Islamic State assassin: How I killed more than 100 people

- Published

Syria has been at war for seven long, deadly years. President Bashar al-Assad's government is fighting both rebel groups and the jihadists of Islamic State. The northern city of Raqqa has been a key battleground for many factions in the conflict. This is the story of how one peaceful protester there got sucked into the spiralling bloodshed, and became a killer.

Warning: This piece contains descriptions of torture which some readers may find upsetting. Some names have been changed or removed.

Khaled did not simply wake up in Raqqa to the smell of death and dust, and decide to become an assassin.

He was sent a special invitation.

Six men were ordered to report to an airfield in Aleppo, in north-western Syria, where a French trainer would teach them to kill with pistols, silenced weapons, and sniper rifles.

They learned to murder methodically, taking prisoners as their victims.

"Our practice targets were detained soldiers from the regime," he says. "They put them in a difficult place so you need a sniper to hit them. Or they send out a group of detainees and ask you to target one without hitting the others.

"Most of the time assassinations are done from a motorbike. You need another person to ride the bike and you sit behind him. You ride next to the target's car - then you shoot him and he cannot escape."

Khaled - not his real name - learned how to follow people. How to "buy" targets he could not reach through those close to them. How to distract a convoy of cars, so a fellow assassin can pick off their mark.

It was a bloody, inhuman education. But in mid-2013, soon after the Syrian army retreated from Raqqa, it suited the leaders of Ahrar al-Sham - a hardline Islamist group striving to rule the northern city and eliminate its rivals.

Rebels claimed near-total control of Raqqa in March 2013

Khaled was one of the group's commanders, in charge of Raqqa's security office.

And yet, he told the BBC, when the Syrian revolution drew its first breaths in 2011 he was a man of peace, "a bit religious, but not too strict", with a job organising pilgrimages.

"It was an amazing feeling of freedom mixed with fear of the regime," he says, recalling the first day he joined the anti-government protests.

"We felt that we were doing something to help our country, to bring freedom and to be able to choose a president other than Assad. We were a small group, no more than 25-30 people."

Khaled says no-one thought about taking weapons to the early protests - "we didn't have the courage for that", but the security forces arrested and beat people nonetheless.

One day, it was him they detained.

"They took me from my house to the Criminal Security Department, then to other departments. Political Security, State Security... and then to the Central Prison where I stayed for a month before they released me.

"By the time I entered the Central Prison I couldn't walk, and couldn't sleep because of my backache."

Syria's anti-government protests began in Deraa in early 2011, triggering a national uprising

Khaled says his most barbaric abuser was a guard at the Criminal Security Department who forced him to kneel before a picture of President Assad, saying: "Your god will die, and he will not die. God dies, and Assad endures."

"His shift was every other day, and when it came I knew I would be tortured.

"He used to hang me from my arms with chains to the ceiling. He would force me to strip, then put me on 'the flying carpet' and whip my back. He would tell me: 'I hate you, I hate you, I want to you to die. I hope you die at my hands.'

"I left his prison paralysed, and when they moved me to the Central Prison inmates were crying when they saw me. They brought me in on a stretcher.

"I decided that if God saved me I would kill him wherever he goes. Even if he went to Damascus, I would kill him."

Khaled was detained after someone recognised him in film footage from anti-government protests

When he was freed from prison, Khaled took up arms against the government. He says he "helped" 35 Syrian army soldiers to defect from the 17th Reserve Division, which was stationed in the country's north-east.

Some of them he kidnapped, selling their possessions to make money for guns.

Sometimes, he says, he joined forces with attractive women to lure "notorious individuals who hurt protesters" with offers of marriage. He spared their lives, but forced them to make defection videos so they could never again serve President Assad. For his first hostage, the ransom was set at 15 Kalashnikovs, or their value in cash.

One man received no such mercy: the guard who tormented Khaled.

"I asked people about [the guard] who worked at the Criminal Security Department until I found him. We followed him home, and took him.

"He told me something that I reminded him of later. When I was in prison, he told me: 'If you leave this prison alive and you manage to capture me, do not have mercy on me' - and that's what I did.

"I took him to a farm near the Central Prison which was a liberated area. I cut off his hand with a butcher's knife. I pulled out his tongue and cut it with scissors. And still I wasn't satisfied.

"I killed him when he begged for it. I came for revenge, so I wasn't afraid.

Khaled bartered his more fortunate captives for Kalashnikov rifles

"Despite all the torture methods I used with him, I don't feel regret or sorrow. On the contrary; if he came back to life again right now I would do the same.

"If there had been an authority to complain to, to say he beats and humiliates prisoners, I wouldn't have done this to him. But there was no-one to complain to and no state to stop him."

Khaled had lost his faith in the revolution. His focus became the daily battle for his own survival. And he would soon find an even darker role in Syria's savage conflict - as an assassin for the jihadist group Islamic State (IS).

'I showed IS a friendly face... then killed them'

Friendship or betrayal, quarrels about tactics, and swings in the balance of power: these caused many of Syria's rebels to switch between factions, sometimes repeatedly.

Against that backdrop, Khaled left the Islamists of Ahrar al-Sham who had trained him as a killer, and joined al-Nusra Front, then the official affiliate of al-Qaeda in Syria.

