Joe Biden: Can Obama's vice-president stay the Democratic frontrunner?

- Published

A look back at Joe Biden's life and political career

It's been four weeks since Joe Biden announced he was running for president. Since then, in defiance of what was conventional wisdom, he's risen in the polls, posted impressive fund-raising numbers and seemingly shrugged off allegations of inappropriate physical contact with women.

The candidate many thought to be a paper tiger, temporarily buoyed by high name recognition and little else, has shown some teeth.

There are plenty of potential pitfalls ahead, however, and numerous ways to stumble before the finish line. As is frequently said, a presidential campaign is a marathon, not a sprint. Does the 76-year-old veteran politician from Delaware have the legs to turn his early lead into his party's nomination - and, in 18 months, a presidential victory?

Why Biden is the frontrunner

On a sunny Saturday afternoon, Joe Biden "officially" kicked off his presidential campaign in front of roughly 6,000 supporters in Philadelphia.

While the attendance fell far short of the opening campaign rallies of Senators Kamala Harris of California (20,000) and Bernie Sanders of Vermont (13,000), it at least temporarily answered the question of whether real people exist who are, in fact, actually enthusiastic about Biden's candidacy.

"I think he's exactly what everybody is waiting for," says Jason Pudleiner, a Philadelphia public defender who stood in a long line for a Biden t-shirt after the Philadelphia rally. "It's the perfect combination of spreading hope, but also somebody who is not going to get bullied by Donald Trump. I love this man."

Testimonials aside, the on-the-paper case for Joe Biden as a durable front-runner is straightforward. He sits atop the latest RealClear Politics aggregation, external of national Democratic preference polls with 38%, well ahead of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders at 19%.

His lead narrows in early voting states of Iowa and New Hampshire, but is formidable in South Carolina thanks to strong support from black voters.

According to an analysis, external by Geoffrey Skelley of the political forecasting site FiveThirtyEight.com, a well-known candidate like Biden who is polling nationally in the high 30s or better has won his party's nomination 75% of the time since 1972.

Then there's Biden's rapidly expanding campaign war chest.

While he had a later start than the other big names in the field, in his first 24 hours he brought in $6.3m (£4.9m), topping the grass-roots-driven marks of Sanders and former Texas Congressman Beto O'Rourke. He netted $700,000 in one high-rolling fundraiser in Hollywood and is likely to match that mark during an upcoming trip to New York City.

Biden has shown a willingness to rub elbows with the party's well-heeled contributors and donation-bundlers, which may raise the ire of progressives in the party but will provide plenty of fuel for the machinery of his campaign.

Biden also has history on his side. Former or current vice-presidents seeking their party's nomination tend to win - including Al Gore in 2000, George HW Bush in 1988, Walter Mondale in 1984, Hubert Humphrey in 1968, and Richard Nixon in 1960 and 1968.

President Barack Obama presented the Medal of Freedom to Vice-President Joe Biden

Only two former vice-presidents were unsuccessful in their presidential nomination campaigns since 1960 - Humphrey in 1972 and Dan Quayle in 2000.

Occupants of the number-two spot have the benefit of already serving on at least one winning national general-election campaign.

They have the ability to build a national network of donors and supporters through the power of their office. And they're usually a known political quantity, which counts for a lot.

Why Biden might prevail

According to a Quinnipiac poll, external of voters, Biden is both well-known and well-liked - the strongest candidate in the field by that metric.

Forty-nine percent of Americans said they had a positive view of the former vice-president, while only 39% were negative on him. Both Sanders and Trump, who have similar levels of name recognition, were underwater.

South Carolina State Senator Dick Harpootlian, former chair of the state's Democratic Party and a long-time Biden supporter, says the key to the former vice-president's appeal is his personal attributes.

"He's probably the most genuine, honest and sincere person I've met in politics ever," he says. "A lot of folks you deal with are calculating, everything they say is more worried about re-election than getting the job done. I think Joe Biden is genuinely good."

Biden garnered considerable goodwill in 2015 following the death of his 46-year-old son Beau to brain cancer.

Personal tragedies have marked Biden's adult life, as he also lost his first wife and daughter in an automobile accident in 1972, shortly before he was sworn in as one of Delaware's two US senators.

Senator-elect Joseph Biden and wife Neilia cut his 30th birthday cake at a party in Wilmington, 20 November while his son, Hunter, waits for the first piece.

"I think the tragedies he's been through and how he gets through them demonstrates that he's a person of tremendous character, strength and faith," Harpootlian says.

