Flint water scandal: More state officials charged

- Published

Eight Michigan state employees and one city worker have been charged thus far in the scandal

Six Michigan state workers have been charged with hiding data that showed that drinking water was unsafe in the city of Flint.

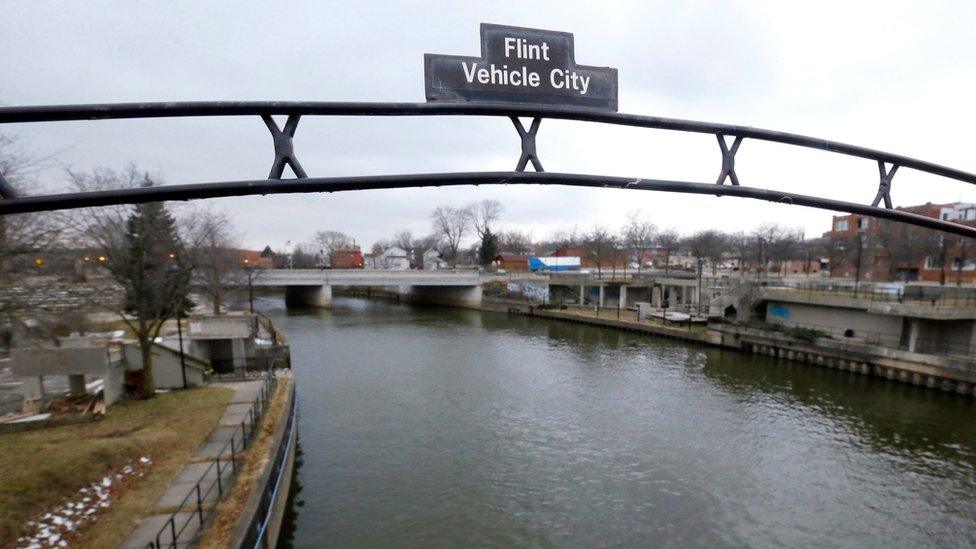

Flint's drinking water became contaminated with lead in 2014 after the city changed its water supply.

The lead investigator said that they "effectively buried" data showing that elevated levels of lead in children's' blood was tied to the water supply.

The six people are all health and environmental workers.

Investigators said they put "children in the cross-hairs of drinking poison".

The majority African-American city changed the source of its water supply to the Flint River after previously receiving it from Detroit, to save money.

Although the water has improved, many Flint residents still use bottled water for drinking

The city of Flint says it will cost more than a billion dollars to repair the water system

The acidic water of Flint River corroded the city's pipes, which leached lead into the water.

Several of the charges can lead to time in prison, including wilful neglect of duty, misconduct in office, and conspiracy.

As well as concealing data that "could have saved children" from lead poisoning, employees also manipulated test results, investigators said on Friday.

Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette was asked what motivated these employees to allegedly conceal and falsify data.

Mr Schuette said that he believed those accused "viewed the people in Flint as expendable, as if they didn't matter".

Liane Shekter Smith, Adam Rosenthal and Patrick Cook were employees for the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality; and Nancy Peeler, Corinne Miller and Robert Scott worked for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

A lawyer for Mrs Shekter Smith said that the charges came as a surprise, saying that investigators will be "really hard-pressed to find that she did anything wrong, and certainly nothing criminally wrong".

These are the second batch of charges to be announced after two state regulators and a city employee were charged with official misconduct in April.

Investigators alleged that they engaged in evidence-tampering and other criminal offenses.

Federal regulators say that filtered tap water is now safe to drink, but they still recommend bottled water for young children and pregnant women.

Estimate vary, but experts believe that the repairs could cost over $1bn (£750m).

- Published22 January 2016

- Published4 May 2016

- Published20 April 2016