Biden's climate agenda: Is this the beginning of the end for fossil fuels?

- Published

After years of Trump, the new US administration wants to rejoin world efforts to tackle the climate change emergency

Fossil fuels have been the bedrock of US prosperity for more than a century.

The country's economy, security and society depend on them.

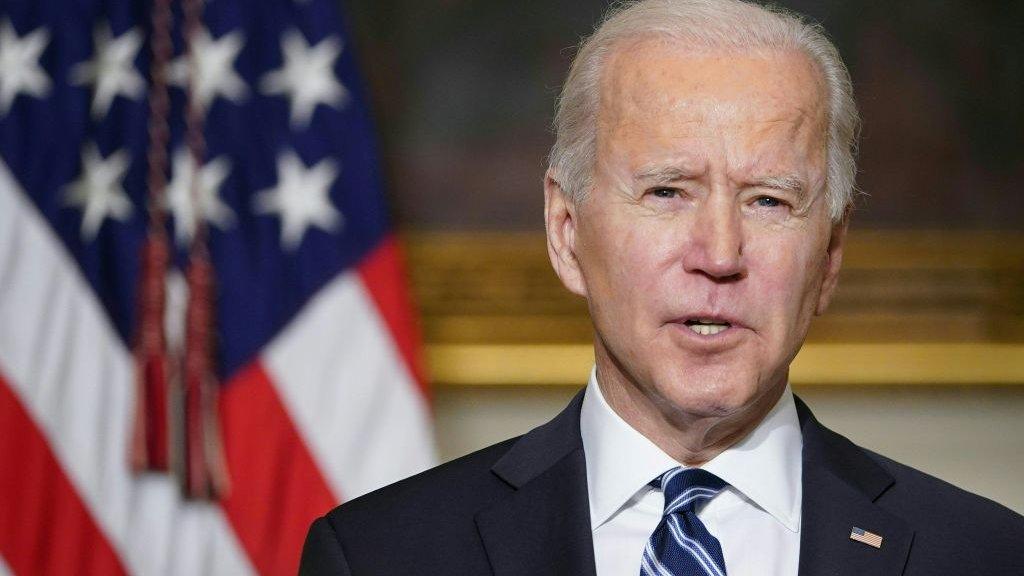

But in the few days since his inauguration, the new American president has gone to war against coal, oil and natural gas with a decisiveness that has caught everyone by surprise.

This week I spoke to the man Joe Biden has tasked with drawing up his climate change battle plans - John Kerry.

"It is one of his top priorities, without any question whatsoever," Mr Kerry assured me. "He'll make more progress on the issue than any previous president."

That seriousness is reflected in his choice of John Kerry as his special envoy on climate.

Mr Kerry was President Barack Obama's secretary of state and a key architect of the Paris climate change summit in 2015.

In other words, he is someone deeply invested in tackling global warming, who understands current global climate diplomacy, and personally knows many of the key people the US will have to work with.

Ambitious start

In the handful of days the new president has been in office, he has already exceeded expectations.

We knew he was going to re-join the Paris climate accord, we didn't know that a few days later he'd order his domestic climate "tzar", Gina McCarthy, to draw up plans to commit the US to "the most aggressive" carbon cut possible.

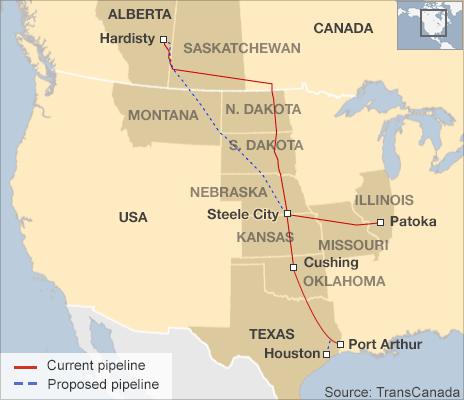

We expected him to try and kill the giant Keystone XL oil pipeline, but not that he'd pull the permit on his first day in office, stopping the 2,000km pipeline project dead in its tracks.

We knew he planned to make climate change a priority in policy-making, but not that he'd order the Pentagon to make it an issue of national security.

It is part of what is being called a "whole government" approach to the issue.

Climate activists on Biden plans: "We're celebrating key victories today"

"He is mobilising every department, every agency of the United States government to focus on climate and he is determined to try and restore America's credibility and reputation," explained Kerry.

Even some of the deepest green activists have been impressed.

"There is a shock-and-awe feel to the barrage of actions," says veteran environmental campaigner Bill McKibben.