Biden also benefits from his eight-year association with Barack Obama, the man who bested him in the 2008 Democratic primary contest, then selected him as his vice-presidential running mate.

It's probably one of the principal reasons Biden's support among black voters is so high, even with candidates like Senators Kamala Harris and Cory Booker running against him.

His two terms in the second spot, where he frequently appeared at the president's side or just over his shoulder, has allowed Biden to lay claim to much of Obama's legacy - including passage of the Affordable Care Act, the economic stimulus package and financial industry reform.

During his Philadelphia speech, Biden cited both the 2009 stimulus package and Obamacare as reflecting how he would govern - co-operating with Republicans on the former, while going it alone with Democrats in the latter.

"I know there are times when only a bare-knuckle fight will do," Biden said. "But it doesn't have to be that way on every issue."

'Beat Trump'

There was a moment about midway through Biden's Philadelphia kick-off rally that perhaps illustrated the greatest strength - and potential peril - of his nascent presidential bid.

The benediction had been delivered, the Pledge of Allegiance recited, and the National Anthem sung. A gospel choir had belted out Amazing Grace and the 1971 Marvin Gaye hit What's Going On. Aides were fiddling with the Tele-prompter stands on the podium, to ensure the candidate looked just right before the made-for-television backdrop of Philadelphia's skyline on a radiantly sunny afternoon.

After the crowd offered a few short-lived chants of "We Want Joe!", a woman took a different tack.

"Who don't we want?" she began shouting. "Trump!" Others joined in. The enthusiasm was obvious, but from a distance it sounded like they were just chanting the president's name.

Plenty of candidates for the Democratic nomination are running on who they are or what they can do. Elizabeth Warren has her stack of policy proposals. Sanders preaches political revolution. Pete Buttigieg and Booker tout their personal attributes and sunny disposition.

Biden has made the early days of his campaign about who he's not - Donald Trump. And what he can prevent - Trump's second four-year term in office.

More from Anthony on the candidates

"I think many of these other candidates have great ideas," Harpootlian, who recently hosted a fundraiser in South Carolina for Biden, says. "They have great aspirations and they're good on the stump - all the things you want in a candidate. But they don't have the experience, the gravitas or the toughness that Joe Biden brings to the fight with Donald Trump. He can go toe-to-toe with him in any debate, anytime, anywhere."

During his Saturday speech, Biden ticked through a laundry list of Democratic policy priorities on healthcare, education and the environment, but he concluded that "the single most important thing we have to do to accomplish these things is defeat Donald Trump."

"If you want to know what the first and most important plank in my climate change proposal for America is," he said. "Beat Trump."

It's a message that has resonated with the crowd in Philadelphia and a Democratic primary electorate that tells pollsters that selecting a nominee who can win is their top priority in 2020.

"Trump has got to go," says David Dignetti, a plumber from Philadelphia who came to the Biden rally with his wife Deirdre. "I just want government to work again. It's got to go back to the way it was."

"Make America great again, again," echoes Dierdre. "It was great under Obama."

David Dignetti and his wife, Dierdre, at Biden's Philadelphia rally

Why Biden might falter

There is a danger, of course, in basing a candidacy on the appearance of electability. If something were to happen to strip that veneer of appeal - a lack of sharpness in the debates, a stretch where the candidate lacks the requisite energy or enthusiasm - there's not much left to fall back on.

Biden can get things done? There are candidates who have more detailed or ambitious plans. He's a nice guy? He's not the only one. And you know what they say about nice guys.

Back in March, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, a rising star in the party's progressive wing, made an explicit argument against choosing a nominee based on perceived electability.

"I think that in this first initial stage, we have a responsibility to find and really fight for who we believe in," she said. "What people think will win is wrong. Almost always."

Opting for the "electable" candidate, she said, is how voters end up with candidates they don't really like. And while Biden's favourability ratings are currently high, Biden has areas that are ripe for attack.

Questions have already been raised, by Donald Trump and his surrogates, about son Hunter Biden's Ukrainian business interests and anything improper the elder Biden might have done to help advance them.

Then there are the inappropriate touching accusations - complete with uncomfortable video of public affection and testimonials from two women. Biden has responded to the criticism by saying he's an empathetic person, but that he understands expectations and standards have changed.

That defence could always crumble if new evidence or allegations surface.

Biden's age may also be a target. He would be 78 on inauguration day 2021 - by far the oldest president ever elected to a first term in office.

