Lebanon protesters' euphoria gives way to despair

- Published

Tripoli, Lebanon's poorest city, into a hotbed of the demonstrations a year ago

Thousands of young protesters poured into Tripoli's al-Nour Square a year ago for what turned into a massive dance party.

Music blasted round the square, glow-sticks lit up the night sky, and a sea of demonstrators chanted "Thawra, thawra, thawra", which means "revolution" in Arabic.

They wanted jobs, they wanted social services, and they wanted an end to rampant official corruption.

On a balcony overlooking the square was Mahdi Karimeh, who would later be dubbed the "DJ of the Revolution".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"It was the greatest moment of my life," says the 30-year-old computer programmer.

Mahdi's actions were as spontaneous as the hundreds of thousands of Lebanese who demonstrated in cities and towns across the country, demanding the overthrow of their government.

"I was drinking coffee with my friends and I saw people passing by in the street holding Lebanese flags and that's when I had the idea for a concert," he recalls.

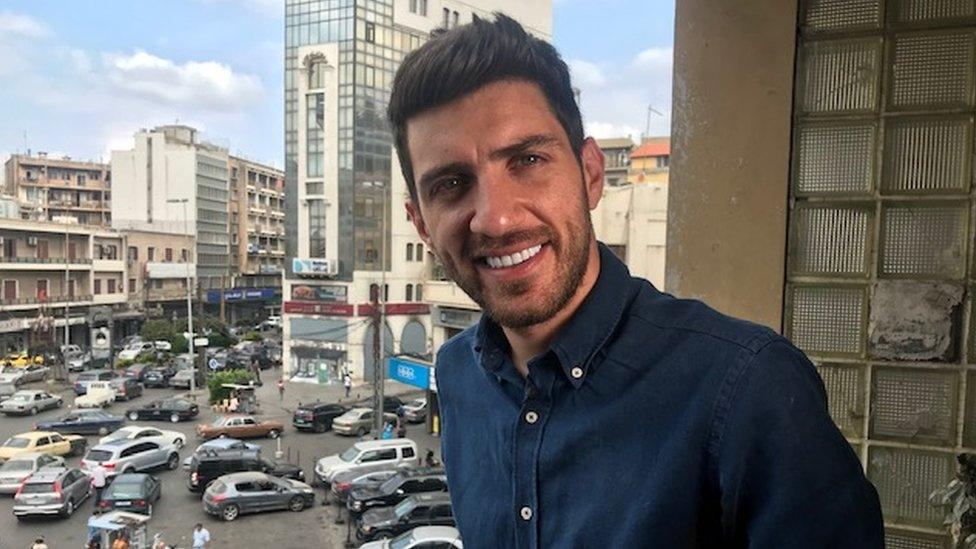

Mahdi Karimeh, dubbed the "DJ of the Revolution", wants the protests to continue

The protesters came from all walks of life and from all faiths - cutting through the sectarian divisions that for so long have dominated Lebanese life.

And for a moment a younger generation believed that lasting political change might just be possible.

Mahdi's DJ sets helped turn Tripoli, Lebanon's poorest city, into a hotbed of the demonstrations.

"It's my first time here since the protests," he says, standing on the balcony where he first set up his turntables a year ago.

"Honestly, I feel nervous but happy at the same time. Just standing here I feel like I'm going to cry."

