Canada 150: What does it mean to be Canadian today?

- Published

This week will see many full-throated renditions of "O Canada!"

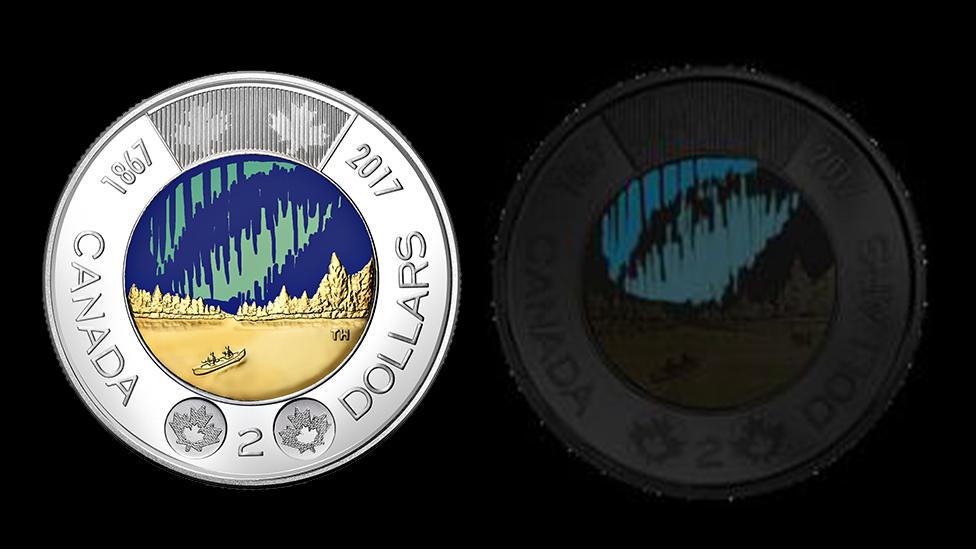

The "Happy Canada Day" signs are already planted in front yards and the country is preparing to celebrate a birthday on Saturday, 150 years after British and former French colonies bonded together at confederation to form the Dominion of Canada.

Hanging over the ceremonies is the question of identity - the great driver of so much of today's politics.

Canada, like other countries, poses the question of who we are and how we define ourselves in a churning global world.

Some say it is insecurity, the changing face of communities, which has been a recruiter for so much of the recent anti-establishment politics and that the call to take back control of countries and borders reflects a broader unease.

Fault line

The Canadian anniversary is gathering attention because Canada is increasingly saluted by some as a champion of liberal democracy.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau won a landslide victory in 2015's general election

The Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has become a standard bearer for internationalism in stark contrast to the economic nationalism of Donald Trump.

Canada finds itself astride one of the great fault lines of modern politics.

Canadians are immensely proud of what has been carved out of wilderness and a harsh climate, but they wear their identity lightly.

When asked "What defines a Canadian?", they often answer with symbols: ice hockey, Tim Hortons coffee, wilderness, a canoe and portage, an array of singers - but the list usually comes with an ironic smile.

Canadians often define themselves by what they are not: their neighbour to the south.

Tim Hortons says eight out of 10 cups of coffee sold in Canada are served at its outlets

There is an appetite for a more positively defined Canadian identity, but for most of the time, many Canadians seem happy for it to remain largely undefined.

Mr Trudeau has offered his own take on what Canada is and how it is defined.

"This is something," he said, "we are able to do in this country, because we define a Canadian not by a skin colour or a language or a religion or a background, but by a set of values, aspirations, hopes and dreams that not just Canadians but people and the world share."

Difficult past

Canada is perhaps one of the few countries in the world where welcoming refugees is regarded as patriotic.

But as the anniversary approaches, the past intrudes.

The lead singer of The Tragically Hip, often referred to as "Canada's band", has spoken of a country incomplete.

Tragically Hip singer Gord Downie was awarded the Order of Canada for his work with the country's indigenous people

Gord Downie asked: "What is it about this country that is not a country?"

Canada, in his view, could not be a country until it had reconciled itself to the First Nations, the indigenous people.

As we celebrate doughnuts and ice hockey, he said, we are not actually a nation, we're a country that hasn't embraced its history.