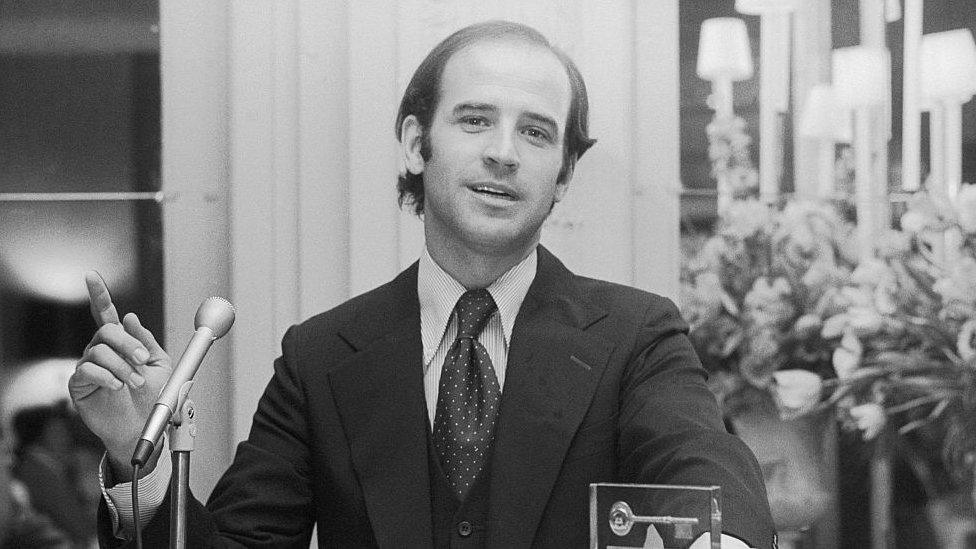

In 1974, Biden was the youngest US senator

According to a Gallup poll earlier this month, external, only 63% of Americans said they would be willing to vote for someone over 70 for president. Of course, Trump himself is 72, so they may not have much of a choice.

"You get a lot of experience with age," says Leeann Held, a retired FBI agent who attended the weekend Biden rally. "I know a lot of great people who are that age."

A full 18 months on the campaign trail can wear even a younger candidate down, however.

And while Biden trotted on stage in Philadelphia sporting aviator sunglasses and a broad smile, if he falters down the stretch it could change the political equation.

With age comes other challenges, as well. Biden held public office for nearly 40 years - long enough for the file photos of his first campaign for Senate from Delaware in 1972 to be grainy black-and-white.

Early in his political career, he sided with southern segregationists in opposing court-ordered school busing to racially integrate public schools.

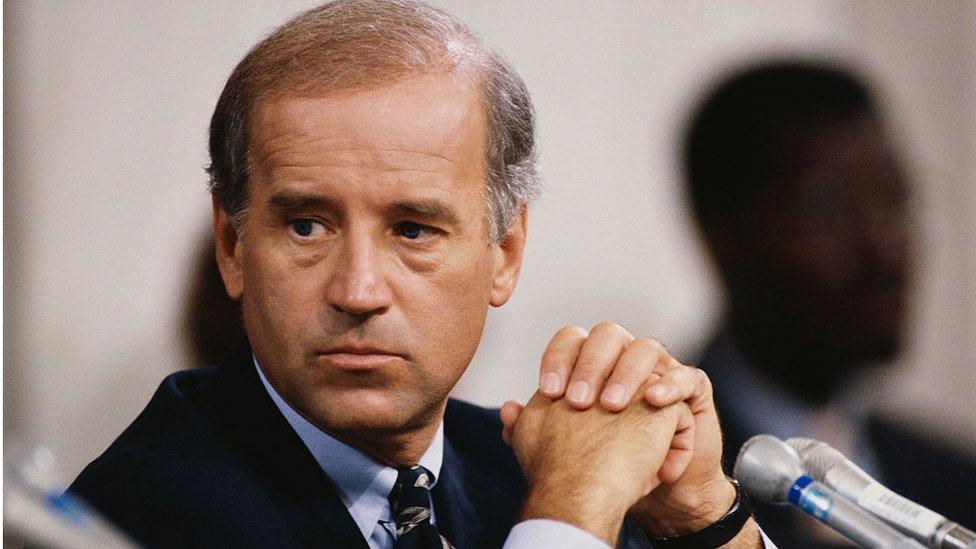

As chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991, he oversaw Clarence Thomas's Supreme Court confirmation hearings and has been sharply criticised for his handling of Anita Hill's allegations that she was sexually harassed by the nominee.

