Man Utd v Liverpool: A strange kind of sporting love affair?

- Published

It is a supposedly toxic rivalry fired by both history and modern menace: ship canals and industrial struggle; title battles or European charges; managers trading insults and players refusing to shake hands; loathsome chants about death, songs ridiculing tragedy.

All that and more will be raked over before Manchester United and Liverpool meet once again on Sunday afternoon.

Except maybe the truth lies somewhere else. Maybe this is less about hate than a strange kind of sporting love affair. Because both clubs are dependent on each other, and so too - hold down your bile - are their supporters.

"We wouldn't like to admit it, but we do need this fixture. We like this rivalry," says Barney Chilton, editor of United fanzine Red News.

"In the 1980s it was the only fixture we had, really. It was the only one we looked forward to. And although that has changed, we're all still drawn to this fixture in a way that we aren't to others.

"If it wasn't there, we'd really miss it. Leeds? I want them back in the Premier League, but I don't really miss them.

"Liverpool? You don't want them doing well, but you want to be playing them twice a season. What would I rather be watching - Club X on a Tuesday night, or Liverpool this Sunday?"

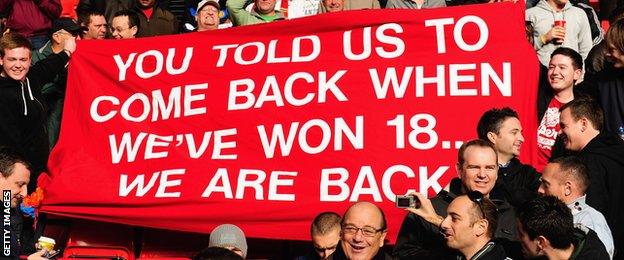

United fans made a banner after winning their 18th league title to match Liverpool's record

Because here is the contrary thing about football rivalries: the supporters who declare their hatred for one another are often so similar that only the colour of their shirt or scarf separates them.

Same sort of home town, same sort of job, same sort of school, same obsession with the same sport.

Fill in a dating profile and they would come up as perfect matches. Stick them at opposite ends of a stadium and it becomes cartoon conflict. Why?

"Fans need rivalries, because they make us feel more important," says Alan Bairner, Professor of Sport and Social Theory at Loughborough University

"It makes people feel good about themselves - that sense of, 'They must fear us', or 'We're better than them'. It's not so much that you get to hate someone else, but that they get to hate you."

"We hate each other because we're the same," says Andy Heaton, from Liverpool podcast and digital magazine The Anfield Wrap., external "We crave United's success, because we had it.

"We are so similar. [Manchester media impresario] Tony Wilson, external came out with a cracker: Manchester might be the heart of the North West, but Liverpool is the lungs.

"When Alex Ferguson talked about knocking Liverpool off their perch - I don't mind that. When they beat us in the FA Cup in 1999, Gary Neville legged it to the away end and gave it the big one, and I remember saying to my dad: 'If that was Jamie Carragher doing it to the other end, I'd be made up'.

"I don't think United would have been as successful in the past 20 years, or us in the 1970s and '80s, if we didn't have this other big club at the other end of the M62."

There is solidarity between many United and Liverpool fans over many of the big issues for those who watch English football - the escalating cost of tickets, the mistrust of avaricious overseas owners.

For two sides who are unlikely to challenge for the title, there is also a sense of escape this weekend: a match when it is less about what the result does to your league standing, and all about the result itself - a one-off that could be your most enjoyable single day of the season, a chance to forget the long term and throw yourself entirely into the now.

It is one of the reasons why tickets for away fans in this contest are in greater demand than any other. Going behind enemy lines is often more of a thrill than watching your side at home. Coming away with something from a raid on your great adversaries is like nothing else.

Watching football is about the intensity of the experience: the celebration of a goal, the noise, the sense of togetherness. Never is that feeling so heightened as against your deadliest rivals.

Former United full-back Gary Neville, a staunch Mancunian, had a stormy relationship with Liverpool fans

"It will never happen, but if United were ever relegated, obviously you'd have a laugh, but I'd hate it," admits Heaton. "I wouldn't want them down."