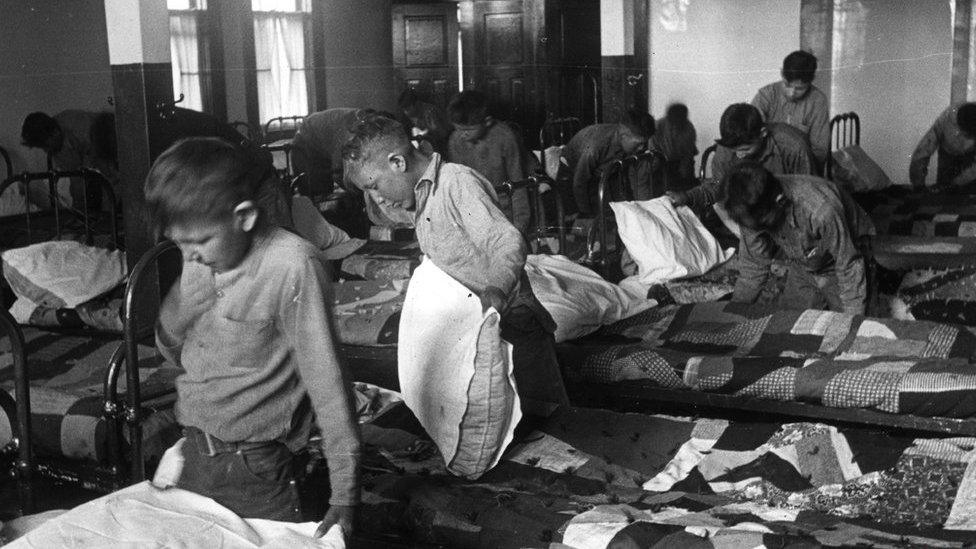

The scars of the recent past still wound: the 150,000 Inuit and Metis children who were removed from their communities between 1840 and 1996, and sent to residential schools in order to assimilate them.

Indigenous children at a residential school in 1950

Some of the First Nations want to be part of modern Canada, but many grieve for land and culture that they believe was stolen from them.

In recent years Canada has undergone immense change. Toronto is now one of the most multicultural cities in the world, although economic power still largely rests with older Canadian families.

"It feels like stomping on the graves of my ancestors"

The British connection

For much of the time, the world ignores this country and the immensity of its wilderness.

I emigrated to Canada in the 1980s. What I saw then - and it remains true - is that for many people in the world the flag is a symbol of tolerance, of refuge, and of a civilised country.

As the country looks to the future, there is the issue of the British connection and the role of head of state. On the prairies of Saskatchewan or in the increasingly diverse city of Vancouver, Britain seems far away, a distant relative.

There is speculation as to what will happen when Prince Charles inherits the throne. Will Canada welcome him as its head of state?

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge went on a royal tour of Canada in 2016, five years after they first visited the country as newly-weds.

The younger Royals have been attentive to Canada, but polls suggest Canadians will eventually vote for change.

However, changing the head of state does not seem to be an immediate priority. Indeed, many Canadians are wary of opening up the issue of identity.

Defining how a Canadian head of state was chosen or elected would be hugely sensitive, not least to the French-speaking Quebecois, who held two referendums on independence in 1980 and 1995. The majority for staying in Canada in the latter vote was wafer-thin.

Less predictable friends?

Canada has fostered its alliances - most often as a junior partner - but its closest allies have become less predictable friends.

Britain is seen by some Canadians as preoccupied with its own identity crisis, bruised by the fallout from the Brexit vote and inward looking. Similarly some consider America to be undermining the very institutions it helped create to shape international order, such as Nato.

Germany and Canada are both recalibrating their relationships with the US and the UK

Canada, like Europe, is dropping broad hints that - as the German Chancellor Angela Merkel put it - "the times in which we could rely on others - they are somewhat over".

Recently, Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland gave what for a Canadian is an unusual assessment of where the country finds itself with regards to the United States.

"The fact that our friend and ally," she said, "has come to question the very worth of its mantle of global leadership, puts into sharp focus the need for the rest of us to set our own clear and sovereign course."

The Canada of the future may prove to have a more distinctive and assertive voice.

As Canada celebrates its 150th anniversary, BBC World News will explore this vast country throughout July - from discovering some of the most remote places in Canada on The Travel Show to documentary-style programming in Canada Stories.

To mark this occasion, we are offering Canadian audiences the chance to watch BBC World News as a free channel preview. More details here.

- Published28 June 2017

- Published19 June 2017

- Published7 June 2017

- Published30 May 2017

- Published25 May 2017

- Published8 January

- Published25 September 2016