Trumplomacy: What's the US endgame in Iran?

- Published

An effigy of Mr Trump seen at a May 2019 rally in Tehran

Is the president of the United States bouncing off the walls in different directions from one moment to the next when it comes to Iran?

That is how one Democratic senator, Tammy Duckworth, describes his standard operating procedure. "It's endangering our nation on national security," she tells me.

To be fair, Mr Trump did consult congressional leaders about whether to take retaliatory strikes after Iran shot down that unmanned US drone last week.

He got a lot of input from both sides of the aisle, Republican Congressman Michael McCaul, who was present, told me. Mr McCaul described the White House's strategy as "cohesive".

The president also heard from his generals and his national security advisers in a weighty day of deliberations.

And, according to the New York Times, he heard from one of his favourite TV hosts at Fox News. If Mr Trump got into a war with Iran, Tucker Carlson declared, he could kiss his chances of re-election goodbye.

Was that the deciding voice that convinced the president to call off the strikes at the last minute?

Who knows.

A pro-regime change rally outside the White House in June 2019

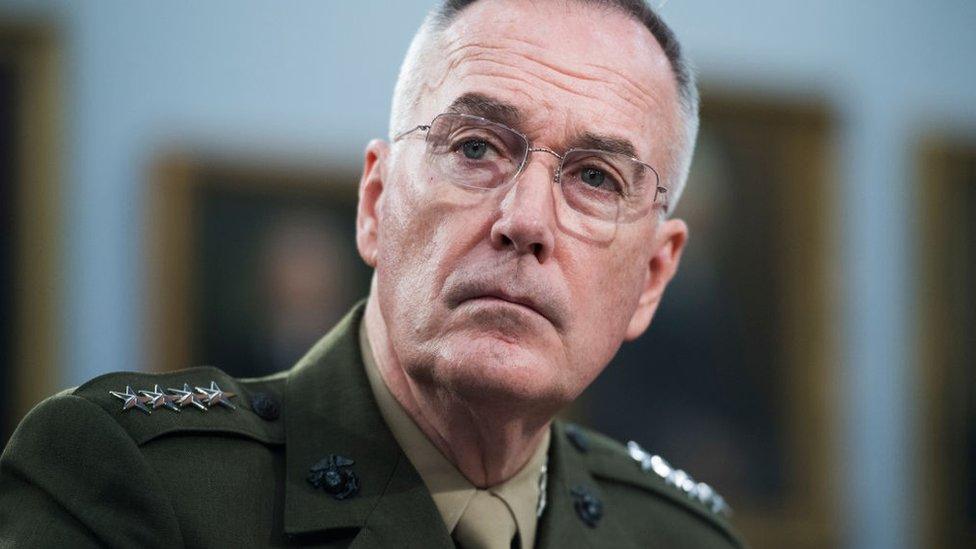

Mr Trump cited his concern about Iranian casualties. His top general Joseph Dunford apparently also had outsized influence, and he counselled caution.

But more than any other national security crisis, this one has exposed the tension between President Trump's desire to look and act tough, and his reluctance to get involved in a foreign war. After all, he promised voters that he wouldn't.

So while he's been celebrating his restraint, even downplaying the threat of Iranian actions, he's also been telegraphing his resolve to use force if necessary: to obliterate Iran if it launches attacks.

In short there has been a certain amount of bouncing.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo says sanctions will force Iran to be a "normal country"

But there's another layer to these mixed signals about Iran policy: Mr Trump's national security adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seem to have a different agenda than he does.

President Trump mostly talks about the Iran nuclear deal, from which he withdrew, about how bad it was because it was too weak, how his predecessor Barak Obama gave away too much in exchange for too little.

He's also regularly announced how eager he is to negotiate a bigger better bargain: Call me, he's said to the Iranians, even passing along his telephone number through an intermediary.

That is not the tone we get at the state department.

General Dunford reportedly urged Trump to be cautious about strikes against Iran

Mr Pompeo does talk about negotiations, but mostly he stresses maximum pressure: the oil and financial sanctions that are crippling Iran's economy.

It's night and day from the previous administration, when our reporting focused on the painstaking process to lift those sanctions by getting Iran to accept limits on its nuclear programme. At first it was news to see then Secretary of State John Kerry in earnest conversation with his Iranian counterpart Javed Zarif, until it became routine.

Mr Pompeo also stresses that the sanctions will remain until Iran meets 12 demands. These include renegotiating its nuclear accord, yes. But also things like scaling back its missile programme and rolling back its influence over regional militias.

Iran's president says the US is lying about wanting dialogue

The secretary of state calls this forcing Iran to change its behaviour, to behave like a "normal country".