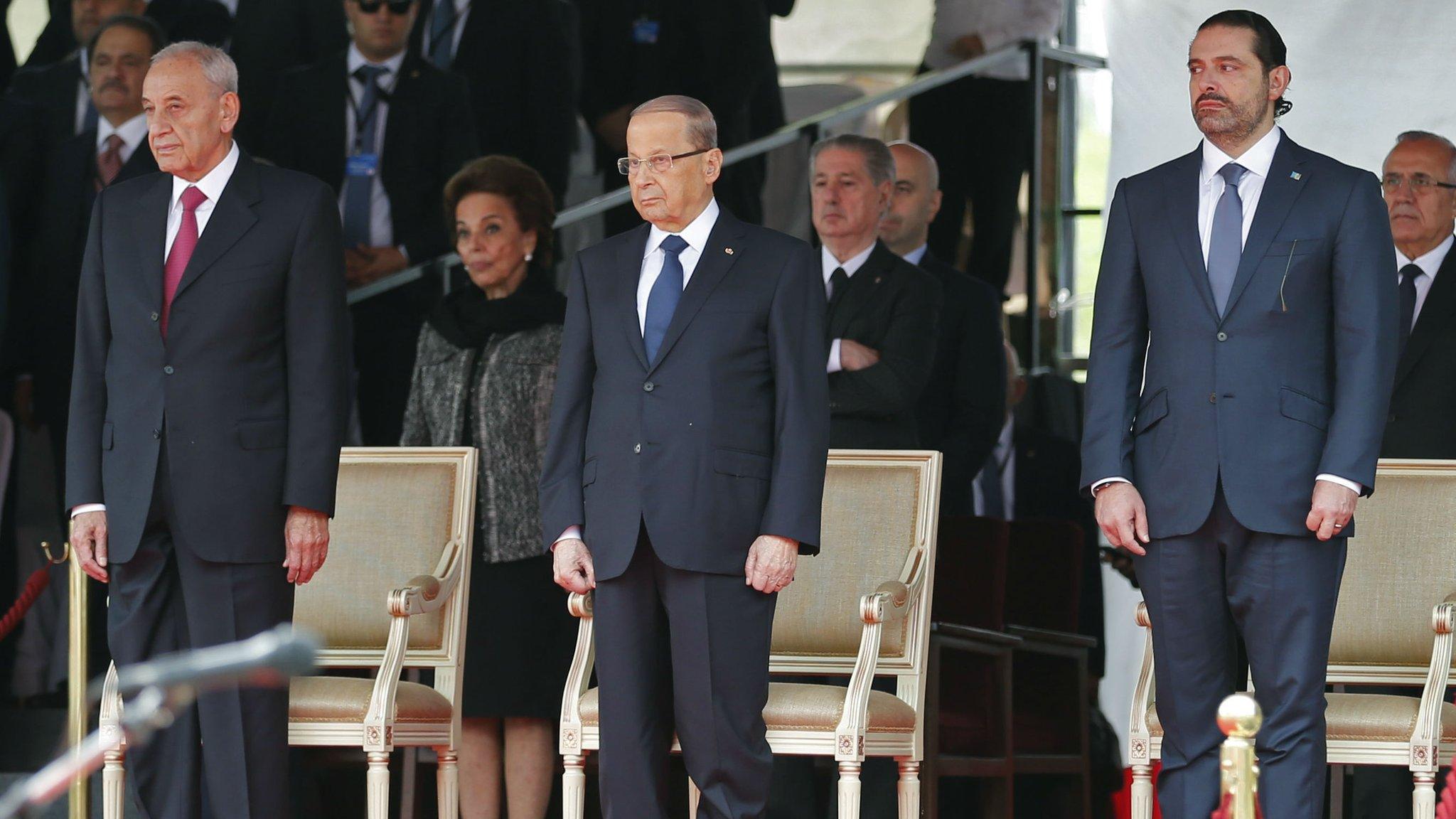

The protests cut across sectarian lines and involved people from all sections of society

Ostensibly, the massive protests were triggered when the government - desperate to raise revenues - proposed a tax on voice calls via messaging services such as WhatsApp.

But the reality is that the demonstrations were a revolt against a corrupt political elite, which has provided almost no public services.

Mahdi's memories of the joy of protests have been tempered by Lebanon's rapidly deteriorating situation.

Banks in Tripoli were attacked when growing economic hardship triggered unrest in April

"We need be taking to the streets now more than ever before," he says. "The situation a year ago was easier than it is at the moment."

Short of war, it's hard to imagine a more horrific year for Lebanon.

The country is in economic collapse after the nation's banks ran what effectively amounted to a Ponzi scheme.

The Beirut port explosion was caused by the detonation of ammonium nitrate stored unsafely

It was followed by the coronavirus pandemic and then, this summer, the devastating blast at Beirut's port, which exposed the corrupt and incompetent core of the Lebanese state.

The explosion on 4 August was caused by the detonation of approximately 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, which had been, inexplicably, stored at the port for years - with the full knowledge of the authorities.

The blast killed almost 200 people and injured more than 6,000 others.

Lebanon's political elite has so far resisted most of the protesters' demands

Despite repeated demands from French President Emmanuel Macron for Lebanon's leaders to reform the system, it has been largely business as usual for the country's political class.

Lebanese politics are built on an agreement that ended the country's civil war in 1990 but entrenched sectarianism and a system of patronage.

Just to underscore the hallucinatory nature of politics here, former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, who resigned in the face of the protests a year ago, is now being touted as a successor to the man who replaced him and who, following the Beirut blast, also stepped down.

Saad Hariri (R) resigned as prime minister in response to the protests. He may now return

Lebanon is also increasingly caught in the regional struggle between America and Iran.

The Iran-backed militant group Hezbollah is Lebanon's most powerful political and military organisation.

Last month, the US imposed sanctions on two former Lebanese government ministers for allegedly providing material support to the group.

Lina Boubes says young Lebanese have nothing to lose and will not stay silent

But, paradoxically, because the situation is so bad, some protestors like Lina Boubes argue that it is actually a cause of hope.

"You have to begin somewhere - don't forget it's 30 years of corruption that we're dealing with," says the 60-year-old, who is normally found on the frontline of any protest.

"All our politicians are corrupt, so you have to work from the bottom."

"This generation, they have nothing to lose. From now on, they won't stay silent. They are not going to shut up like they did before."

But others do not share Lina's infectious sense of optimism. The euphoria of the protests last year has given way to a deeper, darker sense of despair.

Many Lebanese with the option to do so are leaving the country. The growing fear here is that without international support, Lebanon is fast becoming a failed state.

- Published13 October 2020

- Published5 October 2020

- Published11 September 2020

- Published5 August 2020

- Published12 June 2020

- Published27 May 2020

- Published13 May 2020

- Published4 May 2020

- Published5 March 2020

- Published13 December 2019

- Published7 November 2019

- Published25 October 2019