Mosul: Culture and concerts where IS once reigned

- Published

A Peace Festival was held in Mosul weeks after IS was ousted

For almost three years, while her home city of Mosul was under occupation by so-called Islamic State (IS), Tahani Salih kept a daily diary documenting their crimes.

Tahani, now 27, filled almost 500 pages with her experiences and those of her family and friends, as well as her hopes and dreams for the time when IS would be defeated.

"Just before our neighbourhood was liberated, IS began to harass people and force their way into their homes to carry out searches. One day I took out those hand-written pages and started to reread them, and I was shocked," she said.

"I realised that the content could put my life and my family at risk, as well as people I had mentioned in my diary. So I had no choice but to destroy those papers.

"I sat down, and started to burn one page at a time. Later, I blamed myself for not hiding my diary or burying it in our garden."

Although the diary is gone, Tahani remembers every word of the plans she made. Now IS has been defeated, Tahani is throwing herself into putting them in place.

The young woman - who has been trained and supported by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) - is one of a new group of Mosulite activists who are determined to not only rebuild the city but also help rehabilitate fellow residents traumatised by the events of the last three years.

"There are about 40 of us - we're ambitious, educated, respectable young people who love their city and fellow human beings, and want to have a decent future," she said.

Tahani's own priority is to ensure that young women like herself can get involved.

"We live in a culture in which women think it's improper to speak up, or to work outside the home or lead a campaign, which is not true. I know girls who are very strong and motivated, but are scared of harassment or are being forced to stay at home by their families.

"People need to know that being a girl is not shameful," she continued, arguing that a culture of fear and repression was "the very condition that helped IS come in".

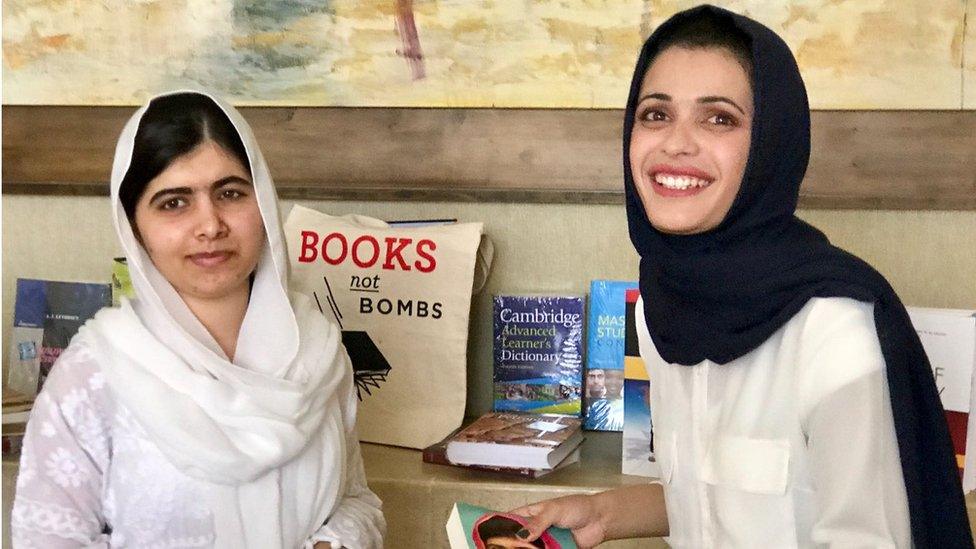

Tahani Salih (R) with Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai in Irbil in July

So when Tahani got involved with an ambitious scheme to restore Mosul university's library, which was destroyed by IS during the occupation, she delighted in encouraging other young women to defy gender stereotypes.

Herself one of the first to enter the bombed-out library, she remembers seeing "a boy approaching a girl carrying five or six heavy books.

"He said: 'No, you don't have to carry that much. It's too heavy for you, just carry what you can.' She said: 'Of course I can carry the books, I've come to do just that. Please do your work and carry books, and I'll carry mine.'"

Live music

Tahani also put together a football tournament for the library project's volunteers, initially forming one for men and one for women, before deciding this looked too much like gender segregation. To her colleagues' astonishment, she mixed the teams together - an unprecedented move that proved successful.

"The next day, they brought the ball, and said: 'Let's play again.' So we did."

Tahani said that it was not just Mosul's physical fabric that needed rebuilding; it was crucial to harness young people's enthusiasm for freedom in the first few months of liberation.

Art and other expressions of culture were banned under IS for three years

"So we started with cultural events - books, music, festivals, colours, painting, photography.

"We wanted to draw media attention to Mosul so that a young person could see his or her image on a global platform and admire themselves and realise their value."

Tahani organised the first concert in the city after IS' defeat, with live music played in front of the university campus.

The University of Mosul was heavily damaged in the fight against IS

"One of the girls took me by the hand and told me: 'Tahani, this is the first time I feel really alive,'" she recalled.

And together with some friends, Tahani set up a Facebook page called Women of Mosul, external, a place where they could air views and share ideas for projects.

Hopes and dreams

The work by young Mosulites like Tahani seems to be gaining some traction. Last month, a day-long peace festival set up by other activists drew a crowd of 25,000 people to the city's main stadium.

But Tahani said there was much more to be done, arguing that true success would come when women felt totally free to walk on the street without wearing hijab, or when a bar selling alcohol could function freely in the centre of the city.

Tahani said people in Mosul "need to know that being a girl is not shameful"

"Only then will I be reassured that the city has begun to truly accept everyone, and accept the world."

That seems a long way away, given the conservative attitudes still dominant in the city.

Many fear that former IS supporters remain in the city, trying to blend into the civilian population.

Tahani acknowledges that she has received threats over her activism, but refuses to be intimidated.

"If I get scared, then I'll have to return to just sitting at home, which I won't accept. There's no way I will go back to that and forget all my hopes and dreams, no matter the price."

The Institute for War and Peace Reporting is a non-profit organisation which supports local reporters, citizen journalists and civil society activists in three dozen countries in conflict, crisis and transition around the world.