Biden was a fierce advocate of a 1994 anti-crime bill that many on the left now say encouraged lengthy sentences and mass incarceration.

He voted for the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and has frequently pushed for legislation favourable to the large financial institutions based in Delaware, including a 2005 financial bill that greatly curtailed individual bankruptcy rights.

It's the kind of record that, taken as a whole, makes Biden an unlikely standard-bearer for the modern Democratic Party.

Then-Senator Joe Biden during the Clarence Thomas Hearings in 1991

"The gap between his image and his record is really stunning," says Norman Solomon, a syndicated columnist and Bernie Sanders supporter. "I think he thrives on lack of knowledge of what he's been doing for four decades."

During the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Solomon helped stage organised demonstrations by Sanders delegates who were suspicious of Hillary Clinton and the Democratic establishment. He says this time around, they may be even more wary of Biden, who he says is the "default zombie candidate of the old Democratic Party".

"Biden is already very unpopular with progressives," he says. "The gap between the mass media coverage and the online progressive media coverage of Biden is huge. In one, he's almost saint-like. In the other, he's damn near satanic."

The question, then, becomes what Biden's opponents will do to bring the front-runner back to the pack. Elizabeth Warren has gone after the former vice-president for his support of the 2005 bankruptcy bill, citing her anger at it as the reason she first got into politics.

"Joe Biden was on the side of the credit-card companies," she told a reporter last month.

Washington Governor Jay Inslee, announcing another piece of his plan to combat climate last week, said Biden must "up his game" on the environment.

"He's going to have to say that we have to remove our reliance on fossil fuels in the electrical grid," Inslee said. "I have not seen to date any suggestion that he can do that."

Looking ahead to 2020

According to Solomon, however, it will be Sanders who comes at Biden the hardest. Already, the Vermont senator has questioned his opponent's past support of trade deals, including the North American Free Trade Agreement.

"If you look at Joe's record, and you look at my record, I don't think there's much question about who's more progressive," Sanders said in a television interview, external earlier this month.

The rest of the field, Solomon says, may play nice with Biden in hopes of being his running mate or serving in his cabinet.

"As in so many other aspects," he says, "it will fall to Bernie to be the truth-teller."

In other words, get ready for a fight.

Hillary Clinton or Warren G Harding?

The thing about Biden's campaign message is it sounds a lot like Hillary Clinton's pitch to Americans in 2016. Like her, he says he has the experience to get things done. Like her, he's arguing that Mr Trump is temperamentally unsuited for the presidency. Like her, he's making the pitch that calls for togetherness can overcome the politics of division.

In 2016, Clinton's slogans included "Stronger Together" and "Love Trumps Hate". Biden gave his Philadelphia speech in front of video screens emblazoned with the word "unity" and spoke about America being at its best when it's been "one America".

"The nation needs to come together," he said. "And it has to come together."

Biden has drawn fire from critics for saying that the Trump presidency is an aberration, and he returned to that theme on Saturday.

"This is not who we are," he said. "We are better than this.

What the country needs now, he said, is a step back from the divisiveness of the Trump years. (That he is associated with the Obama administration, much of which was characterised by political acrimony and gridlock, seems glossed over.)

In 1920, in the aftermath of World War I, Warren G Harding campaigned on the slogan of "a return to normalcy". Contemporaries mocked the term as ungrammatical, but the appeal of the message was its simplicity.

In one of his most famous lines, he said that America needed healing, not heroics; restoration, not revolution; adjustment, not agitation.

If Democrats in 2020 want revolution or agitation, the former vice-president won't be their guy. He's betting, however, that "normalcy" is what the nation wants - and he can deliver.

"No one likes fighting with their own family, and I find myself fighting with my family and my friends," says Brandi Bogard, a pharmaceuticals company employee who volunteered for Biden at his rally. "I sit in front of the television and cry. I never used to be very political, but I can't help it."

Bogard described Biden as the "loving grandfather" the nation needs.

After four years of the Trump presidency, Mr Biden is staking his presidential hopes on the belief that Americans aren't so much angry as they're exhausted - or, at least, ready for a change.

Who will take on Trump in 2020?

Joe Biden could be the man to keep Donald Trump from being re-elected. But who else has a shot at becoming the next president?

- Published18 March 2019

- Published14 February 2019

- Published22 March 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published1 April 2019

- Published3 April 2019

- Published26 March 2019

- Published5 March 2020

- Published12 March 2019