US race riots: Five ways to rebuild trust

- Published

The relationship between black Americans and the police is once again in the spotlight.

This time, Charlotte in North Carolina is a focal point of unrest, after a black man was killed by officers this week. There have also been peaceful protests in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where a police officer has been charged with manslaughter.

This is a recurring cycle of violence in the US. According to one research group, over 100 unarmed black people, external were killed by the police in 2015 and a string riots have occurred following similar shootings in 2016.

But what can be done to resolve this?

Five US experts share their thoughts on rebuilding trust between black American communities and the police.

More police in the community - Christopher Bracey

Like any social problem, the first step is to simply acknowledge that a policing problem exists. I think one of the difficulties Americans are facing right now is that there is some disagreement as to whether there is a problem at all.

One practical thing that needs to be done immediately is to push towards more community policing. It really changes the dynamic, the cultural dynamic, because officers are members of the communities they operate in.

If a citizen shops at the same grocery store as his local police officer, they will recognise each other as human.

I think a lot of the problems we see have to do with geography. You have to put people in the same geographical spaces, to occupy the same spaces.

When you do, people see each other and interact with each other, not necessarily in the structured work environment, but in the unstructured social environment. That's why I think community policing works.

Christopher Bracey is an expert on US race relations, individual rights and criminal procedure. He is professor of law at Georgetown University in Washington DC.

A memorial service for the five police officers shot in Dallas

Housing and education key - Robert J Sampson

There's always a tendency to say let's train the police and they're not going to be prejudiced and the problem will go away. Well, no.

That's obviously important and needs to be done. But clearly, as we've seen in some of the shootings, even the officers have been black.

I think the patterns of tension we are seeing now are rooted in long-term inequality and disadvantage.

Violence has, for a long time, been concentrated in poor communities, especially segregated communities and minority communities that have been subject to disinvestment on the part of the state.

So in some sense, when you look at it scientifically, it's not really a surprise when you see occurrences of conflict between these people and the police.

Criminal justice, housing and education reform really need to be coupled to address this issue. That is the message I see from the data.

Robert J Sampson is director of the Boston Area Research Initiative and professor of social sciences at Harvard University.

US police shooting statistics

Over 35% of unarmed people killed by police in 2015 were black in the US, despite only making up 13% of the population

Unarmed black people were five times as likely to be killed as unarmed whites

Police officers themselves were also victims of shootings, with 42 killed in America in 2015