The proposed route of the Keystone XL oil pipeline

He believes the flurry of executive orders is designed to make an important point.

The president wants to send "a decisive signal about the end of one epoch and the beginning of another," says Mr McKibben.

That signal is aimed at investors, he says. "Fossil fuel, Biden is making clear, is not a safe bet, or even a good bet, for making real money."

Oil feels the heat

The oil industry has been left reeling. Share prices plunged, and Goldman Sachs warned of a drop in US crude supplies.

"The industry is aghast at these changes," one oil services company CEO told Bloomberg. "They are more direct, more fierce and quicker than what folks expected."

Biden and his team have been meticulous in casting the agenda as an exercise in job creation and economic stimulus in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis.

Mr Kerry repeats the now familiar "build back better" mantra to me.

"If we're going to invest new money," he says, "let's invest it in clean energy, invest it in clean jobs, invest it in those technologies and other things that will build the future, rather than simply being the prisoners of the past."

Meanwhile, there have been a few modest sops to the fossil fuel industry.

Fracking won't stop, for example, although there will be tighter regulations, and Biden promised to put displaced fossil fuel workers to work sealing off the estimated one million leaking oil and gas wells.

The plan to build 1.5 million new energy-efficient homes, and manufacture and install half a million new electric-vehicle charging stations, would also create millions of "prevailing wage" jobs.

And the car industry will be delighted by the commitment to electrify the government's 650,000-strong fleet of vehicles.

But, at the same time, President Biden has reiterated his desire to end all fossil fuel subsidies, ordered a ban on new oil and gas leases on federal land, and said a third of all federal lands must be reserved for conservation.

He also ordered agencies to accelerate the authorising of renewables projects, as part of his effort to double wind capacity by 2030, and make the electricity sector zero-carbon by 2035.

Private sector 'buy-in'?

These initiatives don't depend on the Democrats wafer-thin majority in the Senate, Mr Kerry insisted. These are areas where the president already has authority.

"Now, that's not to say the president isn't going to try and get Congress to be part of this, of course he wants them. But this isn't going to be solely dependent on one source."

For instance, Mr Biden plans to reinstate and strengthen Obama-era regulations, repealed by Trump, on the three largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions: vehicles, power plants and methane leaks from oil and gas wells.

The key, says Mr Kerry, is "a massive shift" in attitudes in the private sector.

Companies are increasingly dealing with climate "upfront and directly", says Mr Kerry.

US car makers are coming to accept that fuel economy standards have to rise, for example.

Only this week General Motors announced plans to phase out petrol and diesel cars and trucks completely, and sell only vehicles with zero emissions by 2035.

And some big oil and gas companies have acknowledged some of the curbs on emissions lifted by President Trump need to be reinstated.

But Mr Kerry knows there will be pushback from others in the fossil fuel industry and from the lawmakers who back it.

Joe Manchin, the Democratic senator for West Virginia, is likely to be a particular thorn in the side of the Biden administration.

He is to lead the Senate Energy Committee and was elected as a defender of his states coal industry.

He famously campaigned with a TV ad that featured him using a hunting rifle to shoot a copy of one of Obama's climate change bills.

And, remember the Senate is split 50-50 with Vice-President Kamala Harris holding the casting vote.

US rejoining world stage 'with humility'

There will be more freedom of action on the international stage.

Indeed, this may be where Joe Biden and John Kerry have their most transformative impact.

Mr Kerry describes the Glasgow climate summit in November this year as "the last best chance the world has to come together to avoid the worst consequences of the climate crisis".

It is a propitious time to be talking.

The cost of renewables has fallen dramatically since he led America's delegation to the Paris talks.

Lots of countries are considering green investments as a way to stimulate their economies post-Covid.

The Los Angeles refinery, California's largest producer of gasoline

And that's consistent with net zero by mid-century pledges that more than 100 countries - including the EU and China - have made recently.

Mr Kerry knows America has to step carefully.

"I think that the fact that the United States has been absent for four years, requires us to approach this with a certain sensitivity and humility."

The hope is, Mr Kerry implies, that aggressive action on the domestic front will give credibility to American efforts to encourage other nations to up their climate ambition.

He said he and the rest of the administration will work hard with the UK government to ensure Glasgow is a success.

"I'm not going to contemplate anything else," he told me, "because it would be a dramatic failure for mankind."

- Published27 January 2021

- Published19 February 2021

- Published27 January 2021

- Published27 January 2021