Scientists have recovered rocks from deep within Earth's mantle

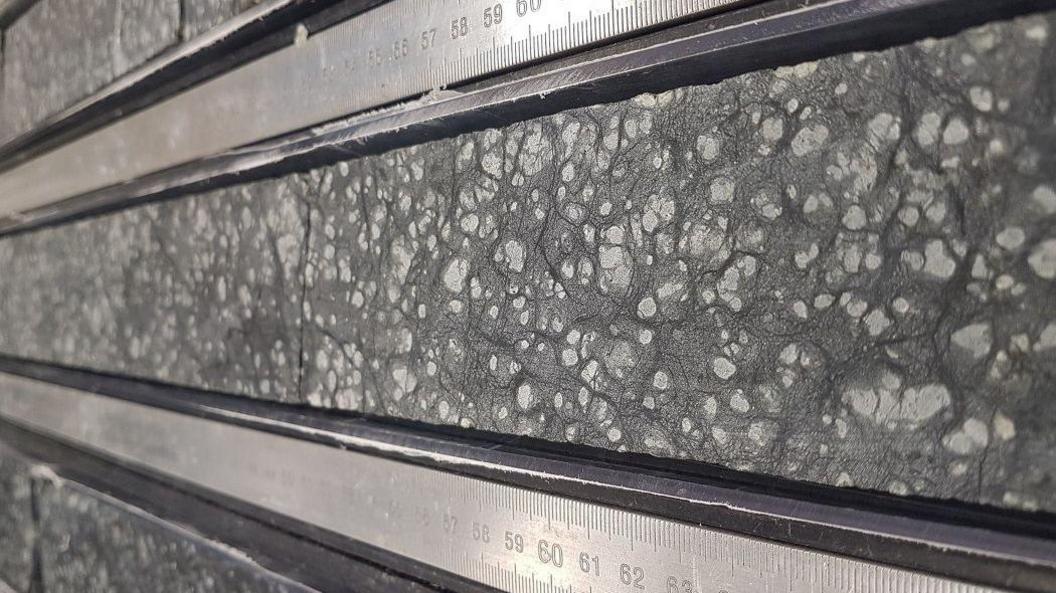

The rock recovered is the longest section extracted by scientists

- Published

Scientists have recovered the first long section of rocks from deep down in the Earth.

The rocks have come from the Earth's mantle, which makes up more than 80% of the planet's volume, and sits between Earth's outer crust and its super hot core.

New research suggests the mantle could reveal some key secrets about the history of the Earth.

Scientists used an ocean drilling vessel to dig the deepest hole ever down into the rock.

The latest stories

Paris 2024: GB's 13th gold medal after kite sailing victory

- Published9 August 2024

Celebrities to face Gladiators in special programme

- Published7 August 2024

Royal Mint turning game consoles and TVs into gold

- Published7 August 2024

Mantle rocks aren't usually accessible, unless they are exposed at locations of the Earth's seafloor where the huge slow moving tectonic plates that make up the planet's surface are found.

One example of this is the Atlantis Massif, which is an underwater mountain where mantle rock is exposed on the seafloor.

Scientists managed to drill a massive 1,268 metres below the Atlantic seafloor, which is more than 1,000 metres more than the previous deepest hole, and extracted a large sample of rock which could offer some big clues about our planet's biggest layer.

The Earth has multiple layers, including the mantle which makes up the majority of its volume

The researchers suggest the rocks they recovered from the mantle are closer to those that were present on early Earth rather than the more common rocks that make up the continents today.

These rocks could help to explain what role the mantle played in the origins of life on Earth.

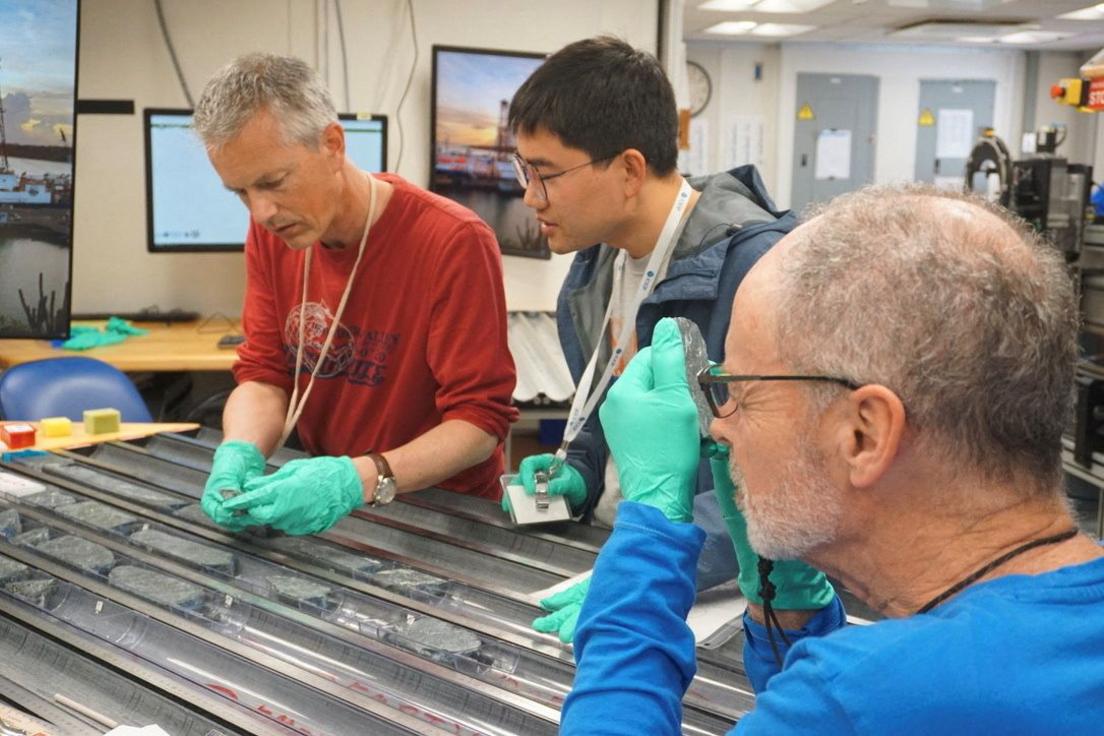

An ocean drilling vessel was used to dig the deep hole over 1,000 metres below the Atlantic seafloor

"When we recovered the rocks last year, it was a major achievement in the history of the Earth sciences, but, more than that, its value is in what the cores of mantle rocks could tell us about the makeup and evolution of our planet," said Professor Johan Lissenberg from Cardiff University's School of Earth and Environmental Sciences who is the lead author on the new study.

"Our study begins to look at the composition of the mantle by documenting the mineralogy of the recovered rocks, as well as their chemical makeup."

A team from Cardiff University are analysing the rock sample to see what secrets about the Earth it may reveal

The rock sample has already revealed some clues about the make up of the Earth which has surprised experts.

"Our results differ from what we expected," Prof Lissenberg explained.

"There is a lot less of the mineral pyroxene in the rocks, and the rocks have got very high concentrations of magnesium, both of which results from much higher amounts of melting than what we would have predicted."

This melting happened as the mantle rose from the deeper parts of the Earth towards the surface.

Further study could provide a greater understanding of how magma is formed and leads to volcanism, the researchers suggest.

More stories on the Earth

- Published7 August 2024

- Published2 November 2023

- Published6 February 2023