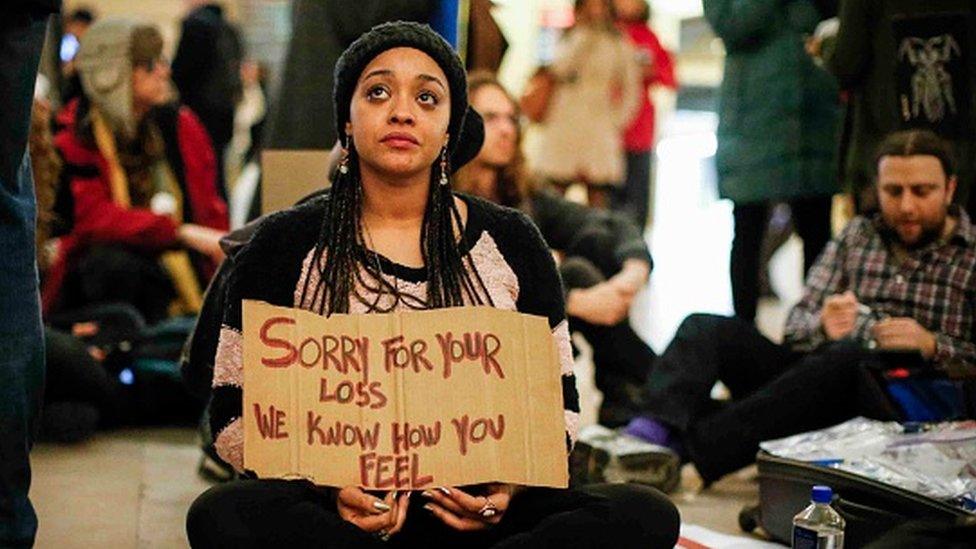

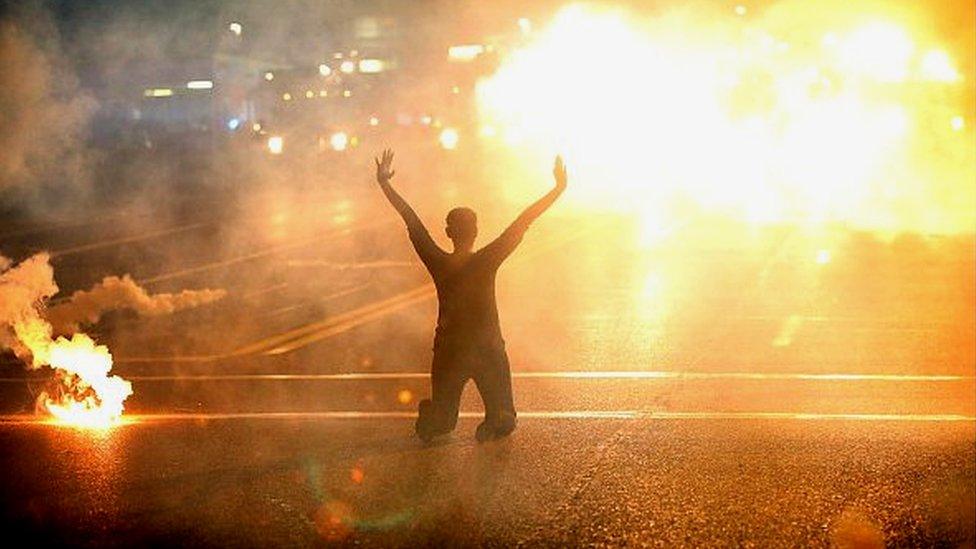

Protests in Ferguson and Baltimore in 2014 and 2015 were just the beginning

Analyse mistakes - Jeffrey A Fagan

Courts routinely award damages totalling hundreds of millions of dollars to citizens who have suffered injuries or rights violations from the police. Taxpayers pay most of those costs.

But as the bills pile up, there is no sign that police acknowledge, analyse or learned from their costly mistakes.

In other public service domains - transportation, medicine, child welfare - there are routines for studying what went wrong: warning signs that were missed, lapses in communication, procedures that can be reshaped to prevent future failure.

Why not in law enforcement? Why is there not a collaborative social autopsy of these cases?

Decades of lower crime rates and the racial breach in public confidence in the police present new opportunities to fundamentally rethink the policing model and the profession.

Jeffrey Fagan is an expert in police accountability and a Professor of Law at Columbia University in New York City.

Find out more

Critics feel the US police do not do enough to avoid use of deadly force

Look at English police - Sam Sinyangwe

It will take a range of solutions to really address this issue. Policy is a huge part of it and will have a huge impact on police violence.

But ultimately it will also take cultural change to address some of the beliefs and prejudices that allow these deaths to happen and allow the system to not do anything about it.

We need to shift the perception in America that black people are inherently criminal or that black people are inherently deserving of a punitive approach by the state.

We also need to have a broader conversation about what is reasonable force [when making arrests].

You know, in England, you have instances of people armed with knives, or in some cases armed with guns, who are not being killed by police. The police are de-escalating these situations without resulting in deadly force.

That seems to be the expectation. That expectation is currently not the norm in the United States.

It seems to be the norm of the culture here that if someone has a knife, a gun or even a toy gun that it is totally legitimate to kill them. I think that is something that needs to change.

Sam Sinyangwe is a data scientist and activist who founded Mapping Police Violence, external, which compiles records of police shootings in the United States.

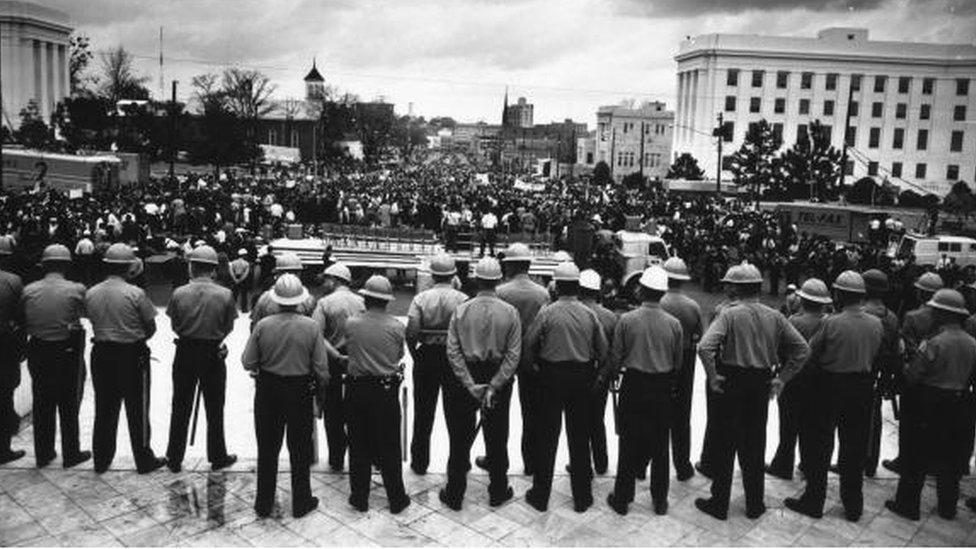

It is almost five decades since the race riots of the 1960s, but racial tensions remain high in some US cities

Reconceptualise policing - Tracey Meares

I think the most important thing we need to do, honestly, is to fundamentally reconceptualise what we think the job [of an officer] is about.

For the last three decades, we have thought about the police as an institution focused on public safety and crime reduction.

But that's not all they do. They do a lot of things that are nothing to do with that actually that involve helping citizens and engaging in positive ways,

We need agencies to focus on these things.

If the police are still understanding their primary role as crime reduction, then we are not going to solve this problem.

Tracey Meares served on President Obama's 2014 Policing Task Force. She is the Walton Hale Hamilton Professor of Law at Yale Law School