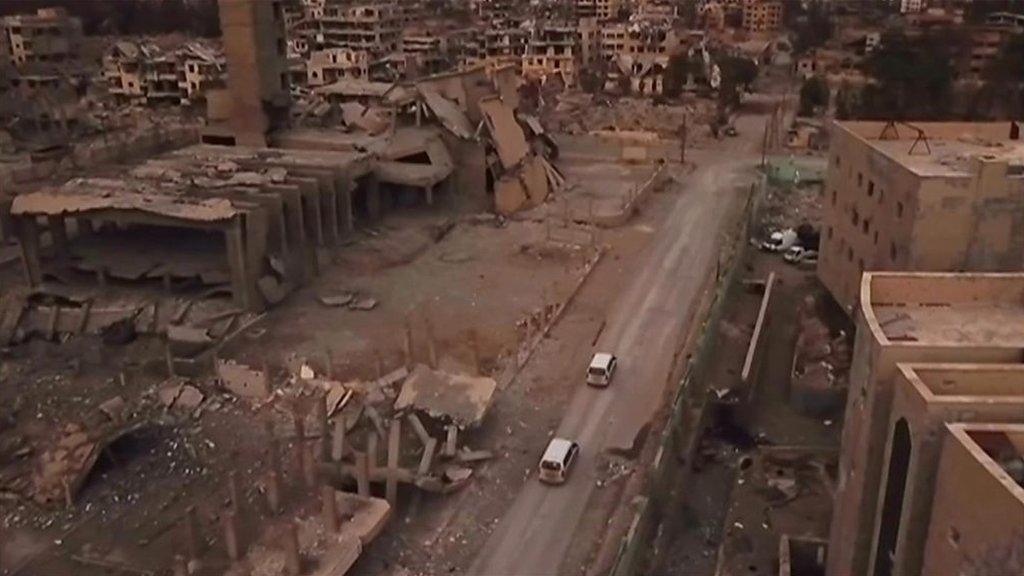

By early 2014, IS - which he and other fighters once mocked as a no-account outfit with paltry numbers - had driven rebel factions out of Raqqa. The city would become the de facto capital of IS's "caliphate".

Black jihadist flags appeared all over Raqqa as IS tightened its grip

Militants terrorised the civilian population through beheadings, crucifixions and torture. "IS would take their property, kill and imprison them for the silliest reasons," says Khaled.

"If you said, 'Oh, Muhammad' they would kill you for blasphemy. Taking photos, using mobiles; these have punishments. Smoking would result in prison. They did everything - killing, stealing, rape.

"They would accuse an innocent woman of adultery then stone her to death with kids watching. I don't even kill a chicken in front of my siblings."

The jihadists bought up senior rebel leaders with cash and high-status positions. Khaled was offered a job as a "security chief", with an office and authority over IS fighters. He understood that refusing would sign his death warrant. So he reached a terrifying personal compromise.

"I agreed," he says, "but with the consent of Abu al-Abbas, a senior al-Nusra leader, I became a double agent. I showed IS a friendly face, but I would secretly kidnap and interrogate their members, then kill them. The first one I kidnapped was Syrian, the leader of an IS training camp.

"I would leak to IS whatever Abu al-Abbas wanted me to leak. Some information was true, to make IS believe me. But at the same time I took secrets from them."

Al-Nusra Front had an obvious motive for spying on IS. It had rejected a merger announced by IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2013, and aligned itself with other rebel groups.

Khaled's decision looked like a death wish, but it was others who died. He says he murdered around 16 people for IS, shooting them in their homes with a silenced pistol.

He says they had sold their religion for money, betraying Ahrar al-Sham and the Free Syrian Army - the Western-backed alliance that first wrested Raqqa from government control.

Khaled says IS sent him to assassinate people in secret (file picture)

One of his victims was an Islamic scholar from al-Bab. "I knocked at the door. He opened it. I immediately went in with a gun pointed at his face. His wife started screaming. He knew that I was coming to kill him.

"Before I said anything he said to me, 'What do you want? Money? This is my money - take whatever you want.' I said no, I don't want money. And I locked his wife in the other room.

"Then he said, 'Take the money - if you want my wife you can sleep with her in front of me, but don't kill me.' What he said encouraged me to kill him."

The IS emirs in Raqqa liked novelty, and routinely killed those they had bribed to replace them with new blood. Sometimes they blamed US-led coalition warplanes for the death; sometimes they didn't bother. Just a month after taking the IS job, Khaled was sure they would come for him soon.

The assassin fled for his life, first by car to the eastern city of Deir al-Zour, and later on to Turkey.

Khaled appears in BBC documentary Syria: The World's War

Asked if he has any regrets or thinks he could one day be prosecuted, Khaled simply says:

"All I thought about was how to escape and stay alive.

"It isn't a crime, what I did. When you see someone pointing a weapon and beating your father, killing your brother or relatives, you cannot keep quiet and no force can stop you. What I did was self-defence.

"I killed over a hundred people in battles against the regime and IS, and I don't regret it… because God knows I never killed a civilian or an innocent person.

"When I look in the mirror I see myself as a prince. And I sleep well at night, because everyone they asked me to kill, deserved to die.

"When I left Syria I became a civilian again. Now if anyone says anything rude to me, I respond - 'As you wish.'"

Khaled was interviewed last year for a documentary - Syria: The World's War - to be shown in the UK on BBC 2 at 21:00 on 3 and 4 May. It will broadcast globally on BBC World News on 26 May and 2 June.

A short guide to the Syrian civil war

- Published2 May 2023

- Published28 March 2018

- Published7 January

- Published14 November 2017

- Published17 October 2017

- Published22 June 2017

- Published6 June 2017

- Published5 March 2016