with the United States after more than three decades as opponents is the great prize. Some in America share the same view.

"It makes so much strategic sense for both countries," says Stephen Kinzer, the author of several books on US-Iran relations. "Both countries have the desire to calm Afghanistan, to calm Iraq, to calm Syria.

"The reason that Americans have not been able to see the great strategic benefit that could accrue from a closer relationship with Iran is emotion. Emotion is always the enemy of wise statesmanship. If we are now getting to the point where we can get past this emotion, then I think the United States might be in a very positive place. "

The presidents of the USA and Iran are now in direct written contact. President Obama and Hassan Rouhani have exchanged letters.

But their respective administrations say that there are no plans for either man to meet while they are both in New York next week. To many, the excitement of a possible new start is tempered by the memory of previous failures.

"Unfortunately we've been through this before when Khatami became president [in Iran in 1997,]" says John Limbert, a former US hostage in Tehran who now teaches at the US Naval Academy,

"People were very hopeful. And, on this side when Obama became president. But there's always been a frustration - bad luck, bad timing, sabotage or whatever - and things have gotten off track. But, at least so far, people are saying the right things and they're being cautious which is also a good thing."

In a few days' time, Hassan Rouhani will be in the same halls as his pen-friend Barack Obama. The US president will know how to spot his counterpart amid the dozens of presidents who will be in town. Mr Rouhani is the one who sits incredibly still.

- Published19 September 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published16 September 2013

- Published15 August 2013