At the same time he's admitted that he doesn't believe this regime can change in the way the US is demanding. He's said Iran doesn't have moderate leaders, dismissing the traditional distinction between the hardliners, and the pragmatists who negotiated the nuclear deal.

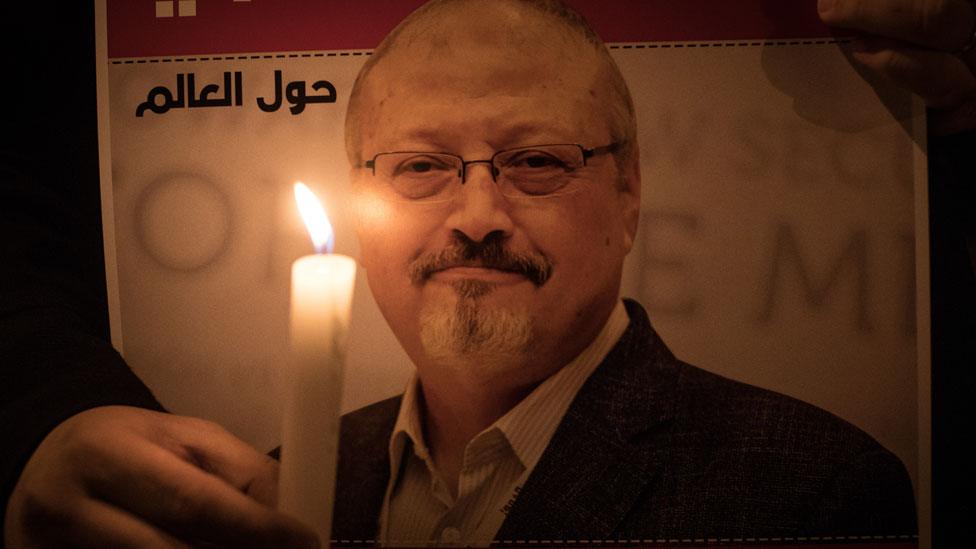

Someone commonly seen as a pragmatist, Mr Zarif, is now set to be sanctioned this week. It's a highly unusual move that escalates tension rather than creating diplomatic space for any talks.

Iran's Foreign Minister Javed Zarif is due to face new US sanctions

America's allies and its lawmakers agree that Iran's behaviour in the region is disruptive and dangerous, and needs to be curbed. But critics say this 12-demand approach would essentially force Iran to transform its entire foreign policy, on issues seen as vital to its national security.

And that's just not going to happen.

One of the administration's goals is to deny Iran the revenue to carry out its "expansionist" foreign policy, Mr Pompeo's Iran envoy, Brian Hook, told a congressional committee last week.

President Trump: "The assets of Ayatollah Khamenei and his office will not be spared"

But what's the end game? A new nuclear deal? Transforming the regime?

That's an urgent question on Capitol Hill, mostly for Democratic lawmakers but not only.

"The administration has a one-track plan, it is maximum pressure. It does not have a strategic plan to get Iran back to the negotiating table," Senator Bob Menendez told BBC News - he's the top Democrat in the Senate dealing with foreign relations.

"If all you do is create pressure and you don't have an escape valve, it blows."

Anti-American protests in Iran in May 2019

There's fear that President Trump could blow things up without seeking authorisation from Congress for any new war, which he's supposed to do.

Mr Hook got a grilling on that.

"Under the constitution, Congress has the power to declare war, yes?" was the question posed again and again by Democratic Congressman Ted Lieu. "And it's not a trick question!" he added.

Mr Hook didn't answer it definitively and neither has Mr Pompeo.

There's the usual amount of political theatre around this issue, but also a sort of "Crazy".

Americans use crazy as a noun: "The Crazy".

"The Crazy in Washington."

Will Mr Trump be able to make "The Crazy" work with Iran?

Trump returns from a Camp David presidential retreat in late June 2019

He likes to keep his adversaries off balance, but he can also change course when he senses opportunity. Remember the "fire and fury" threats that turned into a love affair with North Korea's Kim Jong-un.

But in this case his adversary has its back against the wall, and the message its hearing most loudly from the confusing noise out of Washington is regime change.

This administration has lurched its way through much of its foreign policy, and most of the officials who had a nuanced understanding of the world are gone.

Many in Washington now fear that the man who's often described as an accidental president may stumble into an accidental Middle East war.

Listen to the full radio programme on BBC Sounds:From Our Own Correspondent

- Published22 March 2019

- Published12 April 2019

- Published17 January 2019

- Published6 February 2019