Obama's presence 'reassures Asia allies'

- Published

The first objective of President Barack Obama's four-nation trip to Asia has already been accomplished - literally his arrival in Japan.

After previous postponements for multiple domestic crises, including last autumn's government shutdown, Mr Obama's return to the region is itself reassuring, a personal manifestation of the foreign policy "pivot" to Asia the administration enunciated two years ago but has struggled to translate in concrete terms.

Now that Mr Obama is back in the region - his fifth visit as president - what challenges will he confront, what does he hope to accomplish and what does the region want to hear from him?

He arrives in a region that is distracted, concerned and uncertain.

Two countries he will visit, South Korea and Malaysia, are preoccupied with significant tragedies. The recent sinking of a Korean ferry claimed as many as 300 lives, the majority of them high school students. Malaysia is consumed with the ongoing multinational search for the wreckage of Malaysia Flight 370 and the 239 passengers and crew aboard.

The Malaysian government has been subject to significant regional criticism for its confused handling of the disappearance and search. It will undoubtedly welcome the opportunity to change the subject, if briefly. Mr Obama's visit is the first by an American president in almost 50 years.

Another country on Mr Obama's itinerary is the Philippines, still recovering from November's Typhoon Haiyan that killed more than 6,000 people and left four million displaced. Greater regional co-operation on disaster response and humanitarian relief will be on the agenda.

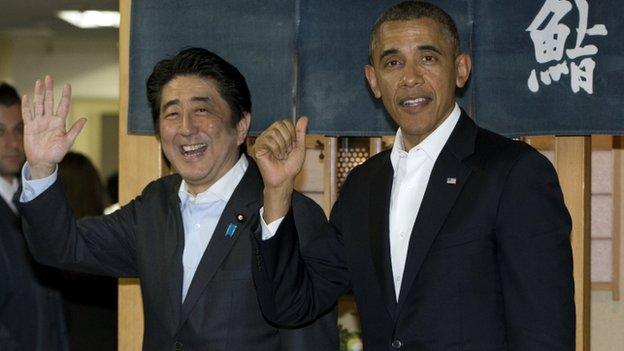

Japan and Korea, key American regional allies, continue to squabble over politically charged statements and actions that have much more to do with the past than the present. The president arranged a trilateral meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye last month on the margins of the nuclear summit in the Netherlands to try to restart high-level dialogue and refocus attention on current challenges such as North Korea.

Ironically, North Korea frequently takes provocative actions during such trips in an effort to steal some attention. Mr Obama will spend some time in Tokyo reviewing Japanese plans to broaden its defence role in the region, and in Seoul discussing revised US-South Korea security arrangements. Any antics from Pyongyang will be a useful reminder of why the US presence in the region matters.

Mr Obama's trip does not include a visit to China, but Beijing will be in the background throughout and will be listening attentively to what the president says at each stop.

With the Philippines still rebuilding after the autumn's Typhoon Haiyan, regional humanitarian co-operation is likely to be on the agenda in Manila

The region has welcomed renewed American engagement to balance an assertive China. Each country he visits has some kind of territorial dispute with China and will be looking for assurances the US will be there if push ever comes to shove. The US and the Philippines will announce enhanced defence co-operation during his stop in Manila, including the regular rotation of US forces back to Philippine bases.

Mr Obama faces a delicate balancing act, reasserting America's commitment to the region and the importance of its security relationships without feeding China's concerns that Washington's actual policy is not engagement but containment.

While the president is in Asia, he will keep an eye on the ongoing crisis in Ukraine. America's allies are as well, trying to judge what it means to Washington's global commitments. Mr Obama will have his own questions, such as whether Japan and others are prepared to impose meaningful economic sanctions against Russia if it moves aggressively into eastern Ukraine.