That might surprise some outsiders. But the antipathy between the two clubs has seldom been a constant.

Where did United's great manager Sir Matt Busby ply his trade as a player? Anfield. Where did United play when they were briefly banned from Old Trafford in the early 1970s? That same stadium.

"There is a general underpinning of the rivalry by this historical non-football antipathy, and political and economic shifts much later helped to fan the flames," says John Williams, football sociologist and author of Red Men, a biography of Liverpool FC.

"But things really got moving - and became much more poisonous - in the late 1970s and early 1980s, partially for football reasons but also because of external influences."

Williams says United had the "glamour and media profile" but not the success while Liverpool fans felt the Red Devils were "media darlings who got far too much publicity" while their team were dominant.

"There was fan feuding over the roots of the new 'casual' style and Liverpool, the city, had also adapted much less well to the new economic and political realities of the 1980s," he adds. "This fuelled resentment and abuse; Manchester seemed to be doing better in recession than Merseyside.

Paul Ince celebrates scoring for Liverpool against United in 1999. He is one of only three players since the 1960s, along with Peter Beardsley and Michael Owen, to have played for both clubs' first teams

"There was a perception in Liverpool that their hugely successful but 'professional', 'workmanlike' teams were always somehow in the shadow of the stars at Old Trafford - the derisory United nickname in Liverpool at the time was The Glams.

"Because Everton and Liverpool were 'friendly' rivals - people in the same families on different sides and with no geographical territorial divide - when things properly kicked off the Reds needed a better local target than the Blues could provide."

Williams says it was "quite hard" for Merseyside football fans to generate "authentic and satisfying feelings of hatred" for the club just across Stanley Park while to United supporters, Manchester City seemed like "unlikely rivals and potential challengers".

He adds: "The bogeyman for each club seemed obvious and to lie at the opposite end of the M62: an unbearable smugness at all-conquering Liverpool, and a perceived arrogance at underachieving United.

"An FA Cup semi-final in 1985 at Goodison Park was one particular low point. Soon after, Heysel occurred and so United had their own 'Munich' with which to beat Liverpool and respond to these historic ugly chants. Escalation inevitably followed."

Eight United players were among 23 people to die after an air crash in Munich in 1958., external Twenty seven years later, 39 football fans died, external during violent clashes between Liverpool and Juventus supporters at the European Cup final at Brussels' Heysel Stadium.

With first footballing parity and then a dramatic change in the balance of power by the mid-1990s came greater tension.

Each club can now claim supremacy: United, for their 20 league titles to Liverpool's 18; Liverpool for being European champions five times to United's three.

Liverpool won the Champions League under Rafa Benitez, while United won two under Sir Alex Ferguson

As English football's appeal spread across the globe, the rivalry was given further impetus.

"That's critical, because the only two truly global clubs from the UK - even in the 23rd year of the Premier League - are Liverpool and United. Compared to other English clubs, they're way out in front," says Dr Richard Elliot, director of the Lawrie McMenemy Centre for Football Research at Southampton Solent University.

"The Premier League is a media spectacle now, and the clubs are competing for global fan bases. Fans who are detached by geography often pick teams on the basis of historical tradition and success, but inevitably they buy into those rivalries in exactly the same way as a fan who attends in person every week.

"Rivalry drives competitive sport. Some can be created by historical legacy, but media will create some too. If you can create rivalries and a sense of anticipation, you create an entertainment product that draws in a bigger audience to ensure they are consuming your product to the extent you want them to.

"The only thing that truly dictates whether the significance declines is if one of the teams is relegated. You would need a fall from grace so that one team wasn't competitive for a period of time. But even then, if they came together in a cup competition, I still think the rivalry would be as intense as it is now."

Sunday may not be the spiciest instalment of this long-running drama. The exits of Sir Alex Ferguson - Liverpool always his target, always his benchmark - and Rafa Benitez ("I want to talk about facts"),, external as well as Luis Suarez and Patrice Evra, have diluted some of the kick that was there over the past decade.

But it remains a game like no other, and both clubs and supporters should cherish it.

- Published11 December 2014

- Published16 March 2014

- Published24 March 2014

- Published16 March 2014

- Published16 March 2014