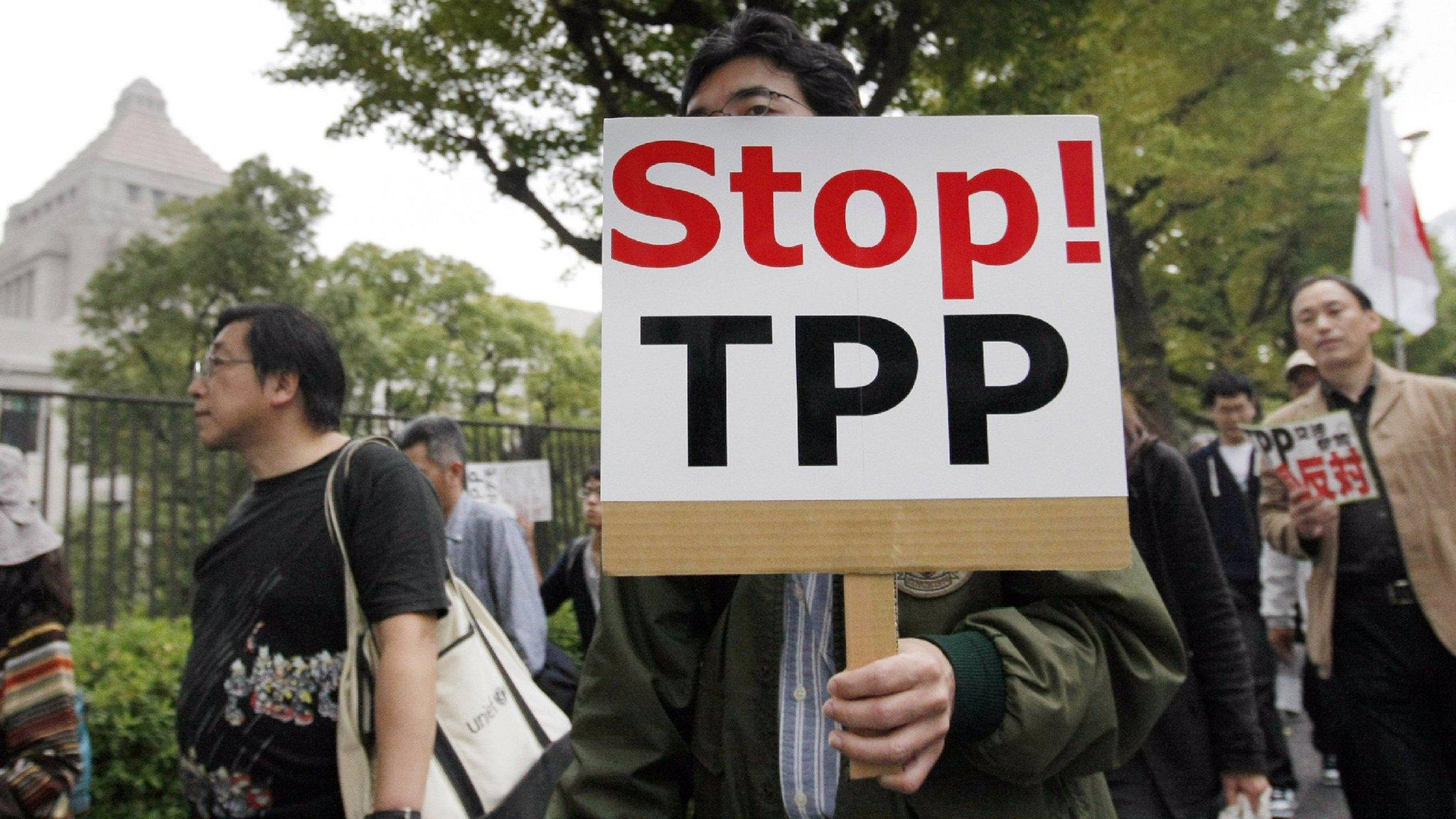

Beyond security, trade will also be on the agenda. Japan and Malaysia are engaged in negotiations regarding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP). South Korea and the Philippines are waiting in the wings. Mr Obama's ability to announce some progress with Tokyo on outstanding market access issues related to Japanese agricultural products and American automobiles will be a strong signal that there are mutually beneficial policies behind the American pivot.

PJ Crowley is a former assistant secretary of state under President Barack Obama and is now a professor of practice and fellow at The George Washington University Institute of Public Diplomacy and Global Communication

- Published23 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published24 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published23 April 2014

- Published13 February 2014

- Published10 November 2014

- Published25 March 2014